In the early 1900s, many hard-working sailing vessels saw out their days plying the waters between Australia and the islands of the South Pacific. Few, however, would have had such a fascinating history as that of the Norna.

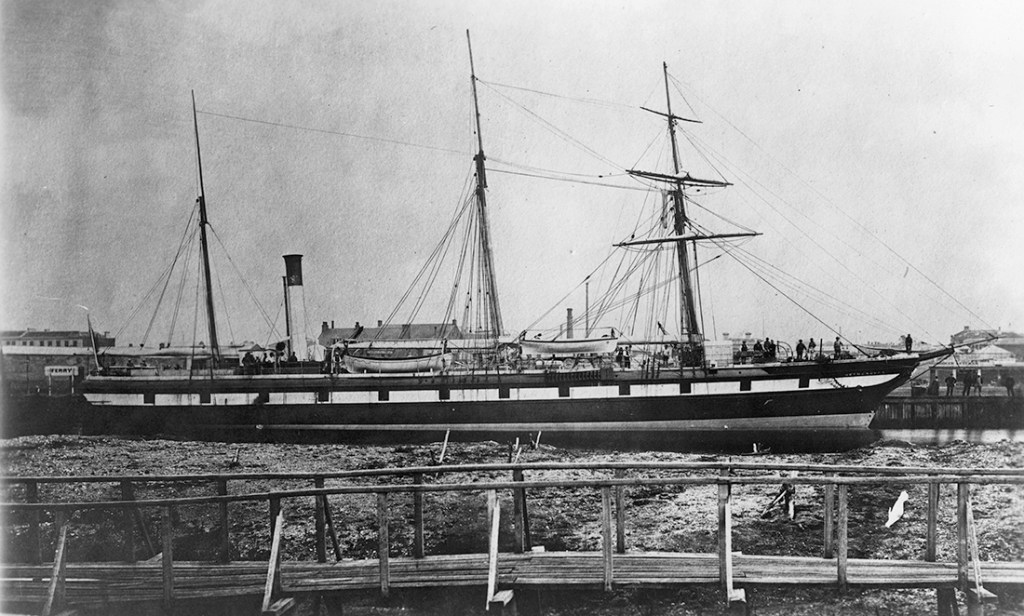

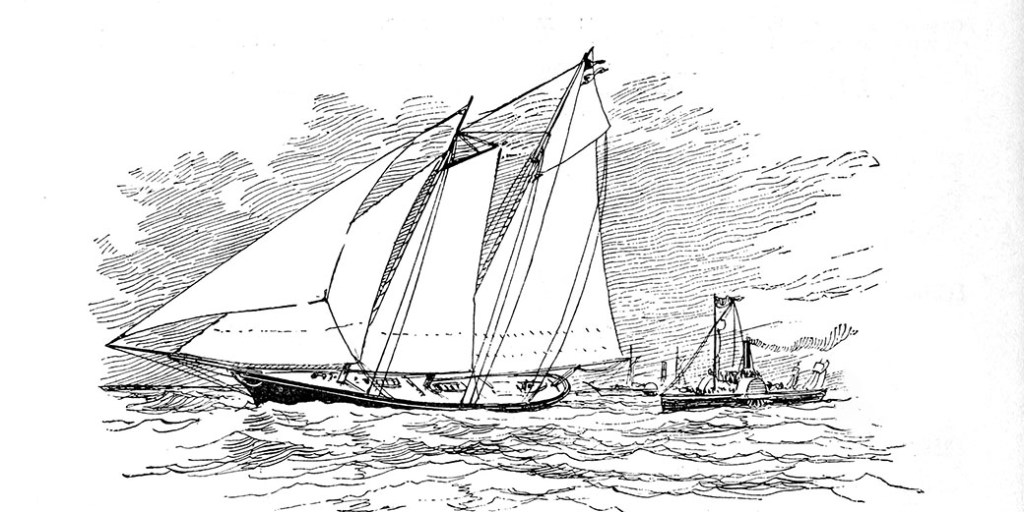

The Norna was built in New York in 1879 as a luxury ocean-going schooner rigged yacht. She was lavishly fitted out and built to be a fleet-footed racer. For the next decade or more, she held her own in many long-distance ocean races.

Then, in 1895, she was purchased by self-styled “Commander” Nicholas Weaver, who claimed to represent a Boston newspaper empire seeking to establish a presence in New York. He was, in fact, a brazen conman.

A few years earlier, Weaver had fallen foul of the law and only escaped gaol by testifying against his partner. He then hustled himself off to the West Coast, where he no doubt perfected his craft.

Now back in New York, he planned to take the Norna on a round-the-world cruise, sending back stories of his adventures which would be syndicated in America’s Sunday newspapers. He found several financial backers willing to cover his expenses in exchange for a share of the syndication fees. They founded a company, and Weaver sailed for the warm climes of the Caribbean.

There, he made himself a favourite among the members of the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club, representing himself as the “Acting Commodore” of the prestigious Atlantic Yacht Club. The good people of Bermuda were not necessarily any more gullible than anyone else whom Weaver had separated from their money. But when someone sails into harbour aboard a 115-foot luxury yacht with a sailing crew of ten plus a cook and steward, few questions are likely to be raised. It also helped that Weaver himself was handsome, self-assured, and very charismatic.

Weaver lived life to the full and spared himself no expense. He began hosting poker parties on his yacht, inviting only Bermuda’s most well-heeled residents. Though he proved to be uncannily lucky at cards, the winnings could not have covered his expenses. He funded his lavish lifestyle by chalking up credit with local merchants where possible, passing dud cheques if necessary, or forwarding invoices to his financial backers in New York.

However, it was only a matter of time before things began to unravel. But before the inevitable day of reckoning, Bermudans awoke one fine morning to find the Norna and its flamboyant owner had cleared out in the dead of night.

Weavers’ backers eventually realised they had been scammed and that they would never recoup their money. They wound up the company and stopped sending him money. But that did not deter Weaver from continuing on his round-the-world cruise.

He visited many ports over the next couple of years, where he dazzled the wealthy with his largesse, while taking them to the cleaners at the poker table. He cruised around the Mediterranean, stopping long enough to run his con but always skipping out before debts became due.

At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, in April 1898, he and his American-flagged Norna found themselves in hostile waters. Realising his yacht might be seized, he set sail at his best speed with the Spanish navy in hot pursuit. Despite Weaver’s many character flaws, he was a superb mariner. Thanks to his skill and the luxury yacht’s fast sailing lines, the Norna outpaced the Spaniards, crossing into the safe waters of British-owned Gibraltar. There, he repaid his welcome by passing a fraudulent cheque for $5,000 and was once again on his way.

During his travels around Europe, Weaver made the acquaintance of a man named Petersen, a fellow grifter. Together, they would prove a formidable team.

Weaver and Pedersen would arrive in a new city independently, only to be introduced to one another by someone local, or they would fabricate a chance meeting as if they were strangers. Regardless of how they met, the result was always the same. They would get a high-stakes poker game going where one or the other would clean up.

When Weaver reached Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), he was introduced to Petersen, who just happened to have recently arrived by steamer. They quickly got to work separating the wealthy from their wealth before moving on again. The pair repeated the same stunt in Sumatra, in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), as well as in Hong Kong and Yokohama, Japan. At each port, they fleeced the local high society and vanished before alarm bells rang. In Yokohama, Weaver passed himself off as the commodore of the New York Yacht Club and flew its pennant from his vessel. Weaver and Pedersen befriended each other and enjoyed many an evening with others playing poker on the Norna. Then, one morning, the yacht was gone. Pedersen joined the chorus baying for Weaver’s blood, claiming he, too, had been taken for a fortune. He then quietly slipped away on the next steamer leaving port.

From Yokohama, the Norna made its way to Honolulu, where Weaver and Petersen briefly reunited. But when Weaver left Hawaii, Petersen remained. It seems as though the partnership had come to an end. The Norna stopped at Samoa long enough for Weaver to fleece the locals, then sailed on to New Zealand. At Auckland, Weaver began his now well-honed con, though this time without the able assistance of Petersen.

Weaver racked up considerable debts, but before he could make his departure, the Norna was seized as surety. Realising the game was up, Weaver caught the next steamer bound for Sydney, vowing he would return to Auckland with the necessary funds to have his beloved yacht released. Not surprisingly, he vanished, and the yacht was put up for sale. It was purchased by a Sydney merchant and brought across the Tasman in June 1900.

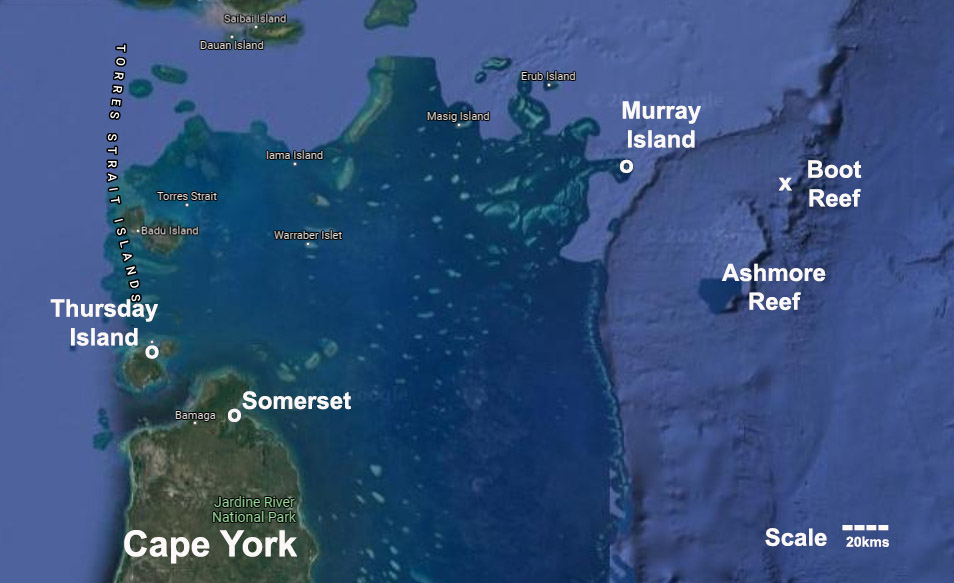

The Norna was stripped of her luxurious fittings, and the cabins were removed to make way for a spacious hold more fitting for her new working life. The Norna passed through several hands over the next 13 years. She served as a pearling lugger in Torres Strait and a trading vessel among the Pacific Islands. One owner even used her to salvage copper and other valuables from old shipwrecks far out in the Coral Sea. But, in June 1913, she, herself, was wrecked on Masthead Reef 50 km northeast of Gladstone Harbour. So ended the Norna’s fascinating and colourful career.

© Copyright Tales from the Quarterdeck / C.J. Ison, 2022.

To be notified of future blog posts, enter your email address below.