Some people might be surprised to learn that the oldest recorded shipwreck off the Australian coast dates back to 1622. That predates Cook’s voyage up the east coast by 148 years. It occurred 20 years before Abel Tasman partially circumnavigated the island of Tasmania. Or just six years after the Dutch navigator Dirk Hartog nailed a pewter plate to a post near Shark Bay, recording his discovery of a big lump of land that had until then been unknown to anyone but its inhabitants.

The Tryall* was a 500-ton East India Company merchant ship launched in 1621. Her maiden voyage was meant to take her from England to the East Indies to deliver cargo before returning home with her hold filled with spices. The East India Company chose a master mariner named John Brooke to command the vessel on this most important voyage.

The Tryall departed from Plymouth on 4 September 1621 with a crew of about 140 men. Captain Brooke sailed down the west coast of Africa and pulled into Table Bay for water and fresh supplies. While there, he learned that a new route across the Indian Ocean had been established, cutting the sailing time to Batavia by several months. The traditional route to the East Indies had ships follow the coast around Africa’s southern tip, then pass through the Mozambique Channel. Once north of Madagascar, they would venture out into the Indian Ocean. The new “Brouwer Route,” as it was called, took full advantage of the roaring forties, which swirled around the bottom of the world unimpeded by any significant land mass. Captain Brooke received orders to take the Tryall below 35 degrees South and use the Brouwer Route. Brooke tried to hire a sailing master for this leg of the voyage, for neither he nor anyone else on the ship had sailed the southern route before. He was unable to recruit anyone, so on 19 March 1622, Captain Brooke sailed the Tryall out of Table Bay and into the unknown. Six weeks later, they were off the coast of Western Australia.

Brooke likely sighted land in the vicinity of Point Cloates around 22.7 S 113.6 E, mistaking it for Barrow Island about 200 km further north. It would appear that he had underestimated the strength of the roaring forties and had been blown too far east before he turned his ship north, something easily done with the rudimentary navigation instruments of the day. But it was an error he would never admit to having made.

For the next couple of weeks, the Tryall struggled to make progress against fresh northerly winds, but when the wind swung around to the south again, they got underway. Then, on the night of 25 May 1622, disaster struck.

The Tryall slammed into submerged rocks near the Montebello Islands. Stuck fast on the reef and being smashed by powerful swells, the Tryall began to break apart. Brooke and a handful of men, including his son, managed to get a small skiff over the side and escaped the doomed ship, apparently leaving everyone else to their fate. Soon after, some of the crew were able to launch the ship’s longboat, and 35 sailors clambered aboard and got clear of the Tryall. They landed on one of the Montebello Islands, where they remained for about a week, preparing the boat for the 2,000 km-long voyage to Batavia. Ninety-three men lost their lives. Captain Brooke reached Batavia on 5 July, where he penned a letter to the ship’s owners reporting the ship’s loss. In it, he claimed that he had followed the proscribed route precisely, but had struck a reef not laid down on his chart. Brooke probably thought that they were the only survivors, and his version of events would go unchallenged. His letter, he hoped, would absolve him of any blame for the loss of the ship, its valuable cargo, and so many lives.

When the longboat finally made it to Batavia, those survivors had a very different story to tell. One of them, a trader named Thomas Bright, wrote his own scathing letter to London condemning Captain Brooke. Bright blamed the wreck on Brooke’s poor navigation that had brought them so close to New Holland and the fact that he had not posted a lookout despite knowing he was in those dangerous waters. He also claimed that Brooke had abandoned the wreck as quickly as he could in the partially filled skiff, leaving the rest of the men to their fate.

In his report to the ship’s owners, Brooke had also recorded that the wreck site was much further west than where it had occurred to mask his error in navigation. For the next three centuries, the non-existent rocks caused some confusion and uncertainty among navigators sailing those waters. It was not until 1936 that the historian Ida Lee established that the wreck site was likely to be off the northwest of the Montebello Islands. Then, in 1969, amateur scuba divers found the wreck site where Lee had said it would be.

* Tryall is also seen spelled as Tryal and Trial.

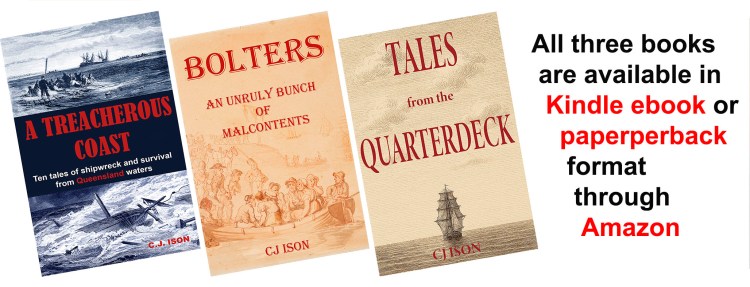

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022 (Updated 2025).

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.

Leave a reply to Dix épaves historiques moins connues mais remarquables – Blog Voyage Cancel reply