As the Endeavour famously made its way up Australia’s east coast in 1770, there was a moment when the success of Cook’s voyage hinged on a pile of sticky animal dung, and some handfuls of wool and rope fibre. The incident occurred shortly after passing Cape Tribulation, so named by Cook because that was where his troubles began.

All of Monday, 11 June, the Endeavour had been sailing about 15 kilometres off the coast, pushed along by an east-southeasterly breeze. At 6 in the evening, Cook ordered the sail to be shortened, and he instructed the helmsman to steer to the seaward of two small islands lying directly in their path. He also had a seaman in the bow constantly sounding the depth, for he was literally sailing into the unknown. Then, shortly after 9 o’clock, as he and his officers sat down to supper, the seabed suddenly rose to within 15 metres of the sea’s surface. Cook called the crew to their stations and was prepared to drop anchor or adjust sail, but as suddenly as the seabed had risen, it dropped away again. They had just passed over a coral reef.

Then, an hour or so later, the Endeavour ran up on a coral reef and stuck fast. Cook was about to discover he had stumbled into a dangerous labyrinth of reefs and shoals where the Great Barrier Reef pinched in close to the Australian mainland.

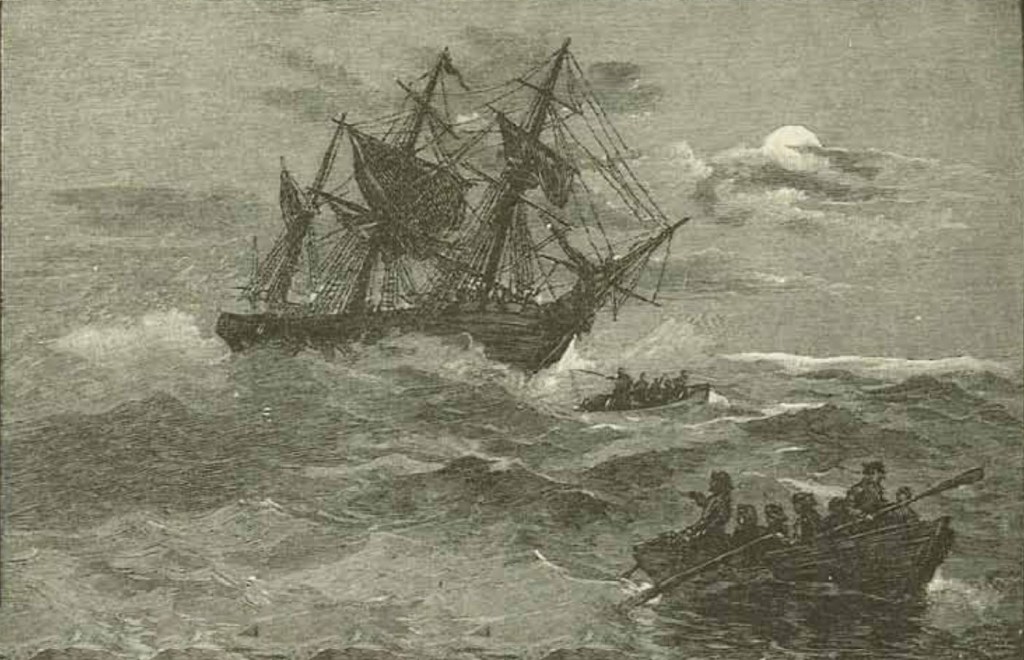

An anchor was taken out aft in the hope that they might be able to kedge the Endeavour back off the reef on the high tide. But when the time came for the men to heave, she would not budge. The next high tide would be at 11 a.m., so he ordered the crew to lighten the ship for the next attempt. Cannons, ballast, water casks, stores of all sorts were tossed over the side. At high tide, they tried kedging off the reef a second time, but again she would not budge. Yet more stores went over the side, and on the third attempt, the Endeavour floated free, but the hull had been breached, and water was pouring into the hold.

All three working bilge pumps were manned non-stop to stop the Endeavour from sinking. Everyone, sailors, officers, civilian scientists, and even Cook himself, took fifteen-minute turns at the pumps. Cook knew their survival hinged on finding a suitable place to beach the stricken vessel so they could make repairs. But there was no guarantee he would find such a place before his ship foundered.

Then, a young midshipman, Jonathan Monkhouse, suggested fothering as a means of plugging the leak and buying them some much-needed time. He had seen it done with great effect on a ship he had previously served on. With nothing to lose, Cook set him to work, aided by as many men as he could spare from pumping and sailing duties.

Monkhouse took a spare canvas sail and spread it out on the deck. He gathered up a large quantity of rope fibre and wool and had his men chop it up finely. The short fibres were mixed with dung from the animal pens and formed fist-sized sticky balls of odorous matting. These were slopped onto the sail about six to eight centimetres apart until a sizeable portion of the canvas had been covered.

The sail was then lowered over the side of the ship forward of the hole in the hull, and then drawn back along the side. As the fother – the particles of oakum and wool – were sucked in through the rents in the hull, they caught on the edges, and in no time at all, they plugged the holes and slowed the leaks to a trickle.

“In about half an hour, to our great surprise, the ship was pumped dry, and upon letting the pumps stand, she was found to make very little water, so much beyond our most sanguine expectations had this singular expedient succeeded,” Joseph Banks would later write in his journal.

For the first time since striking the reef, the Endeavour was out of immediate danger. She was now taking on less than half a metre of water each hour, and that could be easily managed using just a single bilge pump.

The Endeavour sailed a bit further up the coast until they reached what is now named Endeavour River. There, Cook found a steeply sloping sandy beach ideally suited to careening his ship. And, after several days’ delay waiting for safe conditions to enter the river mouth, he ran the barque onto the beach to examine the damage.

At 2 a.m. [on 23 June] the tide left her, which gave us an opportunity to examine the leak, … the rocks had made their way [through] 4 planks, quite to, and even into the timbers, and wounded 3 more. The manner these planks were damaged – or cut out, as I may say – is hardly credible; scarce a splinter was to be seen, but the whole was cut away as if it had been done by the hands of man with a blunt-edged tool,” Lieutenant James Cook later wrote.

Cook also found a fist-sized lump of coral lodged in the hull, along with pieces of matted wool and oakum, which so successfully stemmed the leak.

At low tide the next day, the ship’s carpenters began replacing the damaged planks and the armourers got the forge going to manufacture replacement bolts and nails to secure the new timbers in place. In all, Cook and his crew spent six weeks there making repairs and re-provisioning.

Once the hull was repaired, the Endeavour put back out to sea on 4 August and gingerly made her way north. But they were still trapped in the same dangerous stretch of water that had come so close to ending the voyage. It would take several days of careful and nerve-wracking sailing before they escaped the intricate maze of coral shoals.

The full story of the Endeavour’s stranding on the Great Barrier Reef is told in A Treacherous Coast: Ten Tales of Shipwreck and Survival from Queensland Waters.

© Copyright C.J. Ison, Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

Enter your email address below to be notified of new posts.

Leave a comment