Before the German Cruiser Emden was engaged by HMAS Sydney, a fifty-strong party was sent ashore at Cocos Island to destroy the telegraph station linking Australia to South Africa. As the two ships exchanged shells in a battle that lasted ten hours, the shore party could do little but watch on and hope for the best.

On 9 November 1914 Lt von Mucke had been ordered to lead a party ashore to disable the cable station on Cocos Island. But shortly after the Germans had disabled the station and rounded up the telegraph operators, the Emden signalled for them to return to the ship. Then von Mucke saw the Emden raise its battle flag and fire a salvo at a target then hidden from his sight.

The Emden then steamed off leaving the shore party stranded on the island. They had no chance of catching up to the fast-moving cruiser then fighting for its life. As the Emden continued to engage HMAS Sydney, von Mucke immediately declared Martial Law over the island and deployed his four machine guns and 30 or so sailors to defend against any landing.

At one time German sailors and Australian telegraph operators stood together watching the naval battle play out in front of them. But eventually, the two ships disappeared over the horizon, the Emden clearly the worse for the ongoing encounter.

Von Mucke held out little hope that his ship would return for them victorious. The mortally damaged Emden was deliberately run aground the next day and the survivors surrendered to HMAS Sydney. Von Mucke also realised that he and his men would eventually have no choice but to surrender should they remain on the island. He decided to leave while they still could, seizing the schooner Ayesha.

The three-masted schooner was the property of John Clunies-Ross, who also happened to own the Cocos Islands themselves. His Great Grandfather had claimed the uninhabited islands in the 1820s and began a coconut plantation using workers brought from Malaya.

Von Mucke requisitioned provisions to last his men 8 weeks at sea and had them loaded onboard. The departure had an oddly festive quality to it. Residents asked for autographs from the Germans, and also had them pose for photographs. Then, as the sun set in the west, von Mucke bid the residents “auf wiedersehen” and sailed out of the harbour to three resounding cheers.

Before leaving he hinted they were bound for East Africa to throw any pursuers off his scent. However, his real intention was to head north to the Dutch port of Padang on the island of Sumatra. Von Mucke and his men arrived at Padang on 26 November after 17 days sailing. There, he hoped to get help from any German ships in port while he planned the next leg of his return to Germany. While the Dutch were neutral during the First World War, that meant they would neither hinder nor aid any of the combatants. “The master of the port declined to let us have, not only charts, but also clothing and toothbrushes,” as he rigorously enforced the port’s neutrality, von Mucke later lamented. The Dutch authorities asked von Mucke and his men to surrender themselves to internment but the German officer declined and 24 hours later they left the harbour.

For two weeks they remained close to the Sumatran coast hoping to cross paths with a German ship while avoiding Allied naval vessels patrolling those waters. Their luck held out and on 16 December the German merchant ship Choising, which had been undergoing repairs at Padang, came into sight.

Von Mucke and his men transferred onto the ship and with heavy hearts, they scuttled the schooner which had been their home for the past six weeks. The Choising to the port of Al Hudaydah in the Red Sea. From there the men made their way to Damascus and then on to Constantinople in Turkey. Von Mucke finally reported to the German Embassy there on 9 May 1915. For his efforts, he was awarded an Iron Cross.

Source: The Story of the Great War, Vol III, Chapter 31, “Story of the Emden.”

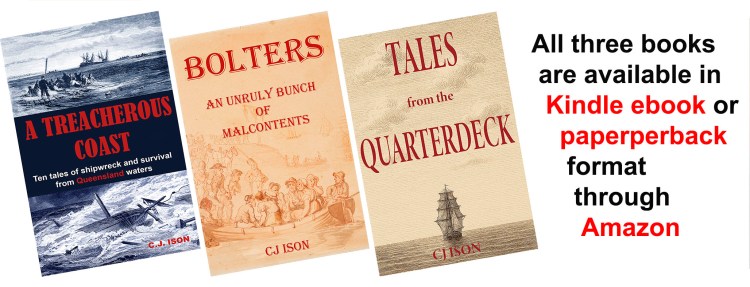

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.