Robert Stewart was not your typical convict born into England’s poverty-stricken underclass and sentenced to transportation for committing some petty crime. Rather, he came from a comfortable though modest middle-class family. Born in 1771, the first ten years of his life would have likely been idyllic, but then his father died, and a year later, his widowed mother enrolled him into the Royal Mathematical Institution. There, he joined the ranks of boys learning maths and celestial navigation, preparing them for apprenticeships in the merchant marine or Royal Navy. Had he graduated, Stewart would have had a respectable and rewarding career that would one day see him master of his own ship. However, Stewart harboured ambitions of one day enjoying the sort of wealth and privileges that “higher-born” gentlemen took for granted.

In June 1785, Robert Stewart’s rebellious nature and frequent absences led to his expulsion from the institute. He then joined the Royal Navy as an ordinary seaman and over the next 12 years rose to the rank of Petty Officer. But in 1798, aged 27, he deserted, likely embittered that he would never be promoted into the officer ranks. Three years later, he stood trial on fraud and forgery charges. Stewart had purchased goods while posing as a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy and paid for them with a forged cheque. Caught, charged and found guilty, he was sentenced to transportation for life and sent to Van Diemen’s Land.

Stewart arrived in Hobart on the Calcutta in 1803 and did not attract any undue attention for a year or so. However, twice, he attempted to escape by seizing small colonial vessels and setting sail. Both times ended in dismal failure, and he was returned to Hobart to face punishment. After his second attempt, he was sentenced to death. Stewart was only spared that punishment due to a blanket pardon given to all prisoners under capital sentence by the recently appointed Governor of NSW, William Bligh. However, in 1808, he was sent to Sydney to serve a period of time at hard labour.

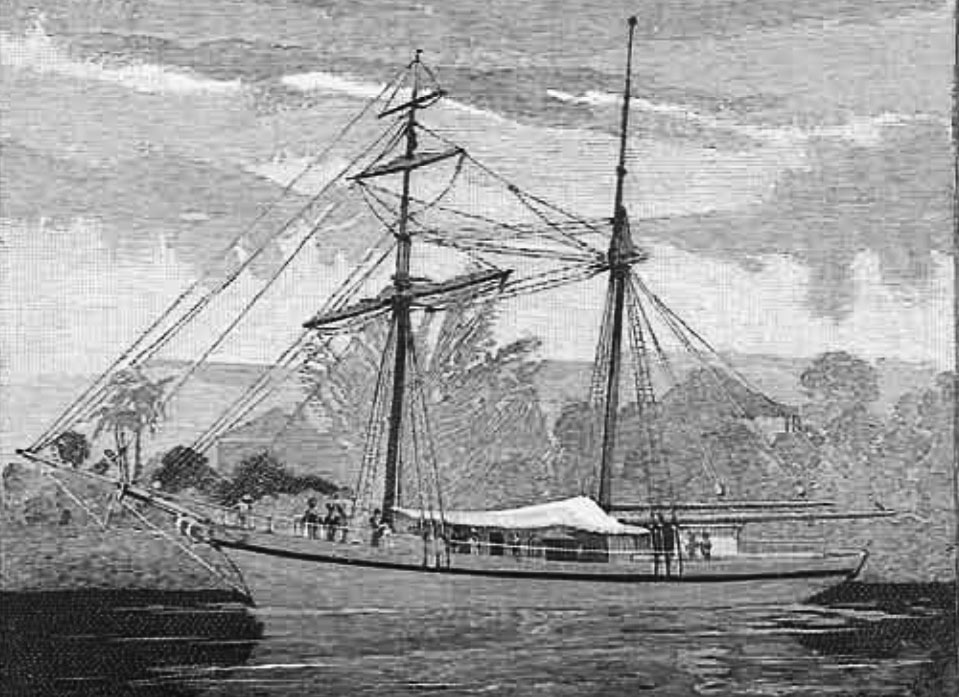

But Stewart never gave up hope of regaining his freedom. This time, he had his eye on the 180-ton brig Harrington anchored in Sydney Cove. She had recently returned to Port Jackson from China with her hold filled with tea after delivering a cargo of Fijian sandalwood. So lucrative was the trade that the Harrington’s captain was set to do it again. The ship was stocked with enough supplies to last the crew several months and was to sail any day.

At 10 o’clock on the night of 15 May 1808, Stewart led as many as 30 fellow convicts out to the waiting ship in two boats they had just stolen. They came alongside as quietly as they could so as not to alert any sentries. But when Stewart climbed over the side, he found he had the deck to himself. The rest of the men swarmed over the gunwales. Some went forward to secure the crew. Others went aft to take care of the officers. The Harrington’s Chief Officer, Arnold Fisk, woke to the sight of Stewart holding a pistol to his head. The brig’s captain and owner could not be found, for he had gone ashore earlier that day. As Stewart and his men took control of the ship, the captain was blissfully asleep in his home overlooking Sydney Harbour.

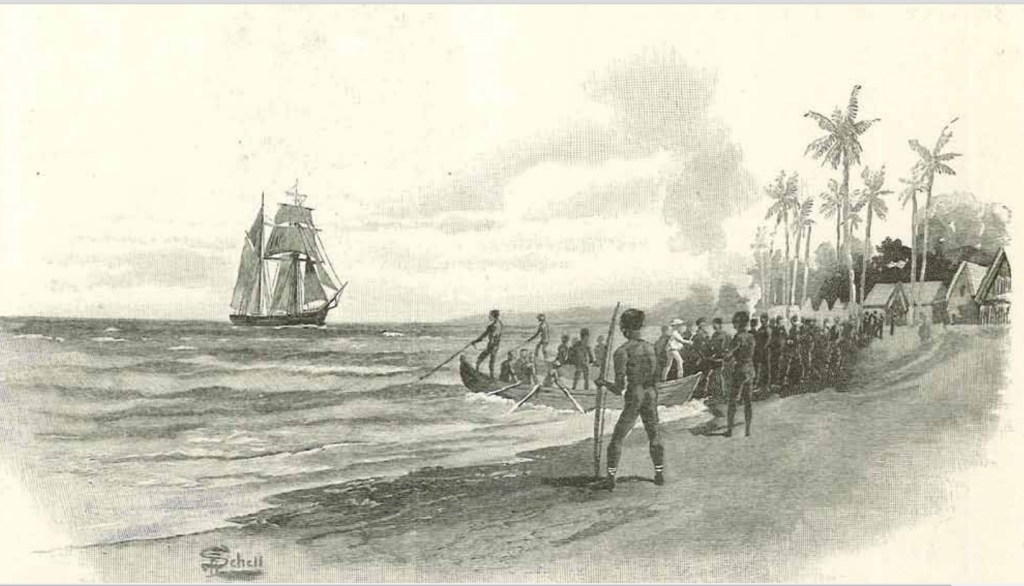

With the ship’s company under guard, the convicts cut away the anchors and used the two stolen boats to tow the Harrington the length of Sydney Harbour. Once they reached the Heads, the sails were unfurled and the wind took them out to sea. By 7 a.m., they were about 20 nautical miles (40 kilometres) off the coast.

Stewart ordered the Harrington’s crew into the two boats so they could make their way back to Sydney. They pulled into Sydney Cove later that afternoon to learn the alarm had already been raised. Earlier that morning, Captain Campbell had looked out across the Harbour to find his ship was not there.

It took authorities three days to organise a ship, the Pegasus, to go in pursuit. By then, Stewart and the Harrington were long gone. The Pegasus cruised the Fijian Islands and then sailed on to Tonga before returning to Sydney via New Caledonia. She was gone nine weeks and arrived back empty-handed. For a time, it looked as if Robert Stewart and his band of bolters had made good their escape. Stewart had sailed the brig nearly 8000 kilometres north and was approaching Manila in the Philippines when their luck ran out. HMS Dedaigneuse spotted the unfamiliar vessel, and her captain sent a boarding party across to investigate. By then, the Harrington was flying American colours, and Stewart presented the officer with papers purporting that the ship was of American origin. The forged documents did not fool the officer in charge of the boarding party who seized the ship. Stewart, now calling himself Robert Bruce Keith Stuart, was taken back to the Dedaigneuse while the rest of the convicts were locked in the Harrington’s hold, now under the command of a British naval officer and a prize crew.

Shortly thereafter, the Harrington ran aground off the island of Luzon. Most of the convicts were reported to have got ashore where they fled on foot. However, there is some evidence to suggest that their “escape” might have been fabricated, and they were actually press-ganged into Royal Navy service.

Stewart, on the other hand, had a much easier time of it. He spoke and carried himself in a gentleman-like manner, professed to have enjoyed a liberal education and that he had connections to some of Britain’s most prestigious families. Stewart claimed to have once been a lieutenant in the Royal Navy before he fell victim to the penal system. As a result, he was accorded considerable leniency by the Dedaigneuse’s captain. Captain Dawson allowed Stewart “every reasonable indulgence and forbade to place him under personal restraint.” That was until Stewart tried to escape and came very close to succeeding. After that, he was placed under close confinement. Stewart was eventually delivered to British officials in India, where he continued masquerading as a gentleman in need of help rather than the escaped convict that he was.

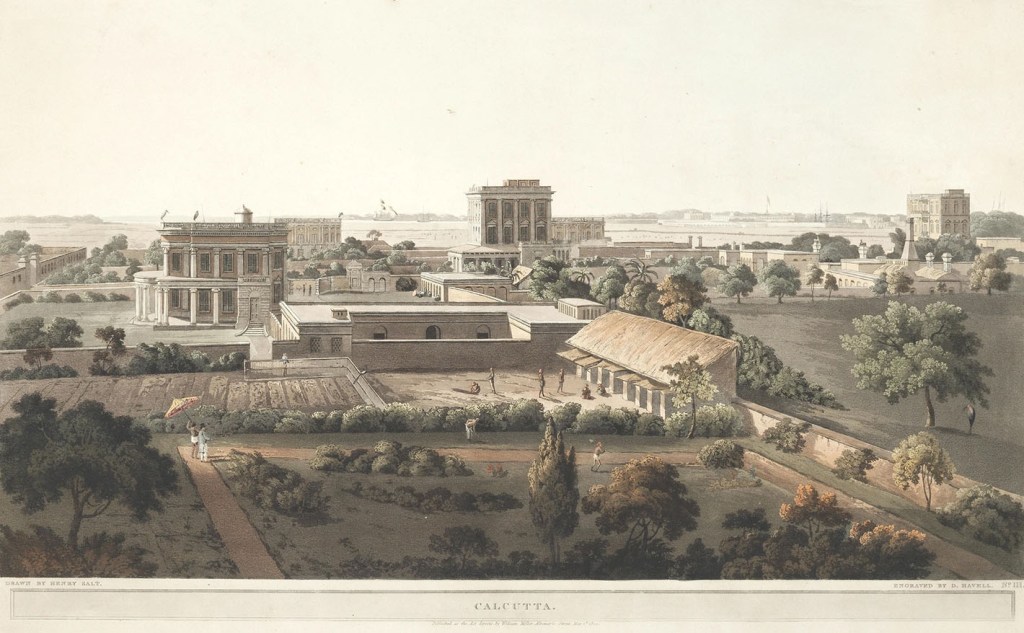

He knew he could not hide the fact that he had committed an offence serious enough to warrant transportation to New South Wales. So, instead, he fabricated a preposterous story about his conviction. Stewart claimed he had eloped with a young lady from a very respectable family, though chivalry required him to leave her unnamed. But, after they were secretly wed, a junior Baronet who also had desires for the lady broke into their apartment. Stewart said he had shot and injured the young aristocrat in what he described as an affair of honour. Stewart said he had been unfairly found guilty of attempted murder and sent to New South Wales. That sounded more in keeping with a gentleman than being caught for the more tawdry crime of passing a forged cheque. His tale garnered much sympathy from the colonial administrators in Calcutta. The Chief Magistrate even went as far as to champion Stewart’s cause, penning a letter to his superior suggesting he should be released.

But then, in August 1809, Stewart’s time ran out. The British officials could not ignore that he was a fugitive from justice, and the Governor General ordered him to be returned to Sydney. He was placed on board a ship bound for Australia, but before it sailed, Stewart went missing. At first, the captain claimed he had jumped overboard and likely drowned, but it later transpired he had been whisked away in a boat by one of his many admirers and taken back to Calcutta.

So, Robert Stewart may have escaped justice and settled in India under yet another assumed name, or caught the next ship leaving port. No one knows for the trail grows cold then. One thing is certain: he never returned to New South Wales to serve out his sentence. Nor did he face punishment for masterminding the seizure of the brig Harrington.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.