Between 1788 and 1868, more than 162,000 convicts were loaded onto transport ships and banished to the colonies to serve out their sentences. Such were the living conditions onboard some of these vessels, coupled with the hazards of sailing such vast distances in isolated waters, perhaps as many as one in one hundred perished before ever setting foot on Australian soil. When the Neva struck a reef in Bass Strait, of her 226 casualties, nearly 150 of them were convicts.

The 337-ton barque Neva set sail from the Irish port of Cork on 8 January 1835, bound for Sydney, New South Wales. On board were 153 female prisoners of the crown, 55 children and nine free female emigrants. The crew, under the command of Captain Benjamin H. Peck, numbered 26. During the passage, three people died and one baby was born, so by the time they were nearing their destination, the ship’s complement numbered 241, passengers and crew.

By 12 May, the Neva had rounded the Cape of Good Hope, stopped briefly at the island of St Paul for fresh supplies and was about to enter Bass Strait. At noon, Captain Peck calculated they were about 90nm (170 km) west of King Island. As daylight faded into night, he posted a lookout to warn of any dangers lying in their path. He would remain on deck through the night, but for a two-hour break, as his ship negotiated that dangerous stretch of water.

A stiff breeze was blowing, and the ship was being pushed along under double-reefed topsails. Around 2 o’clock in the morning, the lookout sighted the dark silhouette of land against the lighter night sky in the distance. Peck ordered the course altered a little to the north to ensure he safely cleared King Island. Then, about two or three hours later, the frantic call came from the lookout, “breakers ahead,” as a line of white water emerged from the pre-dawn gloom.

Captain Peck immediately gave the order to tack, but it came too late. As the Neva was turning into the wind, she struck a rock and lost her rudder. With the wheel spinning freely, the stricken ship was now at the mercy of the wind and current. They had likely struck Navarine Reef about three kilometres northeast of Cape Wickham, the northernmost point of King Island.

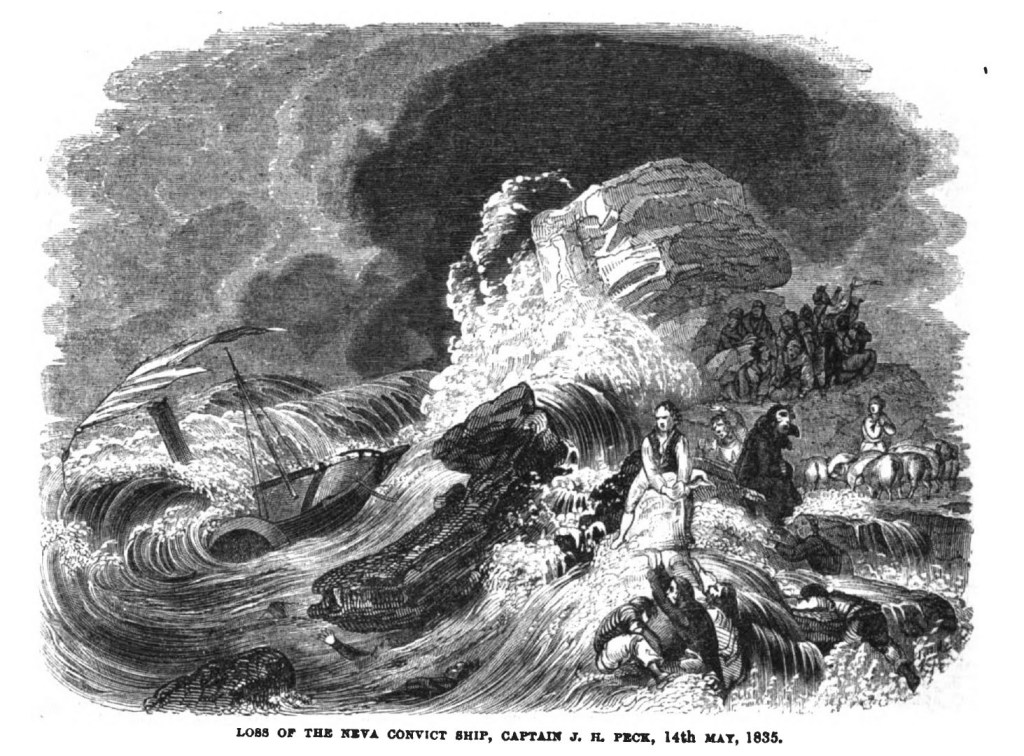

Suddenly, the Neva struck hard a second time. She hit on her port bow and swung broadside against the reef and immediately started taking on water. Below decks, the prison cages collapsed under the violent force of the collision, and the terrified female convicts rushed on deck.

The gig, one of the four available lifeboats, was lost as it was being lowered into the water. Captain Peck then ordered the pinnace over the side, and he, the ship’s surgeon, several sailors and some of the female passengers climbed in. But before they could put away, it was overwhelmed by a deluge of terrified women, frantically trying to escape the ship. The boat sank under their weight, and everyone was spilled into the churning water. Only Peck and the two seamen made it back to the ship alive.

The captain then set about launching the longboat. However, this time, as he boarded, he made sure his panicking passengers were kept at bay. But this time, as soon as the boat was lowered, it was swamped by the surging seas crashing around the ship. Everyone was tossed into the water. Only Captain Peck and his first mate made it back to the ship this time.

After the loss of three boats, the cutter was their only remaining lifeboat. It is not clear from reading survivor accounts why it was never launched. Considering the sea conditions it would likely have met with the same fate as the longboat. The most likely reason the cutter was never launched is that the Neva began to break up before it could be lowered.

Part of the deck sprang away from the superstructure and then split in half, effectively forming two rafts. Captain Peck, some of the crew and several women made it onto one of them while the first mate and several other people were lucky enough to find themselves on the second. The two rafts drifted clear of the wreckage, leaving the remaining convict women clinging to those parts of the ship still jutting out of the surging seas.

The rafts and several other pieces of wreckage with people clinging to them drifted with the currents for several hours before they came to ground in a sandy bay at the northern end of King Island. The mate’s raft rode the surf in and washed up high on the beach, and most of the people who had clung to it survived.

The captain’s raft was not so lucky. The timber platform had come away with a large section of the foremast protruding below the surface. As they entered the shallows, the mast caught on the bottom some distance from the beach. Waves swept everyone from the raft, drowning anyone who could not swim. Only the captain, a seaman and one woman made it through the pounding surf to reach shore alive.

Twenty-two people made it onto King Island, but seven of them died within 24 hours either from exposure or from injuries sustained during their escape from the wreck. The remaining 15 survivors used sails and spars washed ashore to build makeshift shelters, and then they began collecting what provisions had been washed ashore. Over 100 bodies were found scattered among the debris, and they were buried in several mass graves in the coming days.

Having resigned to waiting it out until they could be rescued by the next passing ship, Peck and the others began foraging for food to supplement the provisions that had washed ashore from the Neva. But unbeknown to them, there was another party of castaways on King Island. They had been shipwrecked earlier on the south-eastern end of King Island and had come to investigate when they saw wreckage drifting down the coast. They eventually came upon the Neva survivors. A short time later all the survivors were discovered by a sealer and his Aboriginal wife who lived permanently on the island. They cared for the castaways until help finally arrived.

After being marooned for a month, the castaways were found by Charles Friend, the master of the schooner Sarah Ann. He had touched at King Island on his way back to Launceston after delivering provisions to a whaling station elsewhere in Bass Strait. He took off all the survivors except two of the Neva’s sailors and a convict woman, who had been out foraging for food at the time. Unable to find a safe place to anchor, he was not prepared to risk losing his ship waiting for them to return.

The Sarah Ann reached Launceston on 27 June, and a cutter was immediately dispatched to King Island to collect the remaining three castaways. In all, just fifteen of the 241 passengers and crew survived, making it one of Australia’s worst maritime disasters.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2023.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.

Leave a comment