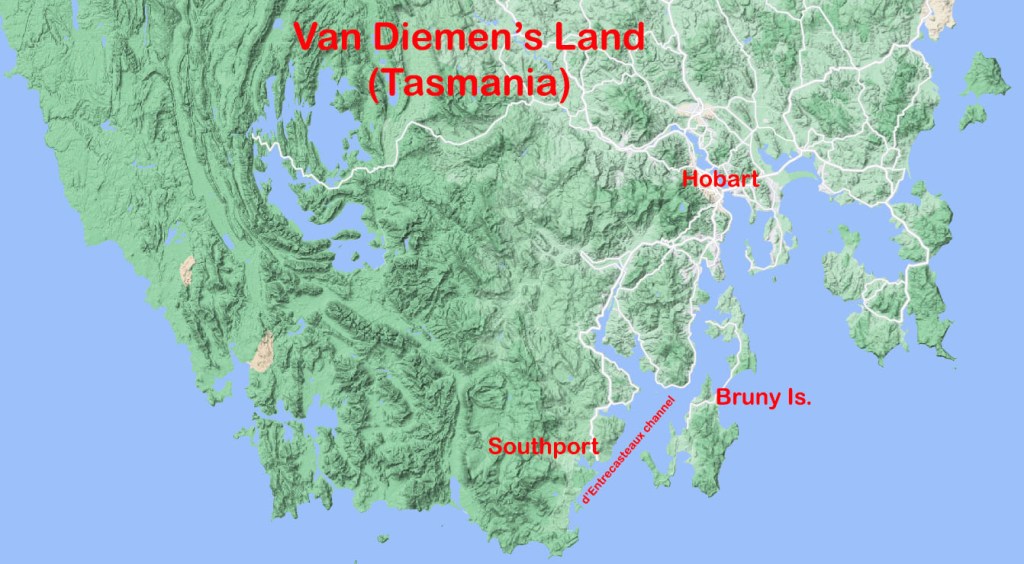

The 400-ton ship George III sailed from England on 12 December 1834, bound for Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). She was carrying nearly 300 people, of whom 220 were convicts. When they were less than 80 km from Hobart, tragedy struck with a terrible loss of life.

Around 11 a.m. on Sunday, 12 April 1835, the George III made land at South Cape, the southernmost point of Tasmania. By early evening, they had entered the D’entrecasteaux Channel to make the final run up the coast to the mouth of the Derwent River. From there, it would have been a short cruise up the river to Hobart Town. She put the dangerous Actaeon Islands behind her around 8.30 that night. The moon was out, the weather mild, and they were being pushed along at a modest 1 ½ to 2 knots (3 – 4 km/h) by a light breeze blowing off the land.

Captain William Moxey had a man in the chains sounding the passage as they made their way north. Repeated soundings showed they were in 20 fathoms (36m) of water, which was more than deep enough for safe passage. Then, shortly before nine o’clock, Moxey was stunned to hear the man call out “quarter less four,” meaning they were in less than four fathoms (7m) of water. He ordered the helm put hard to port. But before the ship could respond, she struck ground and came to a stop where the chart said there was clear passage.

The captain had soundings taken around the ship and found they were stranded on an uncharted rock with between three and five metres of water surrounding them. The initial collision was not particularly violent, but now that the ship was stuck fast, the ocean swells began lifting her up and dropping her back down on her rocky perch. Within minutes, the repeated pounding brought the main mast crashing down. The mizzen mast came down with it, littering the deck with a tangle of rope, canvas and timber spars.

The crash brought everyone on deck, except for the prisoners. Seamen not on watch, passengers and the complement of soldiers hastily dressed and came up to see what had happened. Captain Moxey gave the order to abandon ship and oversaw the evacuation in the ship’s boats. However, efforts were severely hampered by the continued pounding and the mess of debris strewn across the deck and floating in the water.

Moxley ordered one of his boats with a crew of seven to make for Hobart as quickly as possible to get help. Then he got the evacuation of the passengers and the rest of the crew underway. Meanwhile, the convicts were still locked below deck with armed guards stationed over the hatchway.

The situation was becoming dire for the convicts trapped in their prison. They were already standing waist-deep in freezing water, and despite their pleas to the guards to be let out, the hatch covers remained locked. In genuine fear for their lives, several rushed forward and tried to force the hatch cover open with their bare hands. According to one of the surviving convicts, the guards opened fire to force them back, and at least one prisoner was struck by a bullet and killed. In a later inquiry, Moxey would dispute the claim, saying that the guards had only been stationed over the hatchways to keep the panicking prisoners contained below deck until the women and children had safely been evacuated. In fact, the inquiry reads like the minutes of a mutual appreciation society meeting, each officer praising the efforts of the others in saving so many lives.

Fifteen minutes after striking the rock, the deck was awash with water, and the last of the boats carrying 40 people had left the stranded vessel. Captain Moxley was among them, having been pulled from the water after he became trapped between floating timbers.

By this time, the guards watching over the hatchways had left in the last boat. The trapped convicts were now able to force their way on deck to find it deserted. But some 50 or so prisoners had been too ill to save themselves. Most had been suffering from scurvy and had drowned where they lay unable to escape the rising water.

After putting the survivors ashore, Moxley returned to the ship and began taking off the convicts. By the time he had reached the George III for the third time, a schooner sent from Hobart had arrived and was taking off the last of the survivors.

One hundred and thirty-four people lost their lives. Three of them were passengers – a woman and two children – and two were members of the ship’s crew. Convicts made up the remaining 128 fatalities. Most never had a chance, trapped in the hold as the water rose around them.

The next morning, a convict named John Roberts was found dead, lashed to a ringbolt in the surgeon’s cabin. It seems he could not swim, so he had tied himself off, hoping to be washed ashore as the ship broke up. Despite the heavy loss of life, 160 people were saved. They were all taken to Hobart, cold, wet, and thoroughly exhausted from the ordeal.

The inquiry into the loss of the ship found no one was to blame. It concluded that the George III had struck a rock not recorded on the chart. Then it came time for the inquiry to consider the treatment of the convicts. No officer admitted to ordering the prisoners to be confined below deck as the hold flooded with water. The Corporal of the guard testified that the muskets were only used to “intimidate” the prisoners, and only one shot was fired, and that into the air. No one was held accountable for the loss of so many prisoners.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.

Leave a comment