In September 1789, HMS Guardian sailed from Portsmouth, England, with much-needed supplies for the newly established penal settlement in New South Wales. But its voyage was cut short when it struck an iceberg in the Southern Ocean and began filling with water.

After an uneventful passage south, the Guardian had stopped at Table Bay (present-day Cape Town) for a fortnight in early December. There, they took on board plants and livestock destined for the colony before setting off across the Southern Ocean for Australia.

The sea conditions were almost ideal, except for a dense fog. There was little swell, and a gentle breeze filled the sails, pushing them east. Late on the afternoon of 24 December, when they were about 2,000 km away from the nearest land, the fog lifted, revealing an iceberg about six kilometres away.

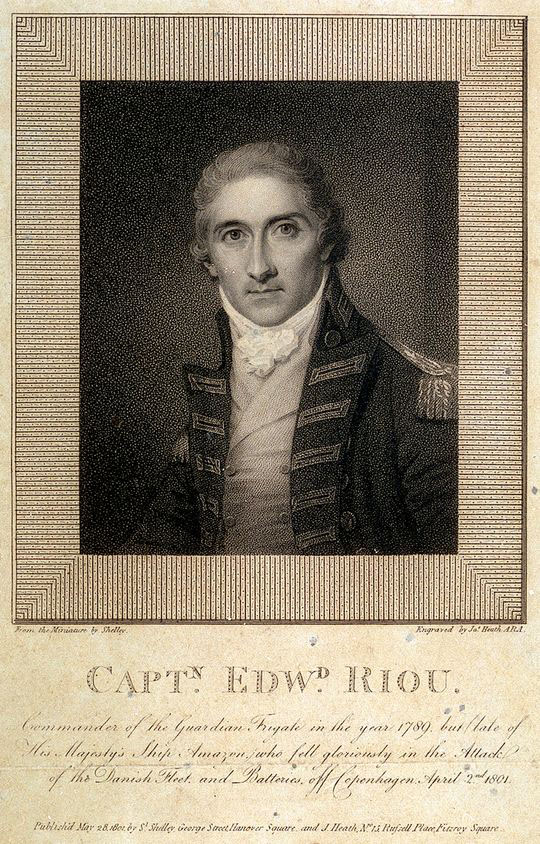

After two weeks at sea, the ship’s water supply had been depleted by the additional animals and plants they were carrying. The captain, Lt. Edward Riou, seized the opportunity to resupply. He brought the Guardian to within 500 metres of the towering white mountain and sent two boats out to gather blocks of ice that were floating in the sea.

By the time the heavily laden boats returned it was about 7 p.m. and the fog had once again enveloped the Guardian. By quarter to eight, Riou could barely see the length of his ship.

Then, without warning, the Guardian crashed stern-first onto a submerged ice shelf projecting out from the berg. The force of the collision violently shook the vessel, causing the rudder to snap off. Riou was able to use the wind and the sails to back his ship off the ice, and for a brief moment, it seemed that disaster had been averted.

However, upon sounding the wells, the carpenter reported that they were taking on a lot of water. The ship had sustained serious damage below the waterline. Riou ordered the pumps manned and the ship lightened. The crew started by throwing the livestock penned on deck over the side. They then began bringing stores up from the hold, and they were also tossed into the sea.

By 10 p.m., it was clear that all the hard work was not going to save the ship. The water continued to gain on the pumps as the ship began to sit lower in the water. Soon she was so low that waves swept over the deck, threatening to pour into the hold through the open hatchways.

Efforts to save the ship continued through the night and the next day. By now, the weather had deteriorated. The wind was raging around them, and mountainous seas rose, crashing into the stricken ship. By now, the crew were exhausted from their continuous exertions at the pumps and jettisoning cargo. Lt Riou finally accepted the inevitable and gave the order to abandon ship.

There were 123 souls on board the ship, but the five lifeboats would only carry half that number. Riou, a maritime man to his core, had already decided he would remain with his ship to the end. But he encouraged anyone who wished to do so to take to the boats where they might stand some chance of surviving.

One lifeboat was lost immediately when it was lowered into the sea, but the other four got away and were soon out of sight. Sixty-two people chose to remain with the ship, including 21 of the 25 convicts being transported.

To Riou’s and everyone else’s great surprise, the Guardian did not sink. Though she sat very low, her deck awash with frigid water, she remained afloat, barely. They would later learn that the cargo of barrels still trapped in the hold provided just enough buoyancy to keep the stricken vessel from sinking. Riou would also later discover that most of the ballast had been lost through a rent in the hull.

A sail was draped under the ship to stem the inflow of water. The pumps were manned around the clock, and they slowly limped back to Table Bay. The relentless cold and wet conditions and sheer physical effort made the passage brutal. However, nine weeks later, they made it to False Bay, where the Guardian would soon break up on the beach.

Of the 60 passengers and crew who had taken to the boats, only 15 survived. They were rescued by a passing ship after being adrift for nine days. The three other lifeboats that got away from the Guardian were never heard of again.

Lt Riou was cleared of blame for the loss of his ship and was later promoted to the rank of Captain. He praised the performance of his officers and men and sought pardons for the convicts who had worked so resolutely to save the ship. But by the time the recommendation reached Port Jackson, one of the convicts had already been hanged for stealing, and six others had gone on to commit additional crimes and their pardons were revoked. But 14 men had their sentences overturned.

(C) Copyright Tales from the Quarterdeck / C.J. Ison, 2022.

To receive notifications of future blog posts enter your email address below.

Leave a comment