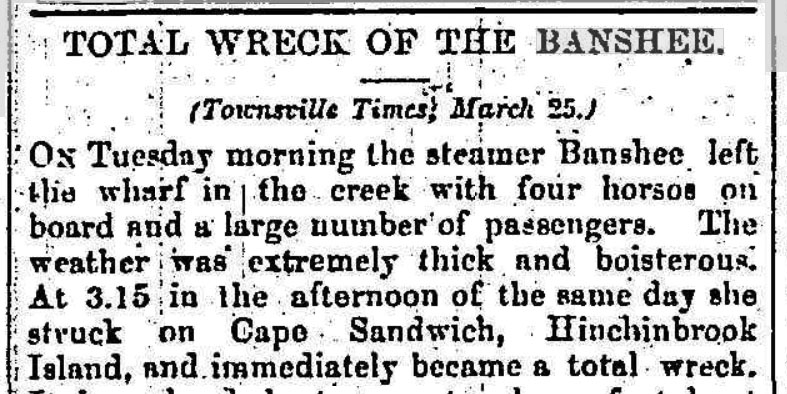

The Banshee steamed out of Townsville at 6 o’clock on the morning of Tuesday, 21 March 1876, bound for Cooktown, some 240 nautical miles (450 km) up the Queensland coast. Captain Daniel Owen had command of the 58-ton steamer and its crew of 10 men. On this trip, the Banshee was carrying 30 paying passengers, and 12 stowaways. Almost everyone was on their way to the Palmer River, where gold had recently been discovered. But disaster would strike long before they reached their destination.

A moderate breeze blew from the southeast, accompanied by some drizzling rain, as they left Townsville. But nothing about the dismal weather hinted at the violent storm that would engulf them seven hours later. At 1.30 p.m., when a few kilometres off the southern end of Hinchinbrook Island, they were lashed by hurricane-force winds, high seas, and torrential rain. Visibility was reduced almost to zero.

Captain Owen did not see land again for over an hour as he steered a north-north-westerly course along Hinchinbrook’s east coast. In his 35 years at sea, he had never experienced such ferocious weather. So, he decided to exercise caution and seek shelter at Sandwich Bay. Once some normality had returned to the world, he would continue on to Cooktown. Captain Owen ordered the engines slowed to half speed and he placed a lookout forward to warn of any dangers.

Then, a little after 3 o’clock, the lookout sighted land dead ahead. The rocky cliffs of Cape Sandwich loomed out of the pelting rain before them. Captain Owen ordered the helmsman to steer “hard a port” and for the engines to increase to full speed. The bow started to come around, but it was too little, too late. The Banshee struck aft and was slammed broadside onto the rocks. Had they cleared that promontory, they would have made it safely into the sheltered waters beyond. But that was not to be.

The ship almost immediately started breaking up. The saloon house gave way under Captain Owen’s feet. “I jumped from the saloon to the top of the steam chest, and from there to the top of the house aft,” Owen later recalled, “and stuck to the mizzen rigging.”

Around the same time one of the passengers, Charles Price, grabbed hold of the boom as the ship ran aground, but when the funnel came crashing down, it knocked him onto the deck. From there, he climbed up on the side rail and leapt onto the rocks. Not all the passengers were so lucky. Many jumped into the sea in panic and drowned before they could scramble to safety. Price went to the aid of one female passenger clinging to the rocks as the waves crashed about her. He reached down but only got a handful of hair before she was swept away.

The ship’s stewardess had a lucky escape. She was seen clinging to a piece of wreckage in that dangerous space between the ship and the rocks. Before anyone could get to her, she was dragged under the vessel before coming back up again. This time, she caught hold of a rope and was pulled to safety. Price tried to save another passenger who he saw struggling to get clear of the waves. But before he could reach the man, he was washed from the rocks and crushed by the ship.

Another pair to have a lucky escape were the Banshee’s cook and a stowaway. They had remained with the ship until it was washed high on the rocks and then stepped off through a rent in the hull.

Captain Owen lost his perch in the mizzen rigging and found himself fighting for his life in the water. Twice he reached the rocks and twice he was washed back out into the cauldron. But on the third attempt, he got a firm hold and was able to clamber to safety above the pull of the waves.

A passenger named Elliot Mullens was reading in the saloon when he heard someone call, “We are going aground.” He rushed onto the main deck just as the Banshee struck. Mullens climbed onto the bridge and, from there, launched himself across to a rock but was immediately washed off by a giant wave. Fortunately, he latched onto another rock, and despite being pummelled by successive waves, he scrambled out of the danger zone somewhat unscathed.

“I turned, and just then the saloon … was smashed to atoms, burying beneath it four women and four children, whom we never saw again,” he later recalled. “Five minutes from the time of striking, all was over – all were saved or hopelessly gone from our sight forever.”

In all, 17 people lost their lives, including all the children and women on board, except the stewardess. The survivors, most nursing deep cuts, bruises or broken bones, spent a cold, wet and miserable night on land. The next morning, two bodies were found washed ashore. Captain Owen held a brief service over them as they were buried where they lay.

By now, the storm had blown itself out, leaving a dead calm in its place. Six men volunteered to cross Hinchinbrook’s thickly forested and mountainous interior so they could signal the small settlement of Cardwell for help. Meanwhile, Captain Owen and everyone else remained where they were, but they did not have long to wait to be rescued.

Around 6 p.m., someone cried out, “Sail Ho.” And, sure enough, there was a sailing vessel out to sea heading south. A large red flannel blanket was hastily hoisted on a makeshift mast, and everyone waited, praying that they would be seen.

Five minutes later, the schooner The Spunkie turned towards land to investigate. But it was only by chance that the survivors had been spotted. The Spunkie’s mate had recently purchased a new telescope and was want to look through it at any opportunity. Luckily, when he brought it to his eye this day, he spotted the red flag and the bedraggled survivors lining the shore. By 10 o’clock that night, everyone had been transferred to the schooner, and they continued on their way to Townsville. The six men who crossed the island were picked up by the steamer Leichhardt as it was passing through the Hinchinbrook Passage.

A Marine Board Inquiry concluded the Banshee was lost due to the stress of the weather. Although they believed that Captain Owen had erred in not heading further offshore than he did, they found that “he acted as he believed for the best under very trying circumstances.”

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.