At midday on 8 September 1859, the 749-ton merchant shipSapphire weighed anchor and began slowly making her way out of Port Curtis (present-day Gladstone, Queensland). She was ultimately bound for India via Torres Strait, with a consignment of 60 Australian horses purchased by the British Indian Army. But before the ship could clear the natural harbour, she ran aground on a sandbar and had to wait for the rising tide to lift her off. So began a voyage that would cost 18 men their lives and last five gruelling months, only for the few survivors to wind up back where they had started. Their story is a remarkable one of perseverance in the face of unimaginable hardship, served with a healthy measure of good luck.

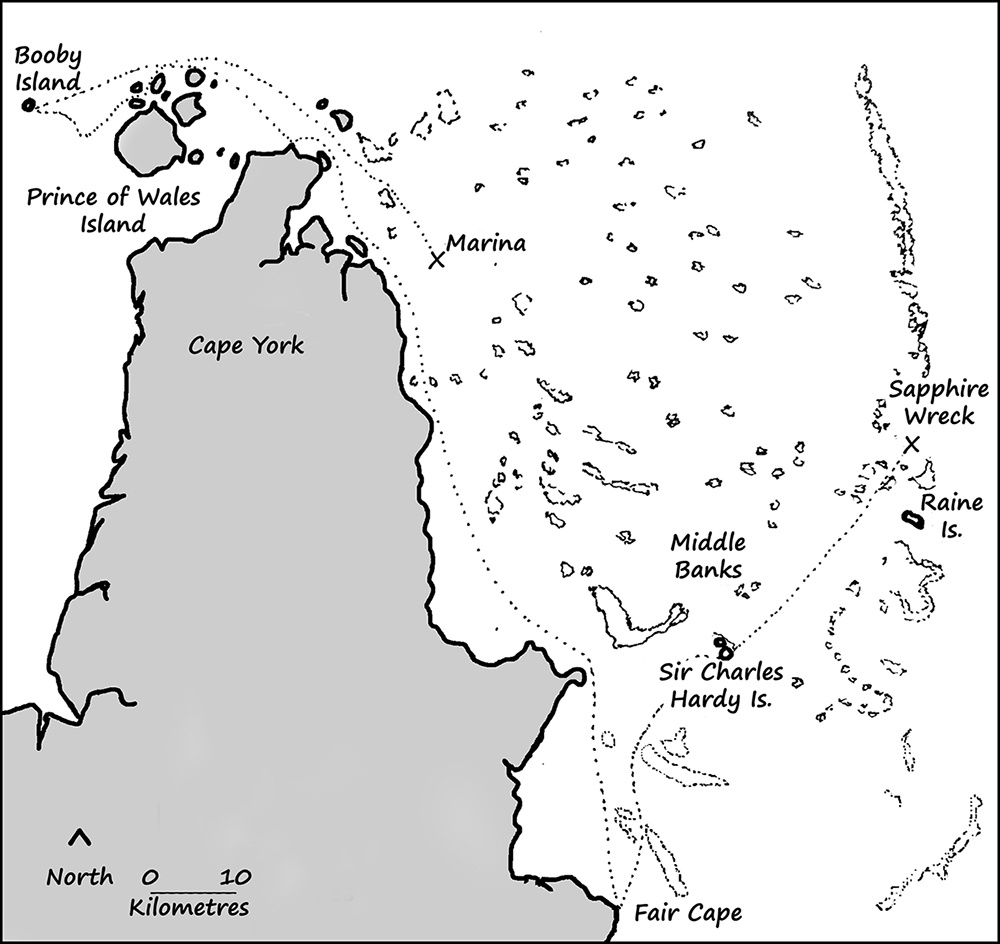

The Sapphire bore out into the Coral Sea and then headed north outside the Great Barrier Reef. On 23 September, Captain Bowden calculated he was somewhere off Raine Island. That afternoon, the lookout sighted a line of breaking surf heralding the outer edge of the reef. Bowden had the ship put about, and they tacked back and forth through the late afternoon. Captain Bowden intended to hold his position in deep water overnight and make his way through the reef first thing in the morning.

But shortly after sunset, the alarm was raised. A lookout sighted a long, uninterrupted curve of white water directly in their path. By the time the ship responded to the call to pull hard about, the breakers were just 500 metres off the leeward bow. There was now insufficient sea room to turn the ship around and point her back out to sea. The Sapphire struck the coral reef broadside. Huge waves swept her deck. The force of the collision brought down the fore-top-gallant mast, and one of their lifeboats was swept from its davits. The ship heeled over, and all seemed lost. Captain Bowden ordered the main mast cut away, hoping the vessel might right itself. When the mast came down, it landed on the deck, smashing the longboat to pieces. It also brought down the mizzen mast, which in turn crashed onto the lifeboat, damaging it. Within minutes, three of the Sapphire’s five boats were lost. Everyone spent a harrowing night sheltering as best they could while the terrified horses remained trapped in the hold.

Breaking with maritime convention, by leaving his ship, Captain Bowden set off in the morning to search for somewhere to land. First Mate William Beveridge was left in charge of the stranded vessel. Beveridge began preparations to abandon the ship and also had the carpenters try to repair the two badly damaged boats, only half expecting that Bowden might return. It seems that Beveridge and Bowden did not see eye to eye, and the first mate may even have blamed his captain for running aground. However, Bowden did return to the Sapphire, having found a suitable refuge on Sir Charles Hardy Island about 85 km away.

The Sapphire’s crew of 28 men took to the two surviving boats and headed to the island, abandoning the ship and the 60 horses still trapped below. Captain Bowden decided they should return to Port Curtis, 1,500 kilometres to the south, and they left messages in a bottle hung from a tree telling of their intentions. They set off south on October 6 but immediately encountered strong headwinds. Bowden soon gave up on heading south, turning his boat around to head north, through Torres Strait, intending to make for Booby Island. In another unusual turn of events, Beveridge did not follow suit. He continued trying to push south for another day or two before he also gave up and turned around.

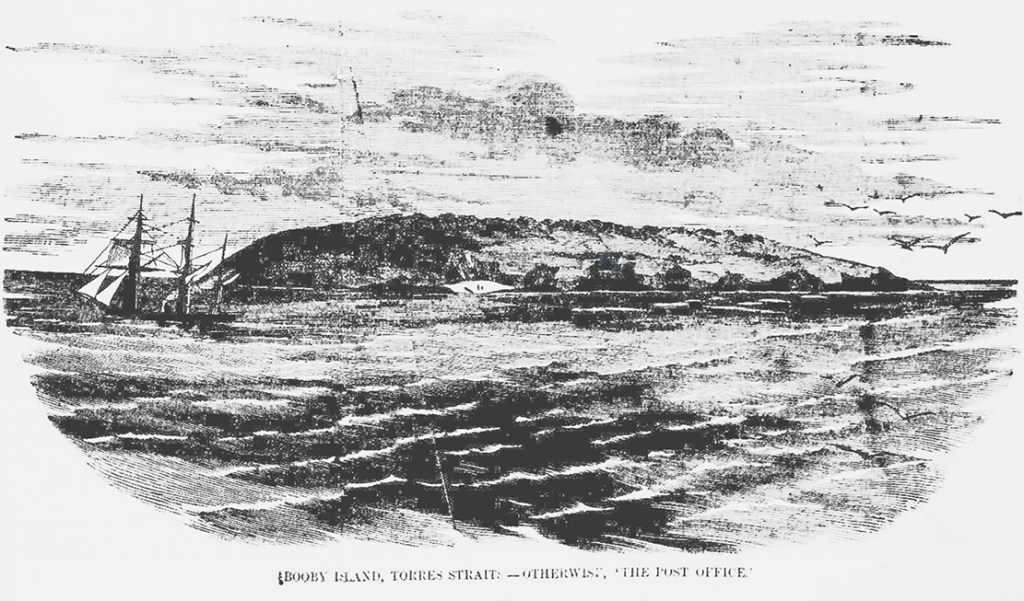

Beveridge reached Booby Island in mid-October to find Bowden and the rest of the men already there. By now, they had been roaming the seas around Torres Strait for almost a month. The provisions they found there were a godsend for the hungry sailors, but they would not last indefinitely. Bowden and Beveridge agreed that they would have to leave there sooner or later. It was approaching cyclone season, and they had not seen another vessel since becoming marooned. They would likely not see another ship pass by Booby Island until April or even May the next year.

Bowden and Beveridge put their differences aside and decided to make another attempt to return to Port Curtis, despite their recent failure. But as soon as they got clear of the island, they were struck by the same contrary winds that had plagued them earlier.

While Beveridge and his boat were off Friday Island, they were set upon by Torres Strait Islanders and one of the men was speared to death. Meanwhile, Captain Bowden’s boat was off Hammond Island. They had stopped to trade with a party of Islanders, but in what seemed like an unprovoked attack, a volley of spears and arrows was launched into their overcrowded boat. Only one man was able to jump clear and swim away. He would later be rescued by Beveridge, who had gone in search of Bowden’s boat.

Beveridge and his men continued pushing back east and eventually made it around the tip of Cape York. They then picked their way through the maze of coral reefs, and their luck finally changed for the better.

They spotted a ship in the distance, the first they had seen since abandoning their own vessel some six weeks earlier. But, as they drew closer, they found it was deserted. The ship proved to be the barque Marina, which had run aground around the same time the Sapphire had been wrecked. It too had been abandoned by its crew, and they had also made it to Sir Charles Hardy, reaching it only hours after the Sapphire castaways had left. Miraculously, the Marina had floated off the reef on a spring tide only to drift around Torres Strait for the next several weeks.

The Marina’s crew had then set off south for Port Curtis, and after 43 days of arduous sailing, they made it safely to port and notified the authorities of the loss of their own ship and also of the Sapphire. HMS Cordelia was dispatched north to search for the Sapphire’s missing men. However, she only steamed as far as Cape Upstart, thinking the lost sailors could not still be any further north. But they were wrong. By now, it was late January 1860, and the Sapphire’s crew was anchored off Lizard Island in the Marina, 500 km further north.

Back in late November, Beveridge had decided they should sail the Marina to Port Curtis rather than try to do so in their small pinnace. Setting off on the 26th, they battled the same contrary winds and currents that had previously frustrated them. For the next two months, they made painfully slow progress. They anchored for days and weeks at a time, waiting for the south-easterlies to fall off. In the first month, they travelled just 180 km.

They spent tiring Christmas Day kedging the stranded barque off a sandbar, and they would run aground twice more in the weeks that followed. The Marina’s hull was so damaged that water flowed freely in and out of the hold. The only thing keeping the ship afloat was her cargo of tightly packed Kauri logs.

On 9 February, they were anchored off Palm Island. In the past two and a half months, they had covered a little more than half the distance to Port Curtis. They still had another 800 km or more to go. All seemed lost. Their food had all but run out, and they were slowly starving to death.

Finally, their luck turned around. The wind started blowing from the north. They put to sea and made steady progress south. Three days later, Beveridge sighted Cape Upstart off the port bow. The next day, they were cruising through the Whitsundays. They were now only 400 km from Port Curtis. A couple of days after that, they crossed Keppel Bay, and the next day, 17 February, they anchored off Facing Island just outside Port Curtis. No one had the strength to manoeuvre the crippled vessel into port. They took to the Sapphire’s pinnace again and surprised everyone with their return, for they had long been given up for dead.

The Sapphire’s full story is told in A Treacherous Coast: Ten Tales of Shipwreck and Survival from Queensland Waters, available as an eBook or paperback through Amazon.

© Copyright C.J. Ison, Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2021.

Enter your email address in the form below to be notified of new posts.