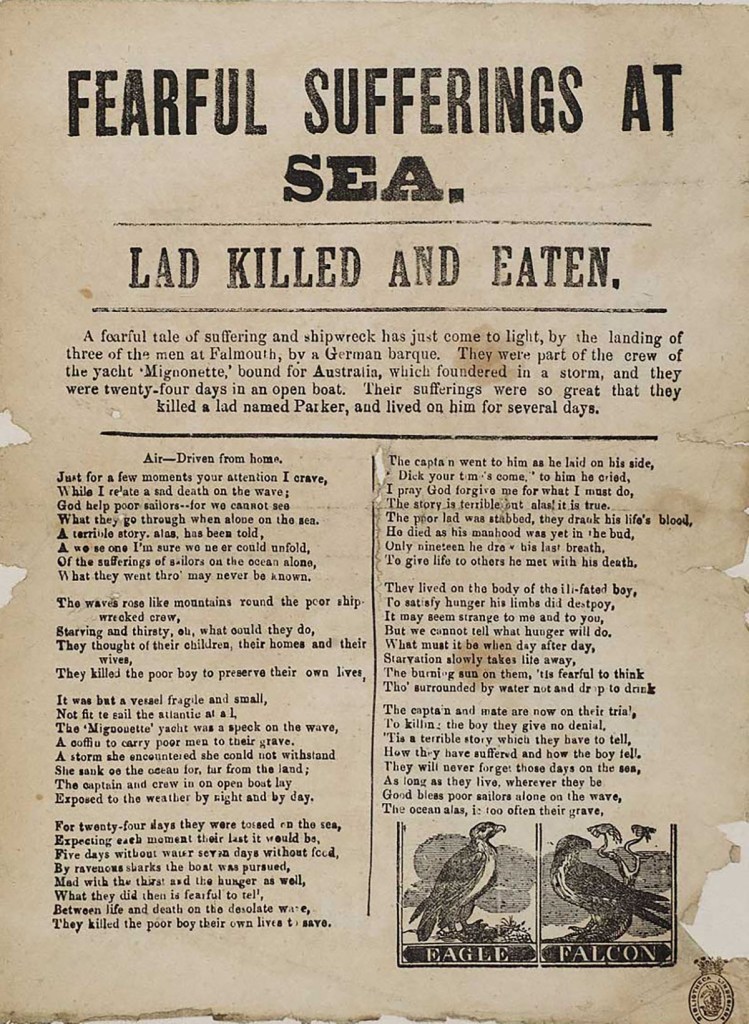

Genuine verifiable instances of cannibalism among shipwreck survivors are remarkably rare. But when they have occurred, those involved have often been met with revulsion and sympathy in equal measure. Such was the case with the survivors of the small yacht Mignonette, which foundered in the Atlantic Ocean on its way to Australia in 1884.

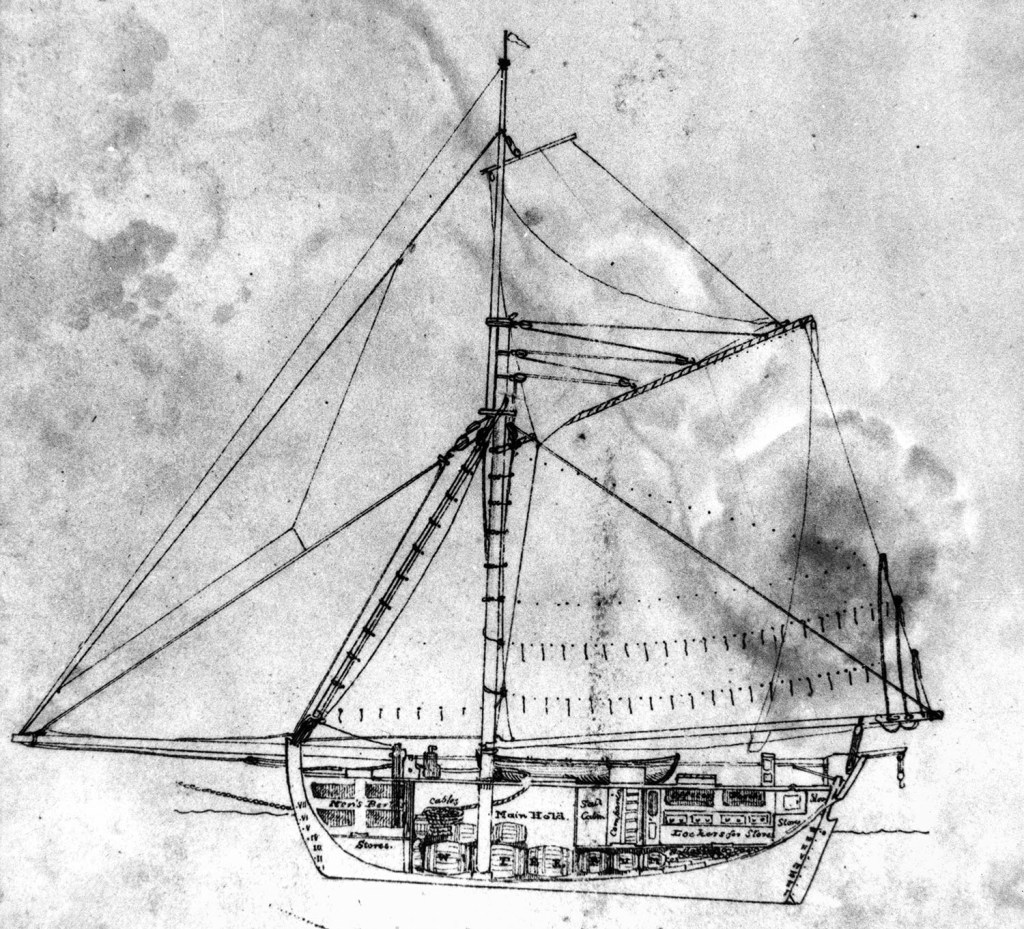

The Mignonette was a small yacht of about 33 tons. It had been purchased in England by Sydney barrister and Commodore of the Sydney Yacht Club, John Want. He hired a respected master mariner named Thomas Dudley and a crew of three to sail the vessel to Australia while he returned home by a regular steamer service in more salubrious surroundings.

The Mignonette sailed from Southampton on 19 May 1884 and briefly stopped at Madeira off the Moroccan coast around the middle of June. Then, nothing further was heard of her until 6 September, when Dudley and two of his crew returned to England after being rescued at sea by the German barque Montezuma. The world then learned the horrifying truth of their ordeal. Six weeks after leaving England, they were far from land, some 3000 kilometres south of the equator and 2500 kilometres off the Namibian coast. By now, the weather had turned foul. The seas ran high, and Captain Dudley was running before a strong wind, taking them further south. On the afternoon of 5 July, the Mignonette was struck by a gigantic rogue wave that had risen from nowhere and crashed into her side. The yacht’s hull was stoved in.

The mate, Edwin Stevens, was at the wheel and barely had time to call out a warning before the monster wave struck. Fortunately, Dudley grabbed hold of the boom and held on as a wall of water swept across the deck.

The Mignonette immediately started filling with water. Dudley ordered the men to prepare to abandon ship. They got the lifeboat over the side while he went below to gather provisions. By then, seawater was already swirling around the cabin interior. He only had time to grab a couple of tins of what he thought was preserved meat, before he raced back on deck and leapt into the dinghy as the Mignonette sank below the waves.

Dudley, Stevens, Edward Brooks, and seventeen-year-old Richard Parker spent a frightening night in the tiny four-metre dinghy as the storm raged around them. When Dudley opened the tinned provisions, he discovered they contained not meat but preserved turnips. Even worse, they had no fresh water.

For the next five days, they subsisted on morsels of turnip and tiny quantities of rainwater, but it was never enough. Then their luck improved, at least for a short while. They captured and killed a turtle that had been basking on the sea’s surface.

By day 19, the last of the turnips and the turtle meat had long gone, and the young cabin boy, Parker, had started drinking seawater to quench his burning thirst. He was now lying in the bottom of the boat in a delirious state.

Wracked with hunger and despair, that night, Thomas Dudley suggested drawing lots to see who should be killed to provide sustenance so the rest might live. Brooks wanted no part of it and told the others he believed they should all live or die together.

Dudley and Stevens discussed their options and felt that, as they were both married men with families to support, it should be Parker they butchered, as he was already close to death. The matter was settled.

Dudley prayed for forgiveness for what they were about to do, then, as Stephens held Parker down, Dudley pulled out his knife and slit the boy’s throat. Brooks turned away, covering his eyes with his hands, but he could not block out Parker’s feeble pleas for mercy. As Parker’s blood drained from his body, they caught it in an empty turnip tin and drank it. Brooks, despite his horror, was unable to resist taking a share. The three men fed on Parker until they were rescued by the passing barque Montezuma, five days later.

When Captain Dudley returned to England, he reported the loss of his vessel and the hardships they had endured afterwards, including the death of the delirious Parker. As abhorrent as his actions were, he believed he had committed no crime. In his mind, he had sacrificed one life to save three. But the police saw it otherwise. He and Stephens were remanded in custody to stand trial for the capital crime of murder.

There was widespread interest in the tragic story in both Britain and Australia. Many people were sympathetic towards the captain and his first mate. But there were also those who felt the pair had acted prematurely in killing the dying Parker.

At their trial, Dudley and Stephens pleaded not guilty, their barrister arguing they had acted in self-defence. He used the analogy that if two shipwrecked men were on a plank that would only support one, one or the other could be excused for pushing away the other man to drown. For, he argued, were both men to remain on the plank, both would perish.

The judge didn’t see things that way. In summing up the case, he told the jury:

“It was impossible to say that the act of Dudley and Stephens was an act of self-defence. Parker at the bottom of the boat was not endangering their lives by any act of his. The boat could hold them all, and the motive for killing him was not for the purpose of lightening the boat, but for the purpose of eating him, which they could do when dead, but not while living. What really imperilled their lives was not the presence of Parker, but the absence of food and drink.”

The jury found the pair guilty, and the judge sentenced them to death, but it appears there was little likelihood that the death sentence would ever be carried out. Even Parker’s family had forgiven the two men on trial. After waiting on death row for six months, both sentences were commuted to time served, and they were released from custody.

It was generally agreed that they had acted as they did under the extreme duress of being lost at sea for so long without food or water. No one felt that justice would be served by punishing the two men any more than they had already suffered.

Copyright © C.J. Ison, Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2021.

To be notified of future blog posts please enter your email address below.