On Friday, 29 December 1893, around 11 o’clock in the morning, two ladies were strolling along Sorrento Ocean Beach on the Mornington Peninsula when they discovered an unconscious man washed up on the sand. He would prove to be the sole survivor of the steamer Alert, which sank during foul weather.

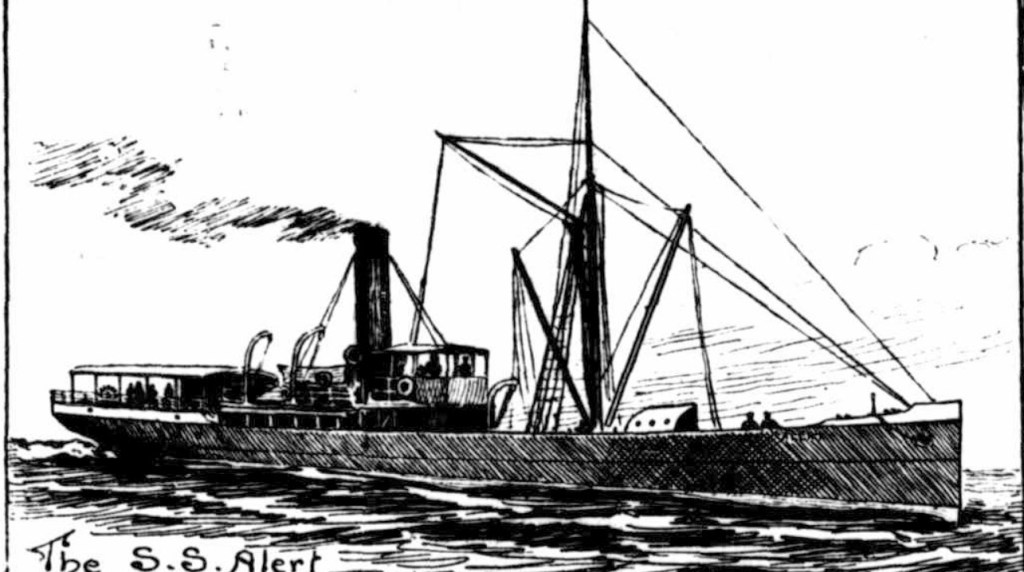

The SS Alert had left Bairnsdale on Victoria’s southeast coast at 4 p.m. two days earlier, bound for Port Albert and Melbourne. But a little more than 24 hours later, she would be lying at the bottom of Bass Strait off Jubilee Point.

The Alert was a 16-year-old 243-ton iron screw steamer owned by Huddart and Parker. She had recently been refurbished and, for the past two months, had been carrying passengers and cargo between Gippsland and Melbourne. Prior to that, the Alert had been a favourite of the excursion fleet, which ferried passengers between Melbourne and Geelong.

From the moment the little steamer cleared the Gippsland Lakes, she felt the full fury of a storm lashing the Victorian coast. Nonetheless, Captain Albert Mathieson thought the sea conditions were nothing his ship could not handle. They stopped briefly at Port Albert, 150 kilometres down the coast, to deliver some cargo and then continued on towards the entrance to Port Phillip Bay and respite from the atrocious weather.

By 4 p.m. Thursday, they were off Cape Schanck, just 30 kilometres short of Port Phillip Bay. Owing to the trying conditions, Captain Mathieson had remained on the bridge the entire trip. Such were the conditions that it required two men at the helm to keep the steamer pointed on its course. Then disaster struck.

About half an hour later, the Alert was struck by a massive rogue wave that swamped the deck with tons of water and pushed the steamer over onto her side. Then, they were hit by a second large wave before the water from the first had time to drain away. The saloon skylight and a porthole window were smashed, and the sea poured in. The helm was unresponsive by now, and the ship’s lee rail was pushed underwater. Another wave swept over the bridge as seawater snuffed out the struggling steamer’s engine fires.

The captain ordered everyone to don their lifebelts as he vainly tried to head the stricken steamer into the wind, but to no avail. He ordered the lifeboats to be lowered, but one had already been swept off its davits, and the other had seas continuously sweeping over it. There was nothing anyone could do now.

Robert Ponting, the ship’s cook, joined the rest of the crew on deck, and minutes later, the Alert went to the bottom. Ponting climbed onto a hatch cover, but in the turbulent seas, it kept turning over and flipping him into the water. He eventually lost hold of it altogether and began swimming. He spotted the ship’s steward nearby and kept pace with him. Ponting and the steward remained together until the poor fellow could no longer keep his head above water and drowned. Around this time, Ponting spotted Captain Mathieson swimming strongly, but lost sight of him again shortly after.

Ponting spent the night swimming about in the cold Bass Strait waters within view of the Cape Schanck Lighthouse. The cold water chilled him to the bone, and he eventually passed out. He continued drifting with the current, slowly pushing him towards land. Then, around daybreak, he felt himself being tumbled ashore and used the last of his strength to drag himself away from the pull of the surf. He had spent over 12 hours in the water and would spend another five or six hours passed out on the beach.

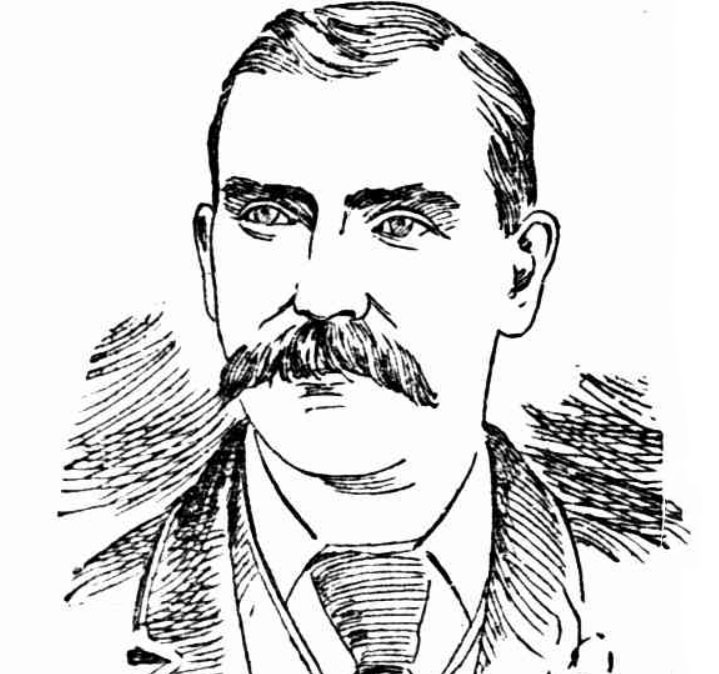

When, around 11 o’clock, he came too, he found he was surrounded by a group of ladies and a gentleman who had been walking along the beach. The first ladies to discover the unconscious man had called on the others to come to Ponting’s aid. Among his saviours was Douglas Ramsay, a doctor on holiday from his practice in Elsternwick. At first, Ramsay thought that Ponting was dead. He had tried to find a pulse but could not. and “his eyes were shut and all sanded over, his nostrils were also clogged with sand, and his body was stiff and cold,” he later recalled. The doctor didn’t give up, though. He opened Ponting’s mouth and poured some drops of brandy down his throat while vigorously working his arms “to restore animation.” After about ten minutes of this bizarre medical attention, Ponting began to show signs of life.

Ramsay then dragged him behind a rock to shelter him from the cold wind and one of the ladies removed her jacket and wrapped it around his frozen feet. A couple of the other ladies began the long walk back to their carriage and headed to Sorrento for assistance. Meanwhile, Dr Ramsay continued with his ministrations. While they were waiting for help to arrive, another man happened on the scene while walking his giant St Bernard dog. He had his huge canine nestle up against Ponting for warmth. That, and a steady administration of medicinal brandy, brought some colour back to Ponting’s cheeks.

After a while, he was able to tell his rescuers his name and what had befallen him. He also asked that someone send his wife a telegram to tell her he was alive. He did not want her to think he had perished with everyone else when news of the shipwreck broke. Eventually, he was taken to the Mornington Hotel in Sorrento, where a couple of local doctors cared for him. As apparently was best practice in such cases during the late 1800s, the good doctors rubbed his entire body with mustard and poured hot brandy down his throat. In response – or perhaps despite it – Ponting made a full recovery.

Over the next couple of days, several bodies and much wreckage washed up on Mornington Peninsula’s rugged ocean beaches. In all, 14 men lost their lives: 11 crew and three passengers. Robert Ponting was the only one to survive the catastrophe.

A marine board inquiry concluded that the Alert had insufficient ballast for the prevailing sea conditions, which had made her ride higher in the water and less stable on her final voyage. The board also felt that Captain Mathieson should have found shelter in Western Port rather than continue down the coast to Port Phillip Bay. It chose not to give an opinion on the captain’s handling of the vessel in its final minutes due to insufficient evidence.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.