As anyone who has ventured across to K’Gari (Fraser Island) knows, the rusting wreck of the old luxury passenger liner SS Maheno makes an imposing presence on the long sandy beach, which serves as the island’s main highway. She had been swept ashore during a cyclone 90 years ago while on her way to be broken up in a Japanese scrapyard. It was an inglorious end for a steamer that was once one of the fastest luxury liners on the trans-Tasman run.

The SS Maheno was built at William Denny and Brothers shipyards on the Clyde River in 1905 for the New Zealand-owned Union Steam Ship Company. She measured 122m in length and had a gross tonnage of 5,300 tons. The vessel was equipped with powerful steam turbine engines, which were revolutionary for the time. They could push her along at an impressive top speed of nearly 20 knots (36km/h).

For much of her career, she carried cargo and passengers between Sydney, Melbourne, and Hobart in Australia, and Wellington, Auckland, and Dunedin in New Zealand. On one occasion, the Maheno made the dash from Sydney to Wellington in just under three days, a record that would remain unbeaten for 25 years. She also occasionally was called upon to carry passengers across the Pacific to San Francisco.

The Maheno was not only fast, but she was also luxurious. She could accommodate 120 passengers in her sumptuous first-class cabins, 120 in second-class and 60 more passengers in third-class. The saloons, dining rooms and other public areas were beautifully appointed, harking back to a bygone era. She was a magnificent example of early 20th-century shipbuilding at its finest.

During the First World War, she served as a hospital ship for Australian and New Zealand forces. She ferried casualties from Anzac Cove to Malta for medical treatment during the Gallipoli Campaign. After the failure of Gallipoli she transported wounded New Zealanders back home before returning to Europe where the war raged on. Between 1915 and 1918, she made several trips back to New Zealand, returning wounded Kiwi soldiers home to their loved ones. She also carried thousands more sick and wounded men from the Western Front across the English Channel so they could receive attention in England.

After the war, she returned to her regular duties crossing the waters between New Zealand and Australia. As she aged, newer ships took over her routes. However, she remained on the Melbourne – New Zealand run until the beginning of 1935 when she was finally retired. Throughout her 30 years of service, she was never involved in a serious accident, a testament to the ship and the captains who commanded her. But on her final voyage, that was about to change.

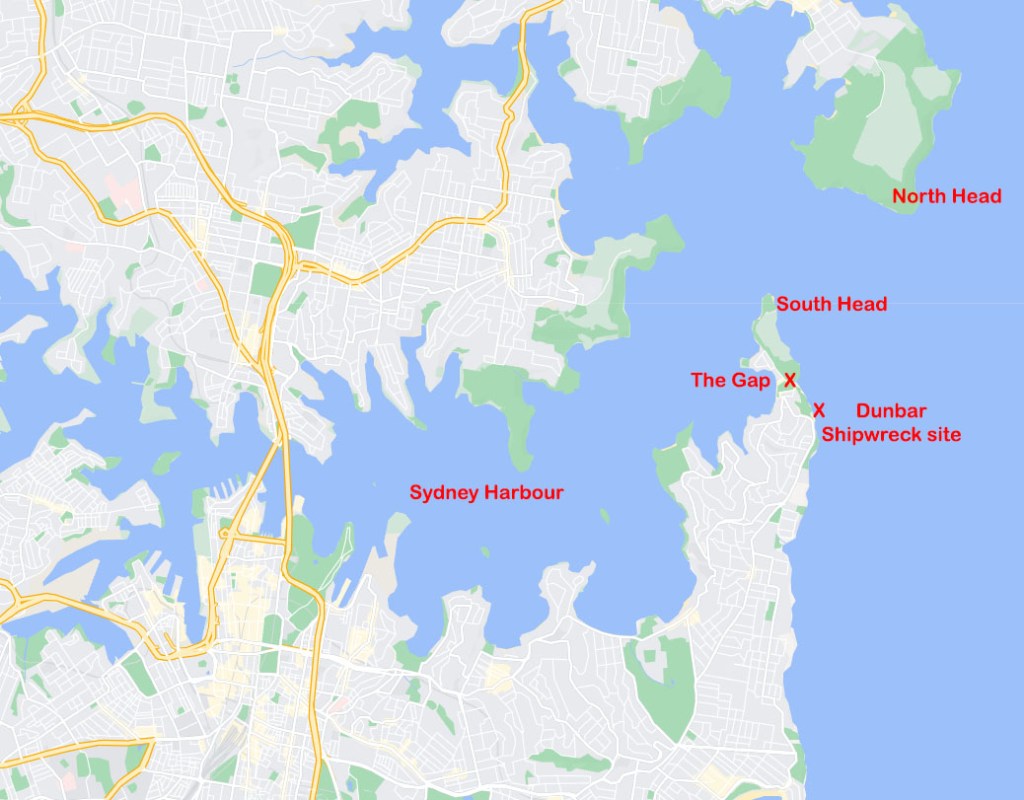

In July 1935, the Maheno left Sydney under tow by the steamer Oonah, another aging vessel destined for demolition in Japan. “Like a minnow towing a whale, the little Oonah set out to tow the Maheno, which towered above her like a giant,” is how the Daily Telegraph described the scene as the two tethered ships made their way down Sydney Harbour to begin their long voyage north.

The first few days were relatively uneventful as the Oonah towed the Maheno up the New South Wales coast. But by the time they reached Queensland waters, the weather had turned nasty. The two ships were caught in a raging storm. Huge swells swept around them, howling gale-force winds ripped at the rigging, and the decks and superstructures were lashed by heavy rain. Despite the thick weather, the ships might have survived, but that was not to be.

The Oonah reported via wireless that she was having problems with her steering. However, the message was garbled, and the call for help went unanswered. Then the captain of the Oonah sent another message reporting that the tow cable had parted and the Maheno was adrift. He also radioed that the two vessels were about 80 km off K’Gari when the Maheno was lost from sight.

Efforts to save the two stricken ships swung into gear. The insurance underwriters dispatched a large salvage tug from Brisbane to assist the vessel, and the Oonah would be rescued without further incident. The Maheno, on the other hand, was now at the mercy of the storm without any means of propulsion. There were grave fears for the eight Japanese sailors on board. But they rode out the maelstrom, and eventually, the Maheno gently made landfall.

A search aircraft sent out from Maryborough spotted the former luxury liner driven broadside onto Fraser Island’s (K’Gari’s) long sandy beach about 30 km south of Indian Head. Her location was then relayed to the Oonah and the salvage tug heading up from Brisbane.

The Japanese crew got ashore safely and were soon greeted by carloads of tourists, who had driven down from the nearby holiday village of Happy Valley to take a closer look at the beached ship.

At first, there were some thoughts of refloating the Maheno, but they were swiftly abandoned, for she was firmly stuck in the sand. She remains there to this day, perhaps the most prominent and accessible shipwreck on the Australian coast.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.