On 27 November 1874, a lookout on the British ship Spectre spotted something floating in the water deep in the Indian Ocean. As they drew near, they realised it was a small boat holding six men. When they came alongside, they found one man was already dead. The other five were barely clinging to life and two of those would soon die. They were the only survivors from the emigrant ship Cospatrick, which had caught fire and sank with the loss of nearly 470 people.

The 1200-ton Cospatrick had sailed from London bound for Auckland with 433 passengers, most of whom were assisted migrants looking forward to starting life afresh in New Zealand. But, just after midnight on 17/18 November, when they were about 750 km southwest of the Cape of Good Hope, smoke was seen coming from the forehatch.

The alarm was immediately raised, and Captain Elmslie rushed on deck. The whole crew were turned out to tackle the blaze thought to have started in the Boatswain’s Locker, where many flammables were stored. Pumps poured water down the forescuttle, hoping to extinguish the fire before it spread. Meanwhile, the captain was trying to turn the ship before the wind in a vain attempt to keep the fire contained to the fore part of the vessel.

As the crew battled the fire, almost all the passengers rushed on deck, fearing for their lives, and screaming for help. Then the Cospatrick swung head to the wind, “which drove the flames and a thick body of smoke aft, setting fire to the forward boats,”* 2nd mate Henry McDonald recalled. He and the sailors fighting the fire with pumps and buckets were forced to retreat aft with the flames licking at their heels. With half the ships’ lifeboats lost Macdonald asked Captain Elmslie if he should lower the remaining two. Elmslie told him “no” but instead to continue fighting the fire.

But, by then, terrified passengers had taken matters into their own hands. As many as 80 people, many of them women, climbed into the starboard boat meant only to carry 30 while it was still suspended in its davits. They buckled under the weight, and when the boat dipped into the sea, it capsized, spilling everyone out. Under the circumstances, no crew could go to their assistance, and they all drowned.

A guard was placed on the port lifeboat, but it was also swarmed by panicked passengers. Flames burnt through the ship’s rigging, and the foremast collapsed and fell over the side. By now, the captain realised his ship was lost. Standing by the helm with his wife and son beside him, he told the few men assembled around him to do what they could to save their own lives.

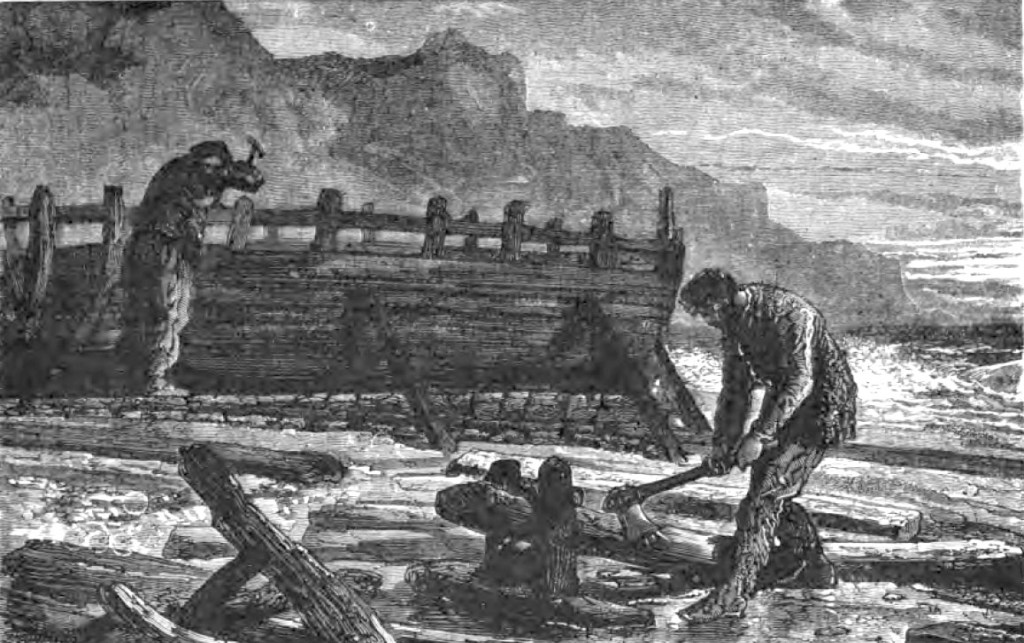

Macdonald and a couple of the seamen tried launching the pinnace which was stored upside down on the deck. But before they could get it over the side, its bow caught fire, and they abandoned it. Macdonald then ordered the port-side lifeboat to be lowered, and as it descended, he jumped on board. Moments later, he was joined by the Chief Mate, who leapt from the Cospatrick as it was fully ablaze. Captain Elmslie was last seen jumping into the sea with his wife. The ship’s doctor followed, carrying Elmslie’s young son.

The boat, carrying 34 people, remained by the Cospatrick throughout the night as it continued to blaze. The main and mizzen masts fell, and then an explosion deep in the hold blew out the stern under the poop deck. This was probably caused by the large quantities of alcoholic spirits, and other volatile liquids stored in the hold.

The next morning, Macdonald found that some of his shipmates had managed to right the starboard boat, and it, too, was full of survivors. They found a few other people clinging to wreckage and hauled them onto the two boats. They remained with the Cospatrick until it finally burned to the waterline and sank on the evening of 19 November. Then, Macdonald took command of the starboard boat while the Chief Mate remained in the portside boat.

They divided the surviving people between the two boats and shared out the available oars. The Chief Mat’s boat carried around 35 people while Macdonald’s carried 30. Neither boat had a mast or sail, but Macdonald got a petticoat from a female passenger, which he used as a makeshift sail fastened to an upright plank. Neither boat had any freshwater or any other provisions. Nor does it seem they had so much as a compass to steer by.

They set a course for where they thought the southern tip of Africa lay some 750 kilometres away. The boats remained together for the next two days, but on Sunday night, 22 November, a gale blew up, and they became separated. The Chief Mate’s boat was never heard of again.

Henry Macdonald kept a daily log of their voyage as any good office would. “Sunday 22, … thirst began to tell severely on us all. … three men died, having first become made in consequence of drinking salt water.”* Four more men died the following day, but before their bodies were dispatched over the side, Macdonald wrote that “we were that hungry and thirsty that we drank the blood and ate the liver of two of them.”* Over the next several days, they would continue to live off the dead.

The weather raged around them, and deaths were a daily occurrence. Early in the morning of Thursday, 26 November, a barque sailed past but failed to spot them among the white caps. They continued drinking the blood of the dead, but they were getting weaker by the day.

On Friday, 27, two more men died, but they had only the strength to throw one of them overboard. “We are all fearfully bad, and had drunk sea water,” Macdonald entered in his log.*

There were now just five men still alive, but only barely. They were all dozing when Macdonald was woken by a passenger, who had gone made with delirium, biting his feet. When Macdonald looked up, he saw that an end to their suffering was at hand. The Spectre, returning home to Scotland from Calcutta, was bearing down on them. The five men were taken aboard, but two of them died soon after being rescued. The three survivors, including Henry Macdonald, were put ashore at St Helena when the barque stopped there for supplies.

An inquiry held in London into the loss was not convinced the fire had started in the boatswain’s locker. It concluded that the blaze was likely caused by a careless match or candle carried by someone breaking into the hold in search of liquor the ship was known to be carrying in large quantities. It recommended that a more robust bulkhead be installed in ships but did not consider whether highly flammable cargo should be carried on the same vessel as so many passengers.

Nor did the inquiry make any firm recommendations regarding the number of lifeboats carried by passenger ships. Even had the crew been able to launch all the Cospatrick’s boats, fewer than half the people on board could have been saved. It simply advised that ship owners should consider some increase in lifeboat carrying capacity. It would take another 40 years and the loss of the Titanic before laws mandated that all ships have enough lifeboats to evacuate everyone in an emergency.

(*) Henry Macdonald’s log was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 26 Feb 1875, p. 3.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.