In 1851, two men accomplished a sailing feat that few thought was possible. They had been the only hands on board the barque Countess of Minto when she was driven from her anchorage during a violent storm. The captain and the rest of the crew were left stranded on a remote desert island. Everyone thought the ship had foundered in the storm, but four weeks later, she sailed into Sydney Harbour. To everyone’s astonishment, the two men had survived and sailed their ship over 1000 kilometres to safety.

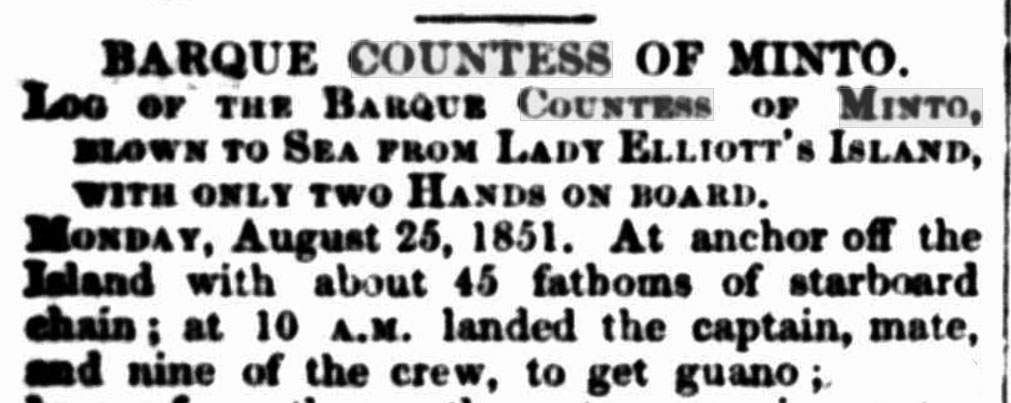

On 25 August 1851, the 300-ton Countess of Minto was anchored off Lady Elliot Island on the Great Barrier Reef to collect guano, a valuable commodity at the time. John Johnson and Joseph Pass had just returned to the ship after taking the captain and the rest of the men ashore to dig for guano. Soon after the pair returned to the ship, the weather began to deteriorate.

By midday, the wind was howling through the rigging, the seas boiled around the ship, and the deck was being lashed by torrential rain. It was now far too dangerous to take the jolly boat ashore to join their shipmates on the island. Johnson and Pass had no choice but to ride out the storm where they were.

The two seamen let out the anchors as far as they would go, hoping they would remain firmly dug into the seabed. The ship surged and the chains strained with each powerful swell, and for a time they held.

Then, around 11.30 that night, a very thick squall struck. The force of the wind and the seas was too great, and the anchors started dragging along the sea floor. The barque was swept out into the deep water of the Coral Sea, somehow missing the island and the nearby reefs. Johnson and Pass had no control over the ship as it bucked and tossed in the tumultuous seas. They could only pray that the vessel would not founder and they might survive the night.

Johnson was the ship’s carpenter, and Pass was the steward. Neither was part of the regular sailing crew, but it is evident that one or perhaps both men possessed a wealth of sailing experience. And, at least one of them knew how to navigate using a sextant and a chronometer.

The pair survived the wild night, and by the next morning, the wind had eased and the men could take stock of their situation. Lady Elliot Island was nowhere to be seen. In fact, no land at all interrupted the horizon in all 360 degrees. They checked for damage to the sailing gear and hull and were relieved to find the Countess of Minto had survived the storm with only superficial injury. The hull, masts, and sails were intact, but they were now drifting aimlessly under bare poles at the mercy of the wind and current.

Both anchors were still dangling at the ends of 45 fathoms (90 metres) of chain. The deck was littered with ropes and other gear that had broken loose but had not been washed overboard. The longboat had been swept off the forward hatch and was now full of water and being dragged along behind the ship. The jolly boat, likewise, was trailing behind.

They released the anchors after being unable to haul them up on their own. They set up a boom with a block and tackle and retrieved the two boats. Then they tidied up the deck. At midnight, they pumped eight inches of water out of the bilge and continued working through til dawn.

They finally hoisted some canvas from the main mast and bore towards the south-east. For the first time since being swept from their anchorage nearly 36 hours ago, they had control of the ship.

On Wednesday evening, 27 August, the winds picked up again after a day of blowing a gentle breeze. They now tried to set a north-westerly course so they could return to Lady Elliot Island and rescue their shipmates. But in the face of contrary winds and hampered by a lack of manpower, they struggled to get back.

For the next eight days, the pair battled the wind and the seas, trying to make it back to Lady Elliot Island. However, despite their efforts, the ship continued to be pushed southward and away from the coast. The winds were blowing from the north, and each time they tried to beat to windward, they would be pushed further south. By Friday, 5 September, Johnson and Pass were utterly exhausted and were now further away from their shipmates than ever.

They finally decided to go with the wind and make for Sydney so they could get help. Now with the wind behind them ,they made good time. The Countess of Minto was off Port Macquarie four days later and only had another 300 km to go before reaching Sydney. There, they fell in with another ship, and its captain came over to see what assistance they needed. Stunned to discover there were only two men on board, he offered to crew the ship and take it the rest of the way to Sydney as long as they officially handed control to him. Johnson and Pass refused, knowing full well that the captain would then be entitled to claim salvage rights. Despite their exhaustion, they figured that they could make it the rest of the way by themselves. The captain left and later returned with a few of his men, offering their help with no strings attached. This time, Johnson and Pass accepted.

On 20 September, the Countess of Minto sailed into Sydney Harbour to be greeted by their captain, who had just arrived and reported his ship lost. Johnson and Pass were commended for their “meritorious conduct,” and the insurance underwriters rewarded each of them with £10.

As fate would have it, the Countess of Minto would be lost a couple of months later after striking ground off Macquarie Island as the captain sought to finish filling his hold with guano.

The Countess of Minto’s incredible story is told in A Treacherous Coast: Ten Tales of Shipwreck and Survival from Queensland Waters, available as an eBook or paperback through Amazon.

© Copyright C.J. Ison, Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

Enter your email address in the form below to be notified of new posts.