In September 1875, the South Australian Government honoured three men for the courage they displayed when the Gothenburg sank with fearsome loss of life. James Fitzgerald, John Cleland and Robert Brazil had risked their lives to save other survivors from the ill-fated steamer.

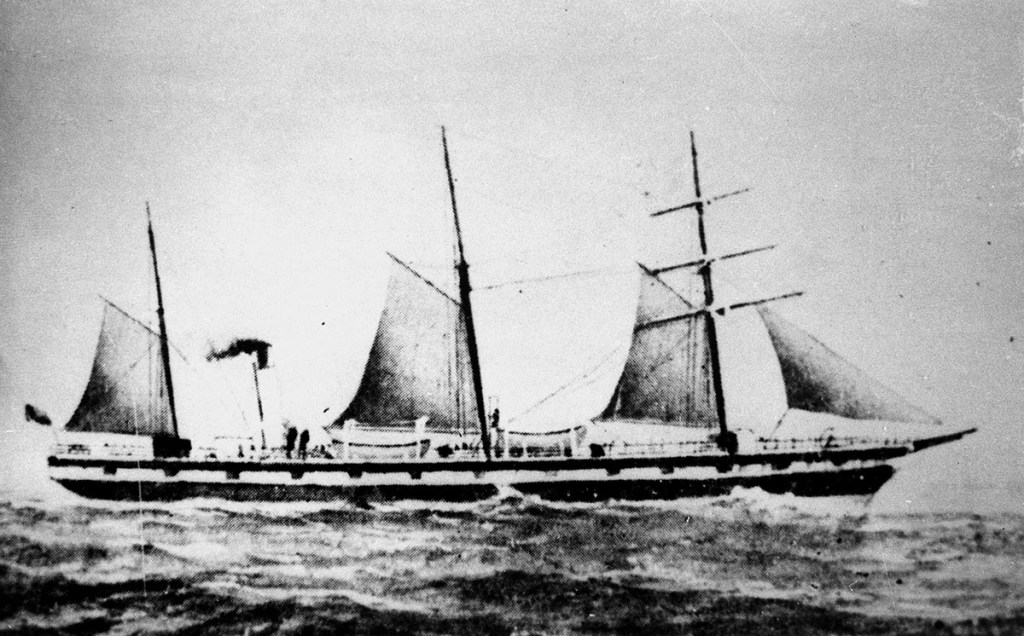

The Gothenburg was a 501-ton steamer, and on this, her final voyage, she carried 37 crew and 88 passengers, 25 of whom were women or children. She departed Darwin on Tuesday, 16 February 1875, bound for Adelaide via Australia’s east coast. By the evening of the 24th, Cape Bowling Green just south of Townsville, would have been visible off the starboard side had it not been obscured by thick weather.

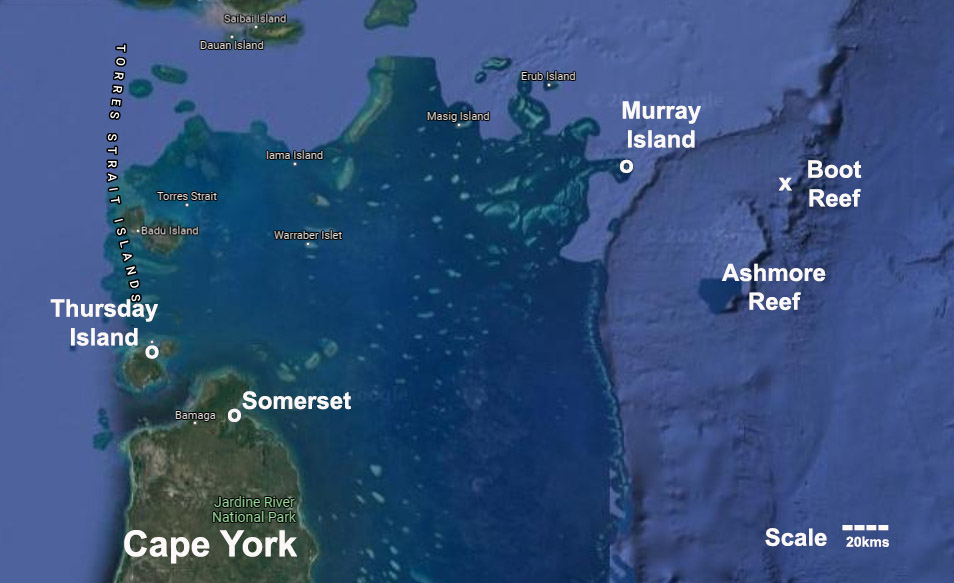

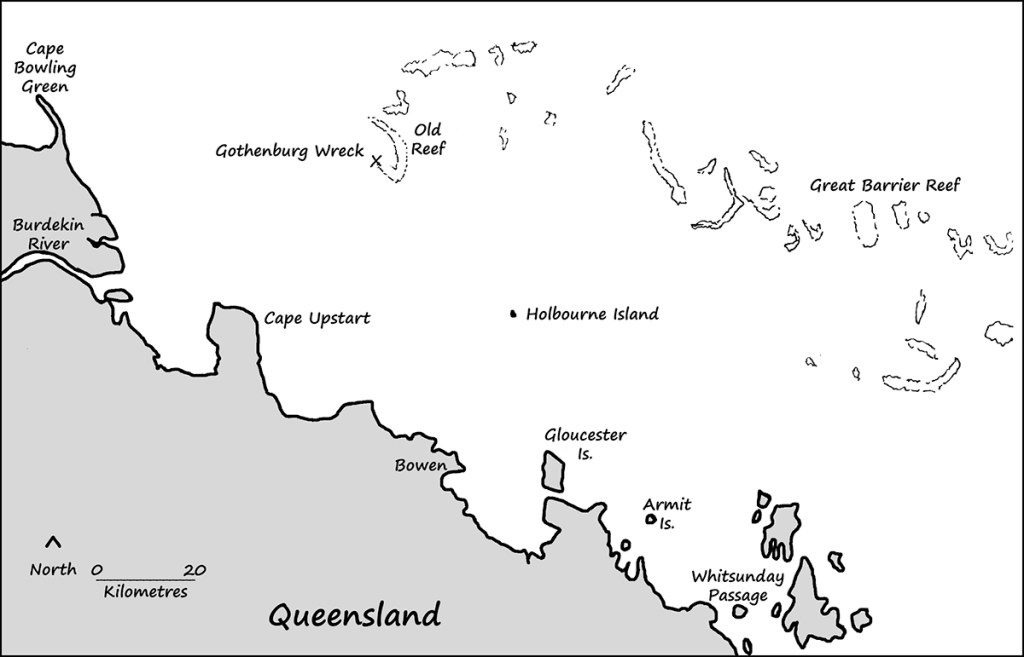

The steamer had been followed by bad weather for most of the voyage down the Queensland coast. With usual landmarks hidden from view, the captain, James Pearce, was relying on his patent log to plot their progress. He thought he now had open seas ahead of him until they reached Flinders Passage, where he would pass through the Great Barrier Reef. It was early evening, and the Gothenburg was cutting through the water at 10 knots (19 km/h). Large swells made the ship roll uncomfortably, upsetting many of the passengers. But then the seas flattened. It should have alerted the captain that they were in the lee of a large reef. But before any action could be taken, the Gothenburg ran onto a vast coral shoal hidden just under the sea’s surface.

The impact was not particularly violent. The iron-hulled steamer had glided along the top of the reef, coming to a halt in less than her own length. By the time she stopped, her stern was still hanging out over deep water. It would transpire that the Gothenburg had drifted further east than Pearce had reckoned on, and they had struck Old Reef just north of Flinders Passage.

Pearce was not particularly concerned at first; the hull had not been breached, and he thought he would be able to back the steamer off. However, when the engines were put in reverse, the ship didn’t budge. Pearce ordered the crew to move cargo from the fore hold and bring it aft. He also asked all the passengers to congregate on the stern. With the bow raised and the stern lowered, he hoped the ship would easily slide back off the reef. As the tide peaked, the engines were turning at maximum speed, but the vessel remained firmly stuck. The passengers and most of the crew retired for the night, expecting they would try again on the next high tide.

Meanwhile, the weather continued to deteriorate. A powerful storm was fast approaching over the northern horizon. Through the rest of the night, the Gothenburg was lashed by high seas, torrential rain, and a gale-force wind.The steamer bumped and ground on the hard coral until the hull sprang leaks and she began taking on water, a lot of water.

In just a few short hours, the situation became dire. Captain Pearce began preparations to abandon the ship, starting with the evacuation of women and children. It was now around 3 a.m., and pitch-black. Most of the passengers were already up on deck despite the atrocious weather. Few wished to remain in their cabins below.

Pearce only had four lifeboats at his disposal, but two of them were swept away before he could get a single passenger off the ship. The third boat, only partly filled with passengers, capsized and broke apart as soon as it was lowered into the water. Then the ship heeled over, and a mountainous wave swept many of the passengers from the deck to drown in the turbulent sea.

A lucky few managed to swim back to the ship and were rescued by those who had climbed into the ship’s rigging before the wave struck. There they clung, hoping to ride out the storm. James Fitzgerald, John Cleland, both passengers, and one of the crew, Robert Brazil, were among the survivors.

Fitzgerald would later recall, “We had seen illustrations of shipwrecks, but on this frightful morning … before daybreak, we saw the dreadful reality of its horrors. The ship was lying over on the port side, awfully listing, a hurricane was blowing, rain was coming down as it does in the tropics, and unmerciful breakers were rushing over the unfortunate vessel, seldom without taking some of the people with them.”

John Cleland, a gold miner returning to Adelaide, spotted the fourth lifeboat floating upside down, still attached to its davits. He knew that if they were to have any chance of survival, they needed that boat. He climbed down from the rigging, tied a rope around his waist and swam through the breaking waves to better secure it.

Cleland’s first attempt failed, and he swam back through the surging seas to the relative safety of the main mast. James Fitzgerald then joined him, and together they repeatedly swam out to the boat, cut away at the tangled mess of ropes, and then swam back to the mast to rest. Finally, they cut through the last of the ropes securing the boat to the davits. They then tied it off again with a length of rope attached to the mast. But the boat still floated upside down. They had been unable to right the craft on their own.

Seeing the pair struggling, Robert Brazil swam out and joined them, and with their combined weight, they were able to flip the lifeboat over. Cleland and the others were relieved to see that the oars were still securely locked in place.

The trio then returned to the mast and tied themselves to the rigging high above the waves. They stayed there all that day and the following night, tied to rigging so they would not fall when they dozed off. Then, the following morning, the weather began to ease.

The three men returned to the boat and bailed it out. Cleland, Fitzgerald, Brazil and eleven other men climbed into the lifeboat and eventually made it to the safety of Holbourne Island. They were rescued by boats sent out from Bowen to search for survivors the next day. Over one hundred people lost their lives in the disaster, Captain Pearce among them.

A marine board enquiry found that the captain had not exercised sufficient care in the navigation of his ship. They felt that had he made the effort to sight Cape Bowling Green lighthouse or Cape Upstart as he steamed south, he might have more accurately fixed his position, and the disaster could have been averted.

The full story of the Gothenburg shipwreck is told in A Treacherous Coast: Ten Tales of Shipwreck and Survival from Queensland Waters, available as a Kindle eBook or paperback through Amazon.

© Copyright C.J. Ison, Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2021.

Enter your email address below to be notified of new posts.