In November 1852 a migrant ship dropped anchor in Port Phillip Bay with some 700 passengers, many of them gravely ill. The 1,200-ton American Clipper Ticonderoga had been chartered to bring immigrants out to start a new life in Australia, but the three-month journey to their new home proved a nightmare for many of the mostly Scottish passengers.

Victoria was experiencing a labour shortage and had started offering assisted passage for workers to come and settle in the colony. Most of the passengers comprised of farmhands and their young families. But, not surprisingly, there was an incentive to get the most people out at the lowest cost to the Government.

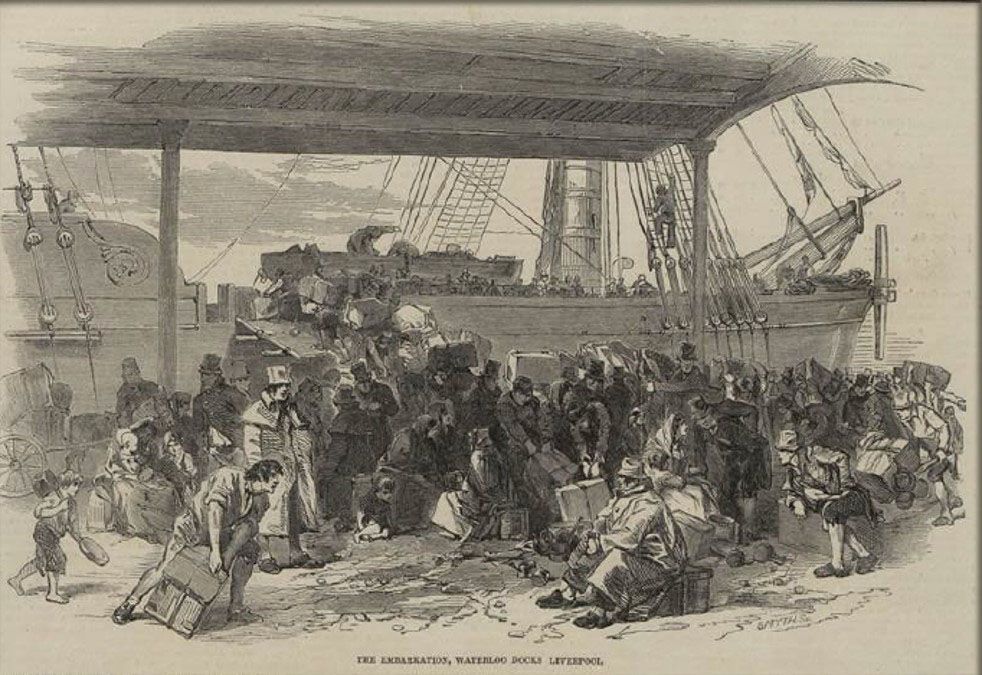

When the Ticonderoga left Liverpool she was overcrowded, even by the standards of Victorian England. Not long into the voyage passengers, many of them young children, started developing a red rash, high fever and sore throat. At the time the disease was sometimes called scarlet fever or Scarlatina, but it is generally thought today that it was Typhus that wreaked so much havoc on the passengers. Easily treated with antibiotics today, it had a devastating effect on those trapped onboard the ship.

It was impossible to separate the sick from the healthy passengers in the overcrowded, poorly ventilated and unsanitary passenger accommodation spread across two decks. Consequently, the disease spread unchecked.

Passengers died in such numbers that as many as ten would be bundled together into a sheet of canvas for burial at sea. By the time they reached the port city of Melbourne more than 100 people had lost their lives. Another 150 were sick and in desperate need of medical attention, for they had long run out of medical comforts and the ship’s surgeon had been felled by the disease while attending to his patients. Many of those, 82 to be precise, died in the days and weeks that followed.

The passengers and crew were quarantined at Point Nepean just inside the Port Phillip Bay heads for the newly formed Victorian Government had already earmarked a parcel of land there to build a quarantine station. Tents were hastily erected using spars and ship’s sails and two nearby houses owned by lime burners were used as makeshift hospitals and staffed with medical men brought out from Melbourne. A ship was also dispatched to the Quarantine Station to serve as a hospital for the more serious cases.

The quick response contained the highly infectious disease and kept it from spreading to the general population. By January 1853 the epidemic had run its course. The surviving passengers were taken to Melbourne and the Ticonderoga was released to go on its way but not before being thoroughly fumigated.

The Emigration Commissioners who had chartered the ship in the first place were roundly condemned for allowing so many migrants, especially families with young children, to be sent out in such unhealthy conditions. The Ticonderoga was just the last and worst of several recent migrant ships coming to Australia to suffer such an appalling loss of life.

Between the Bourneuf, the Wanota, Marco Polo, and Ticonderoga, 279 passengers had died at sea as a result of infectious diseases on the passage out to Melbourne. The lesson was learned and future migrant ships were reduced to carrying no more than 350 passengers.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.