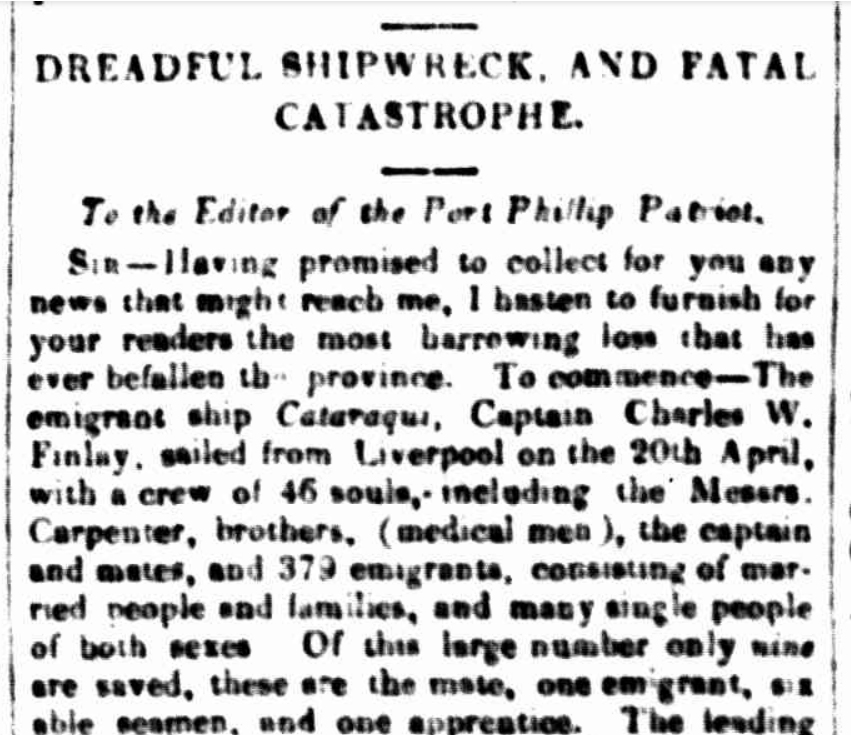

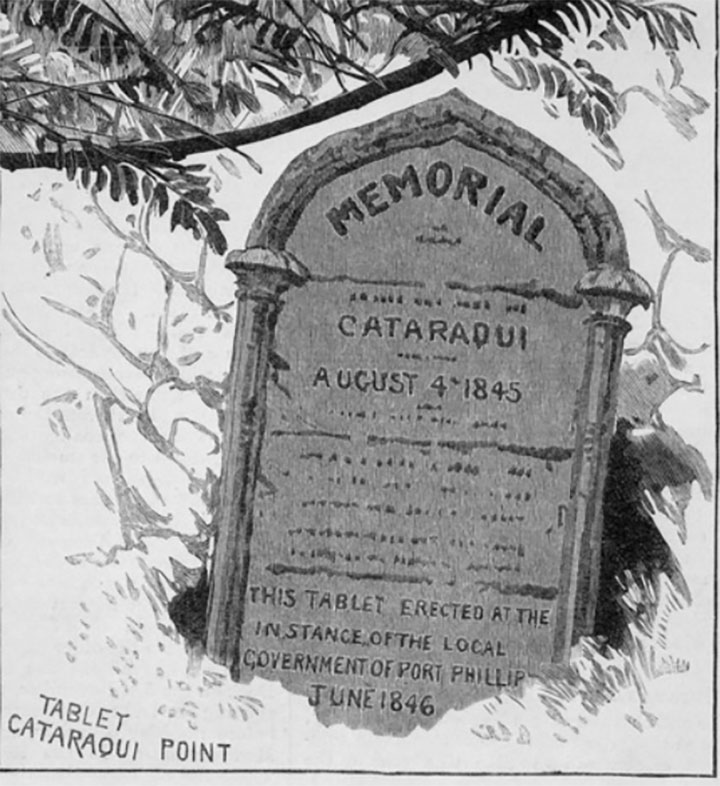

Australia’s worst shipwreck occurred off King Island on 4 August 1845. The 803-ton barque Cataraqui, carrying 409 people, slammed into rocks during foul weather. Only nine people made it ashore alive.

The Cataraqui sailed from Liverpool on 20 April, carrying 366 assisted migrants who were escaping poverty in England, and hoping to make a better life for themselves in Australia. Many of the passengers were women and children accompanying their menfolk, who had been guaranteed employment in the labour-strapped colonies.

The voyage had largely been uneventful until they were passing to the south of St Paul’s Island about halfway between the Cape of Good Hope and Australia’s west coast. On 15 July, the ship was struck by powerful winds and mountainous seas. For the next fortnight, there was no respite from the atrocious weather, as they steadily pushed east along the 40th parallel. They are not called the “Roaring Forties” for nothing.

By Sunday, 3 August, the Cataraqui was only one or two days’ sailing away from Melbourne and still the strong winds and high seas had not abated. At 7 p.m., Captain Charles Finlay estimated their position at 39° 17’S 141° 22’E or about 100 kilometres south of Cape Nelson on the Victorian coast. By 3 o’clock the next morning, the wind had begun to ease, and Captain Finlay bore northeast, expecting the distinctive profile of Cape Otway to come into view off his port bow. That would have given Finlay his first accurate position since passing St Paul.

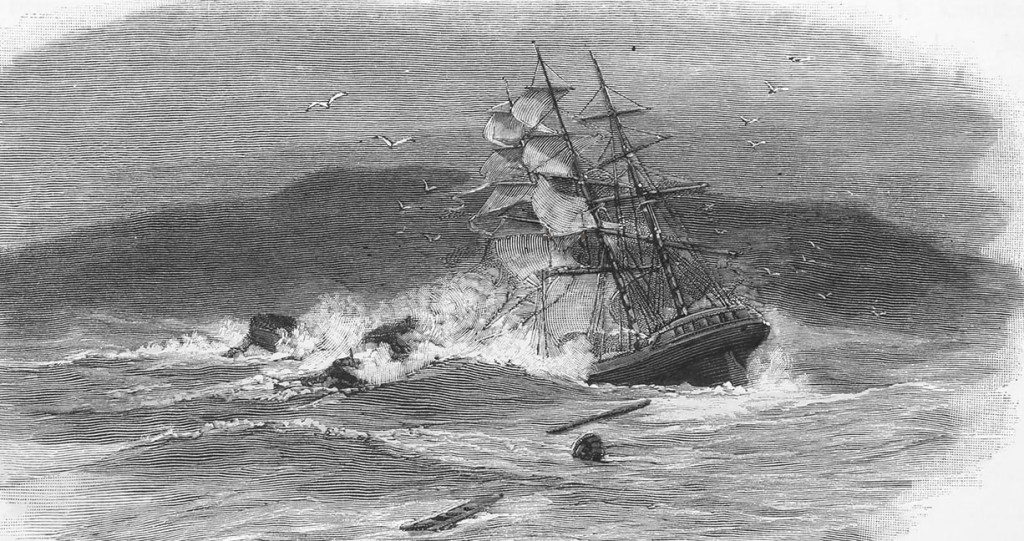

Unfortunately, the strong winds had pushed the Cataraqui along faster than he had calculated. Unbeknown to him, his ship was further east and further south than he realised. So, rather than making towards Cape Otway with deep water ahead, the ship was heading towards the rugged west coast of King Island, hidden behind a blanket of thick weather and inky darkness.

At 4.30 a.m., the ship struck rocks near Fitzmaurice Bay. First Mate Thomas Guthrie provides a harrowing account of those first few hours, which was published in the Port Phillip Patriot on 14 September 1845.

“Imagine 425 [actually 409] souls,” he began, “of which the greater part were women and children, being suddenly awakened from a sound sleep by the crashing of the timbers of the ship against the rocks. The scene was dreadful, the sea pouring over the vessel—the planks and timbers crashing and breaking—the waters rushing in from below, and pouring down from above—the raging of the wind in the rigging and the boiling and hissing of the sea—joined to the dreadful shrieks of the females and children, who were drowning between decks.”

“The attempts of so many at once to get up the hatchways blocked them up, so that few got on deck uninjured, and when there, the roaring noise, and sweeping force of the sea was most appalling. Death stared them in the face in many forms— for it was not simply drowning, but violent dashing against the rocks which studded the waves between the vessel and the shore.”

“When day broke, they trusted to find a way to the shore, but no, the raging waves and pointed rocks rendered every attempt useless. The sea broke over the vessel very heavily, and soon swept away the long boat and almost everything on deck.”

In those few desperate hours, it was estimated that some 200 people lost their lives. Another 200 were faced with the stark reality that, even though the land was tantalisingly close, there was no safe way to reach it. The ship had struck a rocky reef running parallel with and a short distance from the coast. Captain Finlay ordered the masts cut away. He hoped the powerful waves might then carry the lightened ship over the rocks and closer to shore, where the survivors might stand some chance of reaching land. Unfortunately, it had no effect. The ship remained firmly stuck on the jagged rocks. Finlay then tried floating a buoy ashore, but the rope became entangled in kelp long before it could be used as a lifeline.

Around mid-morning, Captain Finlay ordered their only surviving boat over the side. He, the boatswain, the ship’s surgeon and four seamen set off in her in a desperate attempt to get a line ashore. However, the boat overturned in the tumultuous seas. Finlay was the only one to make it back to the ship alive.

At midday, the Cataraqui broke amidships and the aft sank, taking about 100 terrified people with it. By now, there were only 90 people still clinging to the wreckage. By midnight, 12 hours later, they were down to 50. Overcome by fatigue and the freezing cold, one survivor after another dropped from the wreck into the raging sea.

Thomas Guthrie clung on for as long as he could. But then he was finally swept from the last vestige of the wreck as it sank below the surface. Somehow, he avoided being dashed against the rocks, and the surf deposited him on the beach to join eight other survivors. One was Solomon Brown, a 30-year-old labourer who had joined the ship with his wife and four daughters. He was the only passenger to make it off the ship alive. The other seven, like Guthrie, were members of the crew.

The next day, on 6 August, the survivors were discovered by a party of sealers. Likely alerted by the debris being washed ashore near their camp, they had gone to investigate. Finding the nine survivors in a desperate state, the sealers built a shelter for them, started a fire, and fed them with provisions brought over from their own camp. Guthrie and the other Cataraqui survivors stayed with the sealers for four weeks. On 7 September, the cutter Midge arrived with fresh provisions. When she returned to Melbourne with a cargo of seal and wallaby skins, the survivors went with her.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2023.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.