On the night of 12-13 August 1856, the French Naval steam corvette Duroc was wrecked on Mellish Reef about 800 km off the Queensland coast. After the ship ran aground, her passengers and crew, numbering 70 people, made it onto a small sand cay where they were safe for the time being. However, they were stranded far from regular shipping channels, and the chance of their being rescued was remote. Captain Vissiere thought their only chance of getting off the islet was to build a new boat from the wreckage of the old.

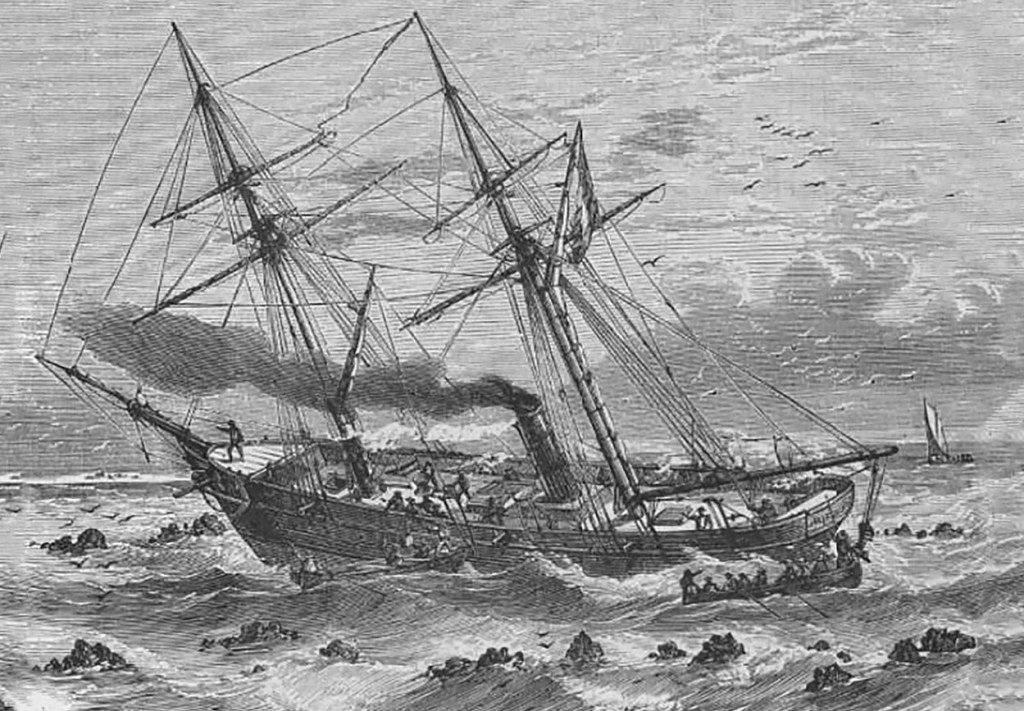

The Duroc had set off from Port de France (Noumea), New Caledonia, five days earlier, but on that night she ran aground on a submerged coral reef and could not get off. Each passing swell pounded the hull onto the reef, and she began taking on water. Fearing the ship might break apart during the night, Captain Vissiere ordered the crew to start bringing all stores, provisions, and water casks up on deck. He also had the four lifeboats prepared in case they had to abandon ship during the night. Then Vissiere had an anxious wait until morning, when he could better assess their situation.

Daylight revealed the ship was well and truly lodged on the reef, and they were surrounded by breaking seas. But about four kilometres away, there was a small, low-lying sandy islet which seemed to offer a place of refuge. So began the laborious task of ferrying all the ship’s stores and personnel to dry land. Over the next 10 days, they stripped the Duroc of its masts, bowsprit, sails, spars, blacksmith’s forge, a water distillation plant and the cook’s oven. By 23 August, they had emptied the stranded vessel of anything useful and established a comfortable camp on the tiny cay. Captain Vissiere was satisfied that their immediate survival was assured, but they were stranded nearly 800 km from the nearest land, and rescue seemed unlikely.

Vissiere prided himself on being a competent master mariner, and he could not account for how his ship had run aground. He took several unhurried astrological observations on the island and would later claim that the reef he had struck was, in fact, some distance from where it was laid down on his chart. Feeling vindicated, the captain then turned his mind to finding a way back to civilisation, for not only was he responsible for his crew, but his wife and baby daughter accompanied him.

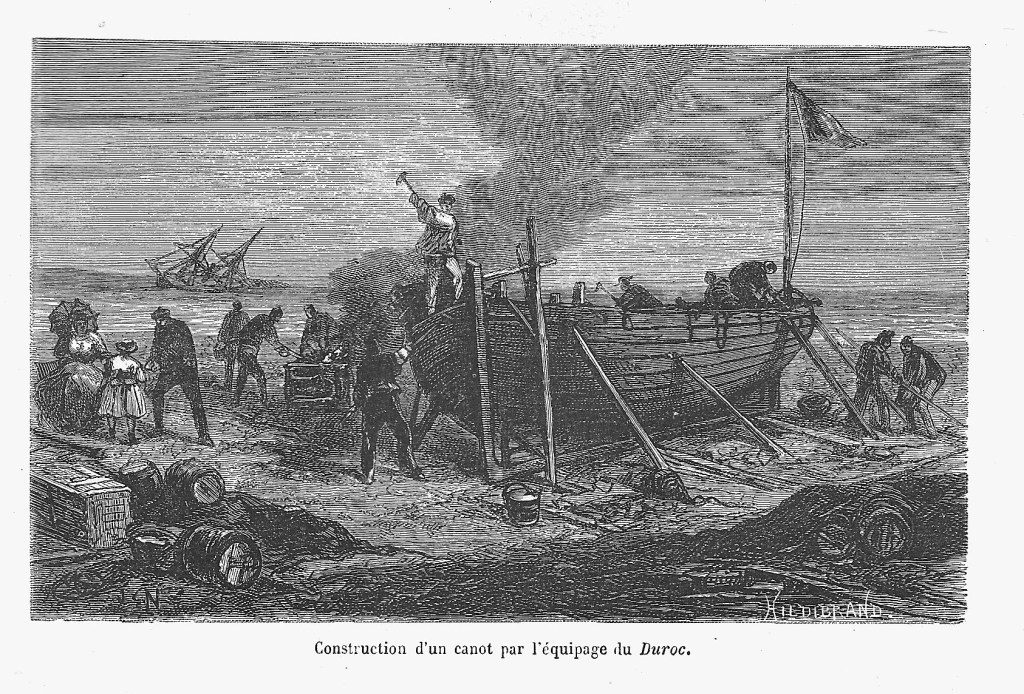

Captain Vissiere felt that his best course of action would be to make for Australia’s east coast, where he could expect to find help from a passing ship. However, the lifeboats could carry only a fraction of those stranded on the small island. So, Captain Vissiere opted to send his First Mate, Lieutenant Vaisseau, off with the three largest boats and about half the crew. He would remain on the island with his wife, daughter, and about 30 others. They would construct a new vessel from the timber they had salvaged from the Duroc and make their escape if no one had come for them in the interim.

The three boats set off on 25 August with instructions to make for Cape Tribulation, where, with any luck, they would meet a British ship sailing the Great Barrier Reef’s inner passage. Cape Tribulation was probably chosen because it was easily recognisable and it was where the reef pinched in close to the coast, funnelling any passing ships close to land.

After setting off from Mellish Reef, the three boats encountered rough weather, which threatened to capsize the heavily overloaded craft. Lt Vaisseau tried tethering the three boats together so they would not become separated, but in the rough seas, this proved dangerous, and the lines were cut. After weathering the conditions for two days, Vaisseau decided they should jettison everything non-essential to lighten the load and raise their freeboard.

Then, one day, while Lt Vaisseau was taking his noon observation, his boat was struck by a rogue wave, tossing him into the sea. Unable to swim against the current to make it back on board his lifeboat, he would have drowned had another boat trailing astern not been able to come close enough to rescue him. Vaisseau had a lucky escape, for he was only plucked from the water as his strength was beginning to fail him.

After five days at sea, on the evening of 30 August, they crossed through the Great Barrier Reef near Cape Tribulation and anchored in calm waters for the night. The men thought the worst of the ordeal was behind them, and they would soon fall in with a passing ship. Lt Vaisseau noted they still had 72 kgs of sea biscuits, 20 litres of brandy and 60 litres of wine when they reached the Australian coast. However, shared among 36 hungry men, that would last them only another few days.

The next day, they made land, filled their water casks, and then bore north, hugging the shore, pushed along by the prevailing southerly winds. They stopped each night in the lee of islands, foraged for roots, greens and shellfish, and cast out lines hoping to catch fish. They only delved into the supply of sea biscuits when their efforts failed to find enough food.

By 9 September, they had reached Albany Island in the Torres Strait. They continued sailing past Booby Island, unaware that there was an emergency store of food and water there to aid shipwrecked sailors. Having sighted not a single ship while off the Australian coast, they ventured out into the Arafura Sea. Lt Vaisseau decided they should head for the Dutch settlement of Kupang on Timor Island. The three boats finally arrived on the evening of 22 September, and not a moment too soon, for their food had run out several days earlier.

Meanwhile, Captain Vissiere and the remaining men had been kept busy constructing the new vessel, which they named La Deliverance. Under the directions from the ship’s master carpenter, they sawed the Duroc’s lower masts into planks and fixed them to a frame. The new craft measured 14 metres in length and was completed around the time Lt Vaisseau and his party reached Timor Island.

On 2 October, La Deliverance was launched, and they sailed away from the island they had called home for the past six weeks. Captain Vissiere intended to make for the Australian mainland, just as his lieutenant and the three boats had done. Once off land, he would decide whether they should head north, through Torres Strait and on to Kupang, or turn south towards Port Curtis (Gladstone), which was the most northerly settlement on the east coast at the time. When he reached the Australian coast, he found the same southerly trade winds that Lt Vaisseau had.

Despite the seemingly optimistic start, the passage was arduous, hampered as it was by unpredictable weather. Prolonged calms left them stranded for days at a time. The doldrums were only relieved by violent storms that lashed them mercilessly and threatened the safety of the vessel. By the time they were rounding Cape York, the boat was leaking alarmingly. Captain Vissiere pulled in at Albany Island so urgent repairs could be made before they left the relative safety of the Australian mainland. Once the leaks were plugged, they got underway, ready to cross the Arafura Sea. On 30 October, four weeks after setting off from Mellish Reef, La Deliverance sailed into Kupang harbour.

Though they suffered greatly during the ordeal, Captain Vissiere did not lose a single person as a result of the wreck or the 4000 km voyages undertaken by the survivors to reach Kupang.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2023.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.