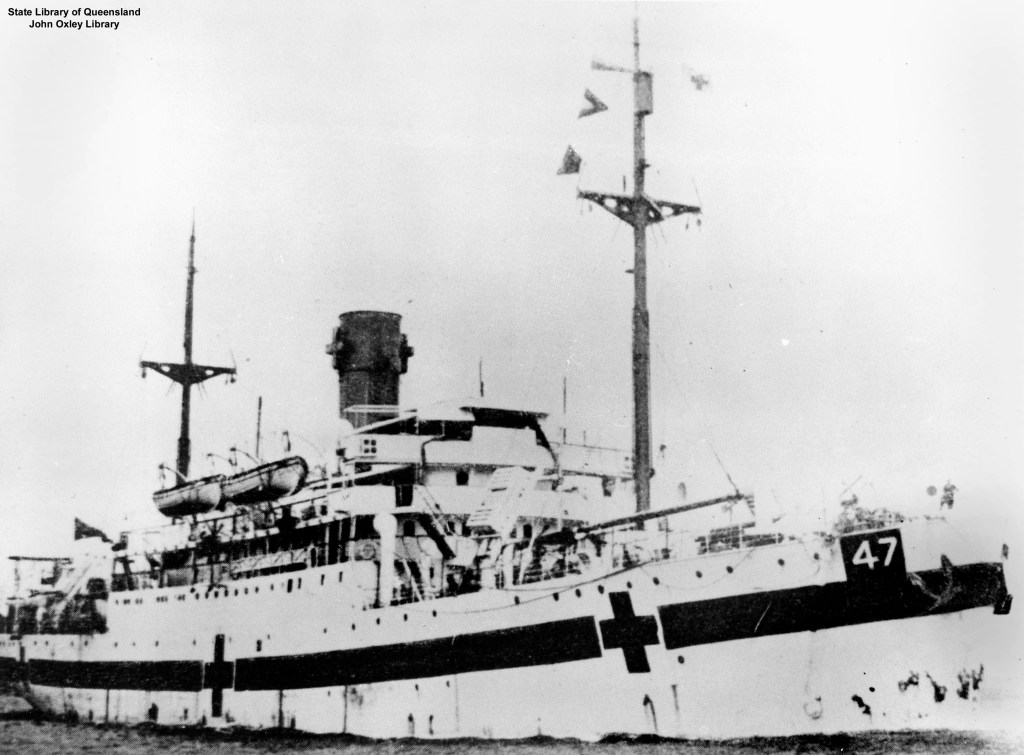

On a quiet Saturday afternoon on 15 May 1943, the senior Royal Australian Naval officer in Brisbane received a message reporting that a USN destroyer had picked up survivors from the Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Centaur. This was the first anyone knew of the tragedy that had unfolded a short distance off the Queensland coast.

The Centaur left Sydney bound for Port Moresby to pick up sick and wounded diggers and return them to Australia. Fighting had been raging in New Guinea for over a year, and casualties had been high. As she steamed north this time, she had a full crew, and she was also delivering members of the 2/14th Field Ambulance to Port Moresby. In all, there were 332 souls on board.

Around 4 a.m. on Friday, 14 May, the Centaur was about 30 nm (55 km) off Moreton Island when she was struck by a torpedo fired by a Japanese submarine. Merchant seaman Alfred Ramage had just finished his watch and was climbing into his bunk when he was rocked by the powerful explosion. Ramage immediately knew what had happened, so he quickly donned his lifebelt and began making his way to the boat deck. Urgency spurred him along, for he had never learned to swim.

The torpedo had hit the portside fuel bunker, which sent flames ripping through the ship, burning and trapping many people below decks. Those same flames soon engulfed the boat deck and then the bridge as the crew struggled to get the lifeboats away. Steward Frank Drust was standing outside the ship’s pantry when the floor collapsed and a wall of flames separated him from the closest companionway leading to the deck. By now, the Centaur was sinking by the bow. He waded through swirling waist-deep water and eventually made it onto the deck. He and a few comrades began throwing hatch covers and life rafts over the side to help those already floundering in the water. They continued their efforts until they, too, were washed off their feet as the sea rose around them.

Sister Ellen Savage, one of 12 nurses on board, was woken by the loud explosion reverberating through the ship. She and fellow nurse Merle Morton fled their cabin in their pyjamas and were told by their commanding officer to get topside as quickly as they could. They had no time to retrieve warm clothing or anything else from their cabin before they took flight.

By the time they reached the deck, the Centaur was already sinking. The suction dragged Ellen Savage down into a maelstrom of whirling metal and timber, cracking her ribs, breaking her nose and bruising her all over. But suddenly, she found herself back on the surface in the middle of a thick oil slick. She never saw her cabinmate or her commanding officer again.

Savage could see a large piece of wreckage a short distance away and swam for it. It turned out to be a portion of the ship’s wheelhouse where several others had already taken refuge. In time, as many as 30 survivors climbed onto the fragile floating island. Others who had escaped the ship kept themselves afloat on pieces of debris or the few rubber liferafts that had been deployed in the hectic minutes after the torpedo struck.

Ship’s cook Frank Martin survived by clinging to a single floating timber spar. For the next 36 hours he held on for dear life, half-naked and nothing to eat or drink until he was plucked from the water.

Seaman Matthew Morris was a little luckier. At first, he found himself alone in the water, blinded by salt and oil. But when his vision returned, he spied a small raft a short distance away, so he swam over and climbed into it. Then he spotted his mate, Walter Tierney, and hauled him onboard. As daylight came, the pair saw something floating in the distance and paddled towards it. It turned out to be the wheelhouse, so they lashed their raft to it and joined the 30 or so people already there.

The survivors spent all that day huddled on the makeshift raft. There was less than 10 litres of water on hand, and that was doled out sparingly. Several of the survivors had severe burns to their bodies. One was Captain Salt, a pilot from the Torres Strait Pilot Service, who had run through a wall of flame to escape the sinking ship. Despite his painful injuries, he kept morale up, reassuring everyone that help would soon be on the way.

Matthew Morris led choruses of “Roll out the Barrel,” “Waltzing Matilda,” and other wartime favourites to keep people from thinking about their plight. Sister Savage tended to the wounded with what little she had on hand, never complaining of her own injuries. She kept her broken ribs to herself until after they had all been rescued.

One poor man, Private Jack Walder, had been badly burned. He drifted in and out of consciousness until he passed away on the raft. Savage prayed over his body before it was gently pushed away to sink from sight.

According to several survivors, sharks were constant and unwelcome companions, circling as they clung to wreckage or perched precariously on makeshift rafts.

The survivors spent all of Friday, Friday night and Saturday morning hoping and praying that they would soon be rescued. Several said they heard aircraft flying overhead or saw ships passing in the distance, but the Centaur survivors went undiscovered. At one stage, those on the wheelhouse considered dispatching one of the rubber rafts to try to make landfall to raise the alarm. However, that idea was eventually discarded when it was decided that the chances of surviving the large ocean swells in the small craft were unlikely. On Friday night, the Japanese submarine surfaced briefly near the wheelhouse, sending a chill through the survivors. Everyone remained quiet, and a short time later, the sub disappeared below the waves again. The survivors never gave up hope of being rescued. Then, on Saturday afternoon, an Australian Air Force aircraft on a routine flight saw something strange floating in the water. On investigation, the pilot realised it was wreckage and guided the US Navy destroyer, USS Mugford, to the location. They quickly began searching the surrounding waters for more survivors.

In all, 64 people were saved, but another 268 were not so lucky. Sister Ellen Savage was awarded the George Medal for her devotion to duty, tending to the wounded despite her own injuries.

Lest We Forget.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2023.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.