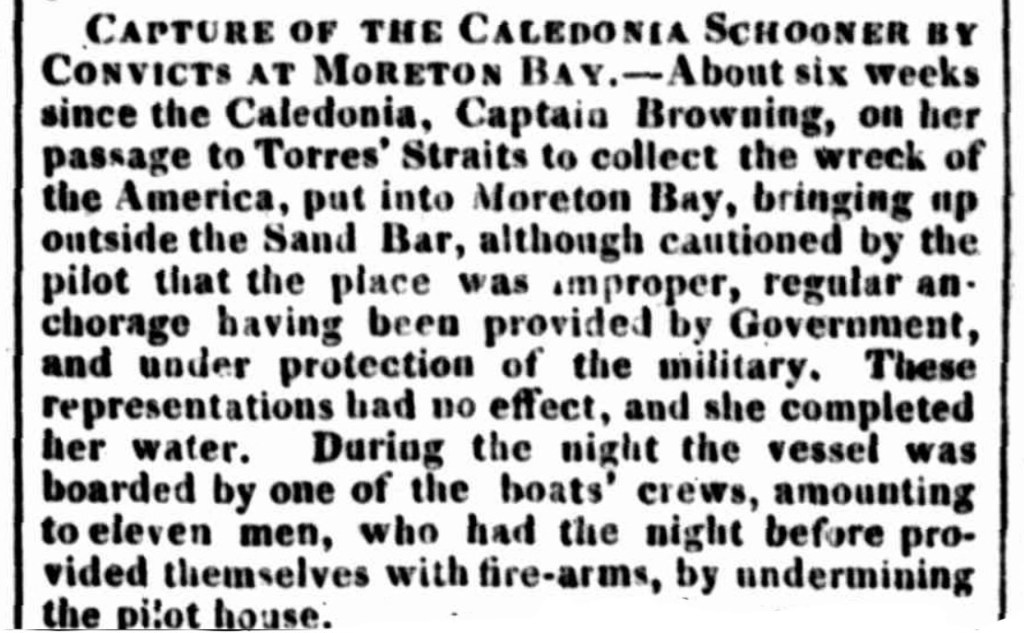

In 1845 the trading schooner Ariel was seized off the coast of China while carrying a valuable cargo worth millions of dollars in today’s money. This act of piracy was unusual because it was not carried out by a band of desperate cutthroats but by two of the ship’s own officers.

The schooner Ariel was owned by the powerful trading company Jardine Matheson and was a fast-sailing coastal merchant vessel, probably around the 100-ton class. She was also well-armed with cannons to ward off marauders in those dangerous waters. The Ariel was crewed by British officers comprising the captain, first mate, and gunner. The only other Englishman on board being a young apprentice. The sailing crew were all Filipino, or “Manila men” as they were called at the time. A young Chinese woman was also on board who was likely the captain’s mistress although she was variously described as his cook or cabin steward.

The Ariel regularly cruised between Chinese ports carrying all manner of goods. This time she was sailing from Xiamen (then called Amoy) bound for Hong Kong with a very valuable cargo. One account had the ship carrying $100,000 in Spanish silver Reales, the currency of trade at the time. Another had her carrying a shipment of opium plus a quantity of gold and silver coin. Either way, the value of the cargo was substantial, probably equivalent to many millions of dollars today, and it proved a temptation too irresistible to the mate and gunner.

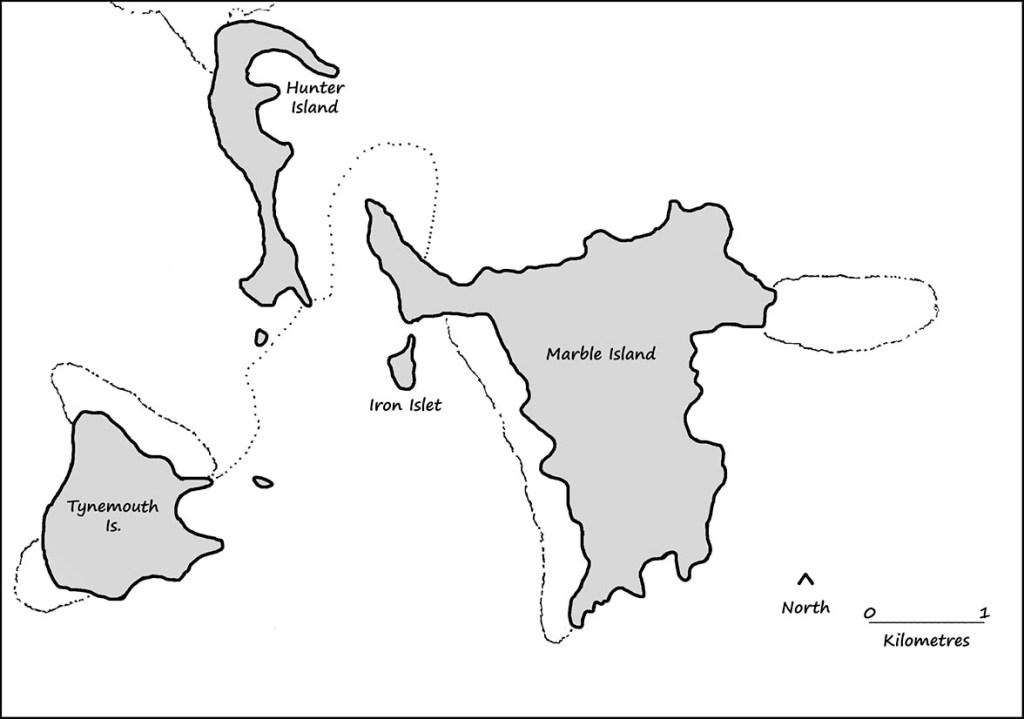

The evening they sailed from Xiamen, Wilkinson, the first mate, called Captain Macfarlane to come up from his cabin. They were now off Nan’ao Island 160kms south of Xiamen and about one-third of the way through their passage to Hong Kong. When Macfarlane came on deck he was confronted by Wilkinson and the gunner both armed with cutlass and pistols. Wilkinson told Macfarlane they had seized the ship and they would be making for Singapore. The pair offered to make Macfarlane an equal partner in their crime, for there were more than enough riches to go around. But the captain refused to have any part in it and tried to persuade the men to give up their brazen heist.

Meanwhile, the crew was gathered on the forecastle and though they appeared not to be participating in the mutiny, Wilkinson said they were on his side. The threat was obvious. Captain Macfarlane was on his own. Macfarlane was locked in his cabin with the assurance he would be released unharmed as long as he did nothing to disrupt their plans.

The next morning the captain asked to be let go in the longboat but the mate refused, telling him they were too close to Hong Kong and he would not risk capture should the captain raise the alarm before they were well out to sea. A little later the Chinese girl went forward and spoke with the Filipino crew and learned they wanted nothing to do with the mutiny. They armed themselves with knives and the cannon’s ramrods on the captain’s command and attacked the mate and gunner. Meanwhile, several men smashed open the cabin skylight to rescue the captain.

By the time Macfarlane was hauled out through the skylight, the mate was lying bashed, stabbed, and bleeding to death on the deck while the gunner had taken refuge in the cabin just vacated by the captain.

Captain Macfarlane, now back in command of his ship, found a fowling piece (shotgun) belonging to the gunner and ordered him to surrender. When the gunner opened the hatch leading to the ship’s gunpowder magazine and threatened to blow everything up, Macfarlane shot him in the leg. He was then quickly overpowered and taken to Hong Kong to stand trial. Wilkinson died from his wounds before they reached port. The gunner, whose name is not recorded, was found guilty of piracy and sentenced to transportation for life.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blog posts, please enter your email address below.