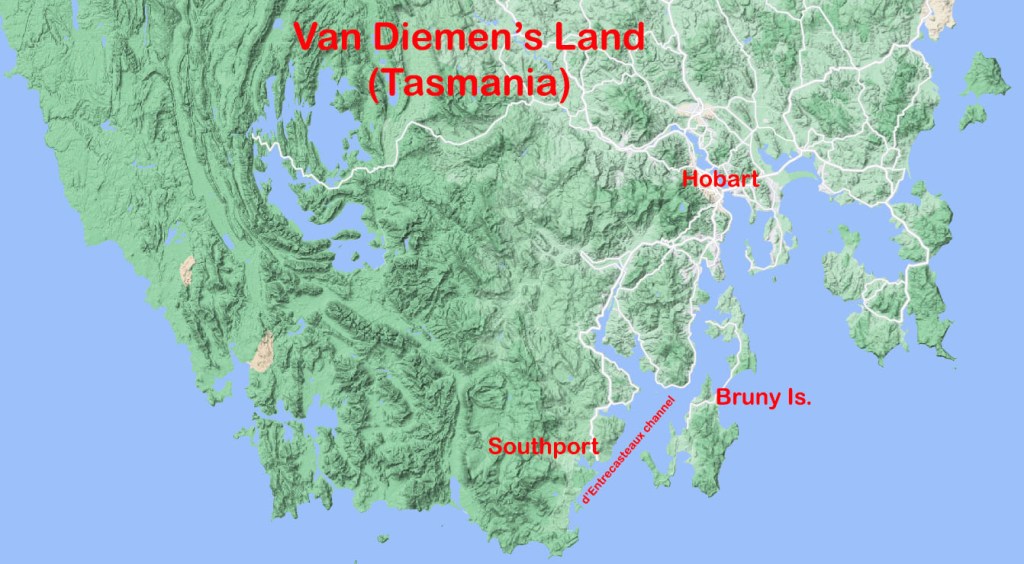

In September 1894 the 1600-ton iron barque Cambus Wallace ran aground on Stradbroke Island spilling its cargo of salt, Scottish whiskey and dynamite to be strewn along the beach. Six seamen lost their lives in the tragedy and the wreck may also have contributed to the island splitting in two.

The Cambus Wallace had sailed from Glasgow four months earlier on her maiden voyage and had experienced more than her fair share of bad weather on the passage out. As she made their way up the Australian coast the crew battled strong winds, high seas and heavy rain. Then, around 5 o’clock on the morning of 3 September, disaster struck when they were only hours away from reaching their destination at Moreton Bay.

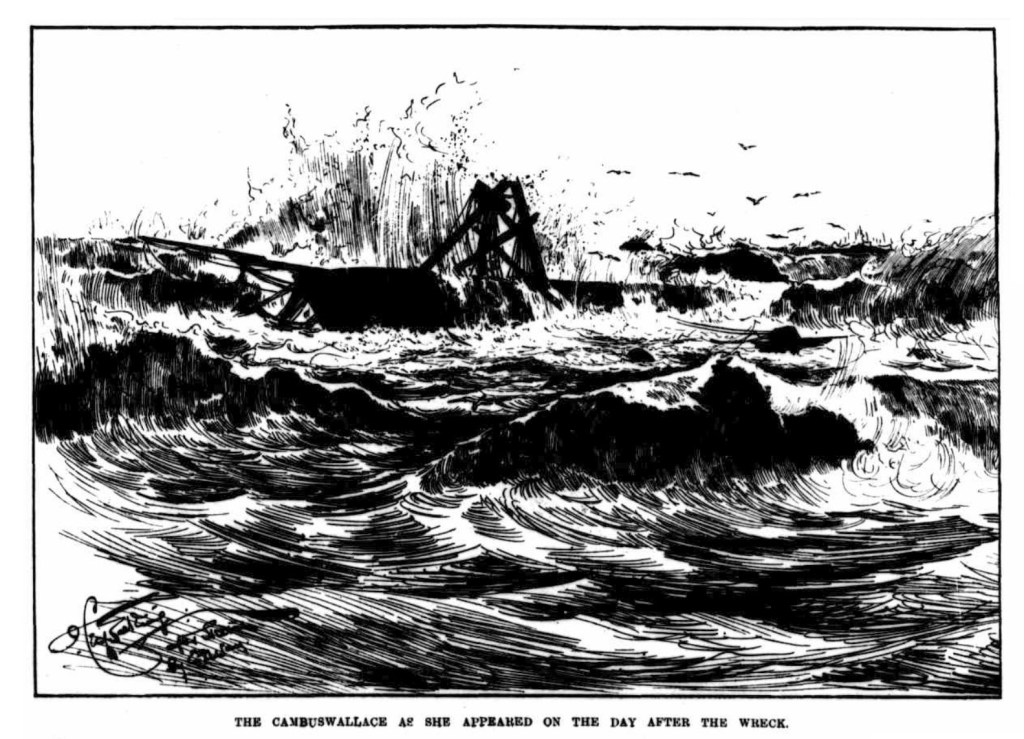

Lookouts had been posted but they were of little help in the thick weather. By the time someone saw breaking waves ahead, it was too late to avoid catastrophe. The ship struck sand near Jumpinpin and came to a halt broadside to the seas about 200m from the beach. Powerful waves swept over the stranded vessel washing away two lifeboats. They had lost a third during an earlier bout of rough weather.

There were 27 men on board, and they were now down to just a single lifeboat but the conditions were far too dangerous to launch it. Most of the crew took shelter on the poop, while Captain Leggat and several others climbed into the mizzen mast rigging. The steward chose to remain in his cabin and wait for help. He paid for that poor decision with his life.

Two young seamen tried to swim a line across to the beach, so tantalisingly close, to help the rest of the men pull themselves to safety. But the roiling seas and white water made for a dangerous crossing. One of the men ran into difficulties and was pulled back to the ship by the line tied around his waist. A Swedish sailor, Gustav Kindmark, reached land but without a line, he could do nothing but go in search of help.

Meanwhile, the situation on the barque became dire. Below decks were awash with water. Around midday, the First Mate was swept off the ship but he was able to make it to shore, albeit somewhat battered and bruised. Captain Leggat was knocked from his perch by falling debris but managed to get back into the rigging before he was washed overboard. It was clear they could not wait any longer for help to arrive. The ship was beginning to break up.

Captain Leggat tried again to lower their last lifeboat. This time they got it into the water. The carpenter was washed off the deck and drowned while waiting to board the boat. One of the apprentices was also swept away but he was able to swim to shore. The cook drowned after he tried to jump into the boat but missed. Several others dove into the sea and swam towards land. The captain was the last to leave the ship. With the swing of an axe, he cut the rope holding the lifeboat fast and they headed towards the beach.

In all, 22 men made it ashore alive but one older seaman died a short time later as a result of the ordeal. Kindermark returned to the beach with several fishermen he had found on the sheltered side of the island and they erected tents to provide shelter for the near-naked survivors.

As the ship broke apart cargo began washing ashore. Among the debris were cases of whiskey and other liquor as well as several hundred boxes of dynamite. A customs officer from Brisbane had the unenviable task of preventing the “duty free” spirits from falling into the hands of local fishermen and boaties drawn to the bounty on offer. But perhaps, of greater concern were the boxes of water-damaged high explosives littering the beach.

A decision was made to gather the dynamite and blow it up in place. The explosions were so violent they reportedly shook houses and shattered windows 20 kilometres away. An eyewitness to one of the detonations claimed sand was blown high into the air to fall like a “heavy show of rain” into the bay on the lee side of the Island.

During a particularly high tide four months later, the sea washed over the island at its narrowest point which also happened to be where the Cambus Wallace had been wrecked and the dynamite disposed of. Then during a powerful storm in May 1898 a deep channel 650m wide was cut right across the island and washed away the graves of the six seamen who had been buried there after the shipwreck. While it is possible the channel might have formed anyway, it is also conceivable the massive explosions on the narrow strip of sand contributed to its breaching. The channel separates North and South Stradbroke Islands to this day.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.