On 2 March 1899, Cyclone Mahina formed near the Solomon Islands and began tracking south-west towards the Queensland coast. On the same day, a second weather system formed in the Arafura Sea northwest of Darwin. This “monsoonal disturbance” was named Nachon and began moving towards the southwest. Unbeknown to the Thursday Island pearling fleet anchored in Bathurst Bay, 400 kilometres down the Queensland coast, both of these powerful weather systems were bearing down on them. Mahina and Nachon would collide over Bathurst Bay, wreaking havoc on the fleet, resulting in the loss of as many as 400 lives.

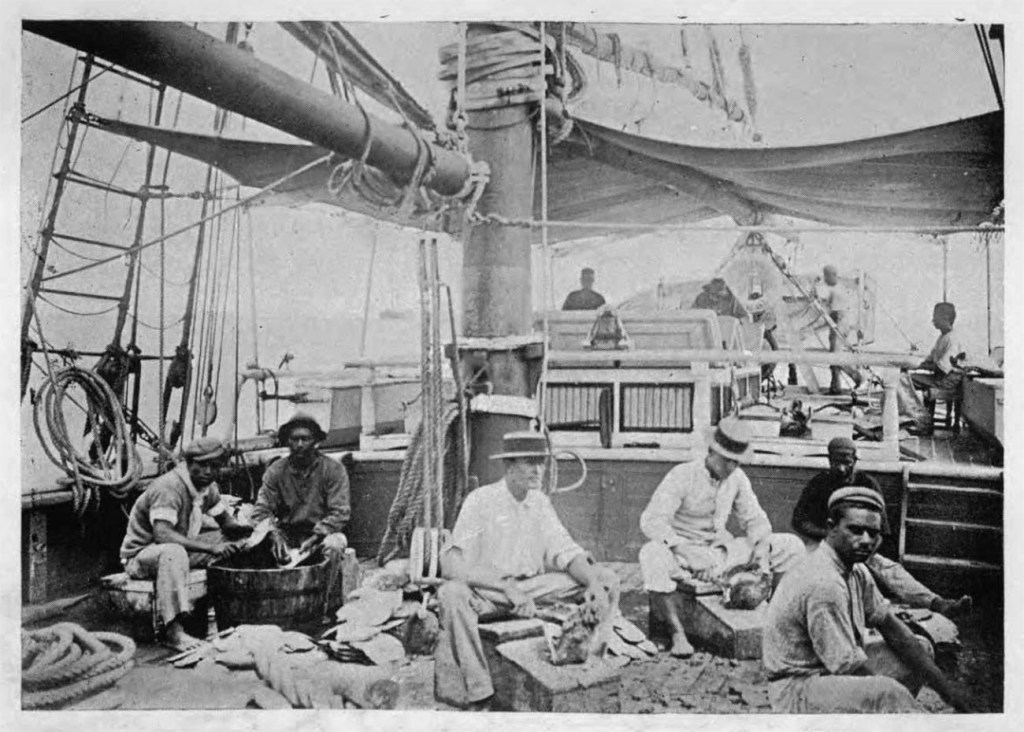

The pearling fleet was based at Thursday Island in Torres Strait, but the pearlers regularly ventured across Queensland’s warm tropical waters in search of shells. Pearling schooners served as floating processing stations for their fleet of ten to 15 luggers and diving boats. It was those smaller vessels that ranged out over nearby reefs, collecting the lucrative shells from the sea floor.

March 4 was a Saturday and, for the pearlers, the much-anticipated start to the weekend. After they had delivered their pearl shells to their respective station schooner, tending to any repairs and restocking with provisions for the next week, it was time to relax and catch up with friends and family whom they had not seen all week.

The schooners Sagitta, Silvery Wave, and Crest of the Wave were anchored near Cape Melville just inside Bathurst Bay. As the prevailing winds had been blowing from the southeast for the previous three weeks, everyone was anchored close to shore where the mountains extending inland protected them from the worst of the wind.

The schooners Tarawa, Meg Merrilees, Olive and Aladin were anchored about 75 kilometres away near Pelican Island on the northwestern end of Princess Charlotte Bay. The manned Channel Rock lightship and several other pearling vessels were scattered along the Great Barrier Reef in the path of the approaching storm. No one, including the local Aboriginal people, could imagine the violent mayhem about to be unleashed upon them.

At 7 o’clock on Saturday evening, only a moderate breeze was blowing from the southeast. However, just four hours later, the wind had increased to hurricane strength. It had also begun shifting direction from the southeast to the southwest. As Cyclone Mahina tore towards Bathurst Bay, the wind continued shifting further to the west, and eventually it blew from the northwest. For much of the early hours of Sunday, 5 March, the pearling fleet was exposed to the cyclone’s full fury. Torrential rain lashed the vessels. Streaks of angry lightning arced across the night sky while peals of thunder, howling wind and crashing waves competed to drown each other out. The hundreds of men and women trapped on their boats could do nothing but pray that they survived the ordeal.

Then, around 4 a.m., a massive storm surge swept through the bay. By 10 o’clock on Sunday morning, the tempest had moved inland, and some sanity returned to the world. It was only then that the few survivors would learn the full devastating impact of the storm.

The Tarawa’s anchor cables had parted around 3 a.m., and she was swept onto Pelican Island. However, she was lucky for the damage would be easily patched, and she would limp back to Thursday Island. The Meg Merrilees dragged her anchors and ran onto a coral reef. All hands survived the wild night, but attempts to refloat the schooner were unsuccessful. The tender Weiwera was also lost. Of the 30 or so luggers anchored nearby, one-third sank with the loss of nine lives. The schooners Olive and the Aladin were more fortunate. Their anchors held, and they survived the night.

The vessels lying off Cape Melville fared far worse. The 25-ton tender Admiral had only arrived in Bathurst Bay on the morning of the cyclone. She foundered at the storm’s height with the loss of her five crew and an unknown number of passengers brought down from Thursday Island to join the fleet. The Silvery Wave likewise was lost. Only a Japanese crew member named Sugimoto survived. The Sagitta was thought to have collided with the Silvery Wave and went to the bottom of Bathurst Bay with nearly 20 hands.

Captain W. Field Porter survived to give a harrowing account of that terrible night. He recounted that his schooner, Crest of the Wave, was anchored near the other vessels off Cape Melville while about 40 luggers were in shallower water close to the beach. As the storm intensified, his anchors began dragging. Fortunately, the wind and current pushed the schooner into deeper water. “The intense darkness and driving rain prevented anything [from] being seen of the other boats or the land. The sea by this time was very rough, and enormous waves broke time after time on board,” Porter later wrote of his experience.

The eye of the cyclone passed over his ship around 4.30 in the morning. After ten or fifteen minutes of dead calm, Captain Porter recalled, the wind suddenly came from the north-west, “with such terrific force that the schooner was thrown on her beam ends and [was] almost buried in the raging sea.” With much difficulty, the masts were cut away, and the ship righted itself. But by then, she had taken on a lot of water. The bilge pump was manned, and every spare hand bailed with buckets to keep the ship from sinking. Eventually, it was discovered that the water was entering through the rudder trunk. The leak was plugged with blankets and bags of flour, and the ship was saved. However, for 12 long and terrifying hours, the crew battled the elements, not knowing if each moment would be their last. Finally, the wind and seas started to ease, and Captain Porter and his men began to think they might just survive. As for the luggers, they either foundered at their anchorage or were driven ashore, where most were smashed to pieces. Some wreckage was found almost half a kilometre from the beach, taken there by the massive storm surge which swept several kilometres inland in places. Only a handful of the luggers were able to be refloated.

The Channel Rock Lightship, moored between Cape Melville and Pipon Island, was nowhere to be seen after the storm passed and was believed to have sunk at her moorings with the loss of four lives. The bodies of Captain Gustaf Fuhrman and the mate Douglass Lee were later found near Cape Melville amongst debris from the lightship.

It is estimated that some 300 pearlers lost their lives that night in Queensland’s most deadly natural disaster. While a dozen Europeans perished, most of the casualties were men and women from Torres Strait, the South Pacific, Japan and Malaya. Most were buried where their bodies were found with simple timber markers noting their final resting place. It was thought that as many as 100 local Aborigines were also killed during the storm and its massive tidal surge.

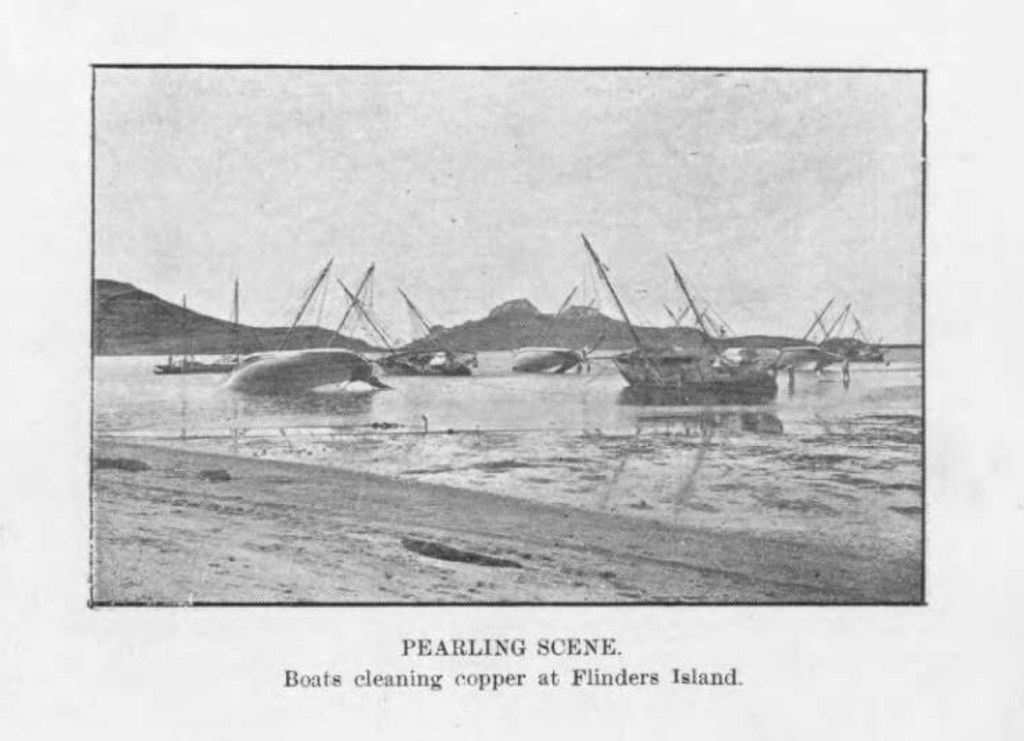

On Flinders Island, several dolphins were found washed up on rocks almost five metres above the high tide mark. One witness painted a vivid picture of the destruction at Bathurst Bay. “There is quite a forest of mastheads and floating wreckage, the boats having evidently sunk at the anchorage. There are tons of dead fish, fowl, and reptiles of all descriptions, and the place presents the appearance of a large cemetery. All the trees have been stripped of their leaves.”

Four schooners and 54 luggers were wrecked beyond repair, which devastated Thursday Island’s pearling industry. The human cost was even higher. With so many casualties, barely a family on Thursday Island escaped losing a loved one.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.