When, in 1866, the Board of Inquiry into the Loss of the Steam Ship Cawarra handed down its report, it was met with much incredulity. After poring over the evidence for six weeks, the commissioners could only conclude that the catastrophe was simply the result of bad luck. That was despite evidence presented to them that the steamer had been grossly overloaded when she had left port.

The SS Cawarra was a 439-ton side paddle steamer owned and operated by the Australian Steam Navigation Company, and regularly made the passage between Sydney and Brisbane. On what would be her last voyage, she had a crew of 36 and 25 passengers. In all, there were 61 souls on board. Around 6 p.m. on Wednesday, 11 July 1866, she passed through Sydney Heads on her way to Rockhampton via Brisbane. The northern settlement of Rockhampton had not been visited for some time, and basic provisions had run low. So, when the Cawarra’s hold was packed to capacity and no more would fit below, the remaining cargo was stowed on deck.

As soon as the steamer was heading north through open seas, she was assisted on her way by a strong south-easterly breeze. But during that first night, the weather steadily worsened. By morning, the winds were shrieking at gale force, the seas were mountainous, and the ship was being lashed by torrential rain. In the face of such foul weather, Captain Henry Chatfield decided to take shelter at Newcastle until it was safe to resume his journey.

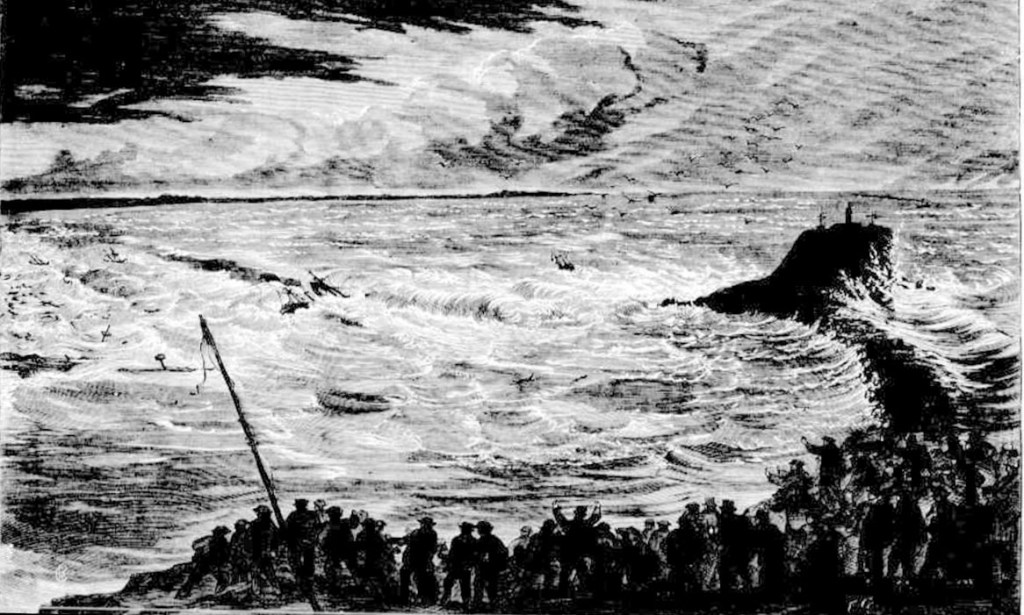

Chatfield sighted the distinctive outline of Nobby Head at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, and shortly after that, the steamer rounded the headland to enter the port. However, as the Cawarra was approaching the mouth of the Hunter River, she was struck by a series of large waves that swept over her deck and pushed her around so she was now facing back out towards Nobby Head.

It is thought that when Captain Chatfield realised his ship was in grave peril, he ordered the foresail to be set and tried to steam back out to sea. However, before he could do so, the Cawarra was hit by several more huge waves. They would spell her end. Water poured through the hatchways snuffing out the steamers’ fires. Now she was dead in the water at the mercy of the large seas. The ship then began to sink by the bow. Chatfield ordered the lifeboats to be made ready, but the treacherous seas swirling around the steamer made abandoning the ship impossible.

Around 3 o’clock, the Cawarra was driven onto Oyster Bank. The foredeck soon disappeared below the waves, and everyone had gathered on the poop deck or had climbed into the rigging to escape the rising water. Fifteen minutes later, the mainmast and funnel toppled into the sea, taking with them all those sheltering on the poop. The foremast went a few minutes later, tossing the remaining three or four men into the water, and the Cawarra quickly sank from sight. It was as if she had never been there to observers watching the horror unfold from Nobby Head. Only a few pieces of wreckage and cargo washed ashore to testify that a ship had been lost.

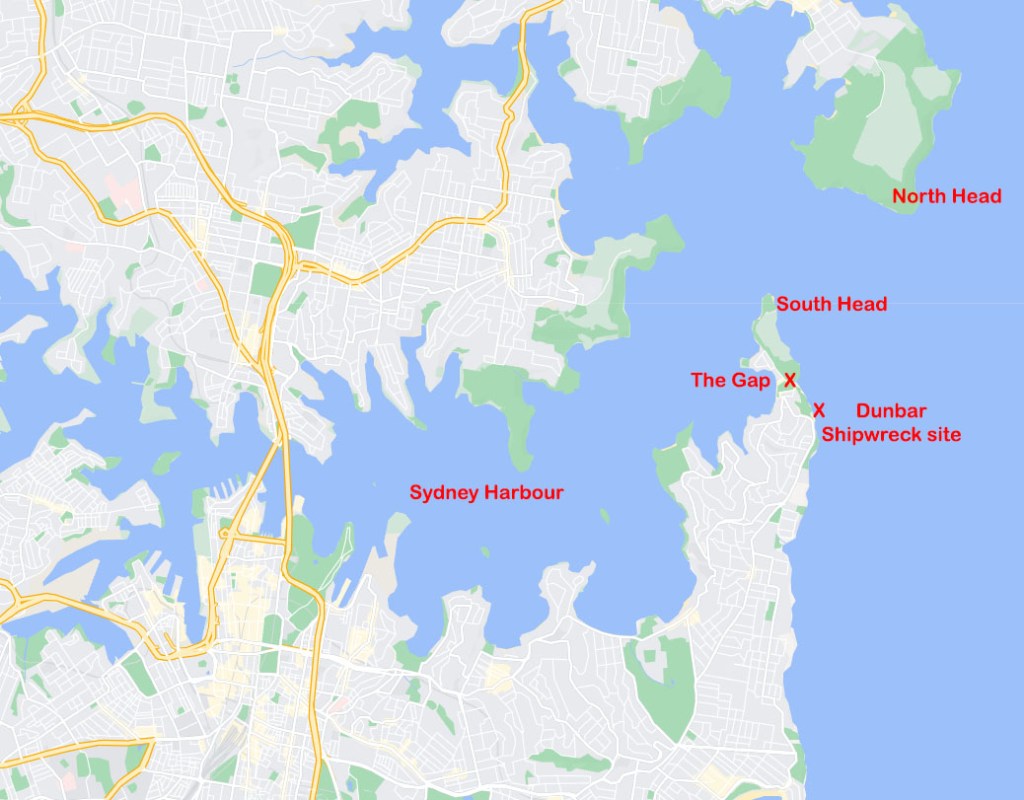

Sixty people died, while one man somehow managed to survive. Frederick Valliant Hedges had only joined the Cawarra eight months earlier. As the steamer began sinking by the bow, he had climbed high into the mainmast rigging only to be flung into the sea when the mast came crashing down. Hedges was later found clinging to a red buoy by a boat sent out from the lighthouse. Ironically, one of the rescuers was a man named John Johnson, who had himself been the sole survivor of the Dunbar when it sank off Sydney nine years earlier.

The violent storm wreaked havoc on shipping up and down the coast between Sydney and Port Stephens. Four more vessels foundered or were driven ashore at Newcastle, and another was wrecked near Port Stephens, further north. Several more were lost around Sydney. In all, 15 vessels were wrecked or driven ashore, adding another 17 fatalities to the grim final tally.

It is perhaps easy to blame the weather for the Cawarra’s loss. In fact, the commission established to investigate the circumstances found just that. Its report concluded: “We are of the opinion that the catastrophe was one of those lamentable occurrences which befall at times the best ships and the most experienced commanders, and which human efforts are powerless to avert.”

However, that explanation did not sit well with many folk. It had the whiff of a cover-up. Accusations that the Cawarra had been overladen when she left Sydney flew around maritime circles. She was reportedly carrying 450 tons of coal and cargo, which was 50 tons more than recommended by the ship’s builders. An engineer and surveyor from the Steam Navigation Board testified at the inquiry that when he had seen the Cawarra shortly before her departure, he thought she was sitting lower in the water than usual and believed she had been overloaded. But when he had raised his concerns with his superior and the ship’s owners, they both dismissed his concerns, telling him the Cawarra was a strong ship. The possibility that overloading could have contributed to the loss was even raised in the New South Wales parliament. The outspoken former clergyman and politician, Dr J.D. Lang, called for the Commission’s findings to be rejected, pointing out the contradictory evidence presented at the inquest. But it was all to no avail. The findings stood, and the loss was attributed to bad luck.

However, there were calls for a line to be marked on the hull of cargo ships to show when they were fully loaded. It would take another ten years before British parliamentarian Samuel Plimsoll was able to persuade his colleagues to take action. He was appalled by the number of ships and lives lost due to overloading. In 1876, the British Parliament passed legislation requiring markings on the sides of cargo ships, which would be submerged below the surface if the vessel was overloaded. This became known as the Plimsoll Line and is still in use today.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2023.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.