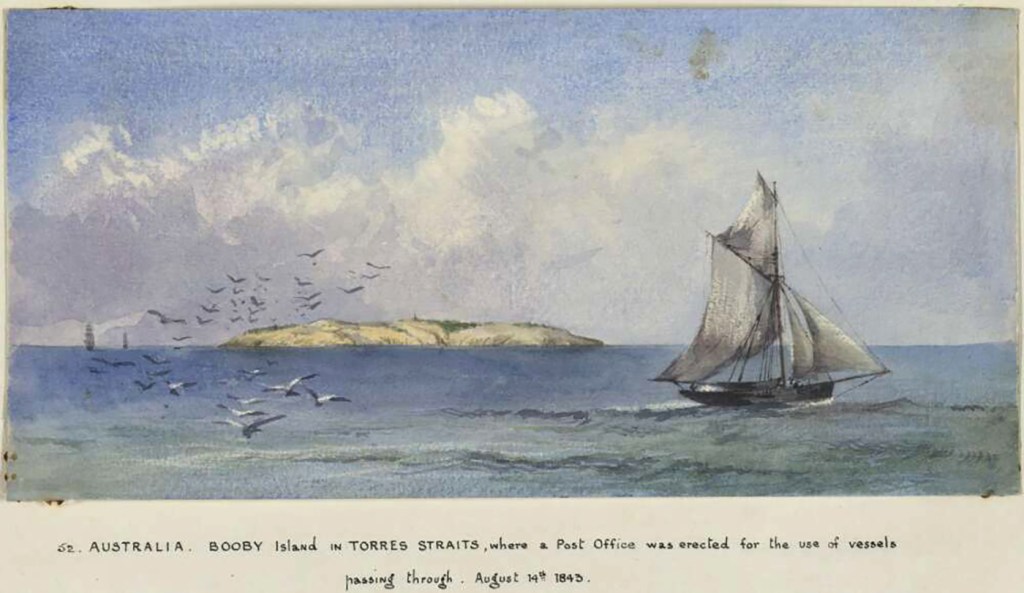

It might seem strange that one of Australia’s earliest post offices was also one of its most remote. It was set up on Booby Island in Torres Strait in 1835. However, the practice of passing mariners leaving correspondence on the island was already well established.

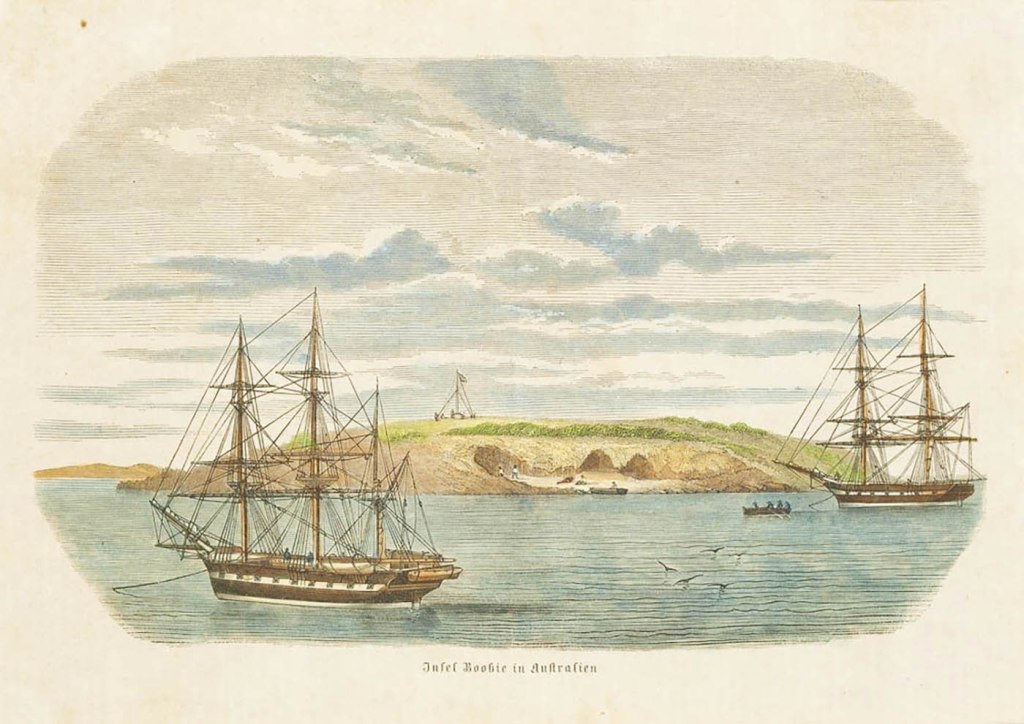

Booby Island (Ngiangu to the Torres Strait Islanders) lies west of the tip of Cape York, about 1,800 nm or 3200 km by sea from Sydney. The nearest European settlement was the Dutch outpost of Kupang on Timor Island, 2000 km west across the Arafura Sea.

Cook named the small outcrop Booby Island after the birds he saw nesting on its rocky slopes. The island would go on to serve as a crucial navigation landmark, especially for those mariners who had sailed up Australia’s east coast and were bound for Timor and beyond. Reaching Booby Island meant they had made it safely through the labyrinth of dangerous coral shoals plaguing the Torres Strait.

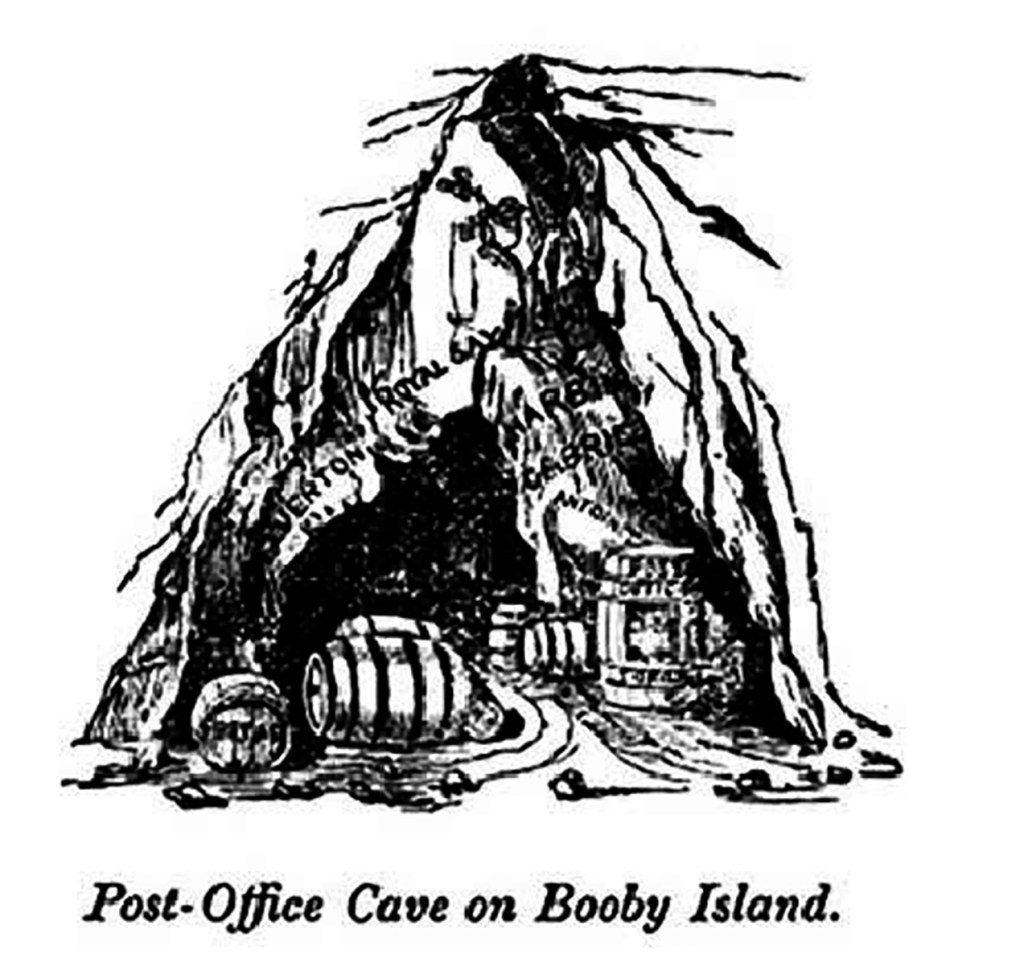

The earliest record of shipwrecked sailors finding refuge on Booby Island dates to 1814. The merchant vessel Morning Star, sailing from Sydney to Batavia, struck a reef and sank in Torres Strait. The crew abandoned the ship and made for nearby Booby Island. They were stranded there for five months, living in one of the island’s caves and surviving on rainwater and the seabirds that resided there. Then a sharp-eyed observer on a passing ship noticed a white flag being vigorously waved by one of the survivors. Five men were rescued. Twenty-two of their shipmates, including the captain, lost their lives.

By the 1820s, ships were regularly passing through Torres Strait on their way from Sydney and Hobart bound for ports in India, China and England. Too many ran aground or sank in those remote and treacherous waters.

In 1822, a flagstaff was erected on Booby Island’s summit, and a logbook was placed in one of the island’s caves so ships’ captains could register their safe passage through the Great Barrier Reef and Torres Strait. Those same mariners also began leaving sailing reports in the ledger to aid their fellow seafarers. The location of uncharted reefs or the strength and direction of hazardous currents were all recorded, sometimes at the cost of the vessel. Much of this information would be used to update later naval charts of the region.

Shortly after taking up duties as the Governor of New South Wales in 1824, William Bligh had the island stocked with barrels of fresh water, preserved meat and sea biscuits. Bligh knew stocking the island with provisions would go a long way towards saving the lives of sailors unfortunate enough to come to grief in those remote northern waters. He had first-hand knowledge of just how dangerous they could be. As a young Lieutenant, Bligh had sailed a small open cutter through Torres Strait after he had been unceremoniously relieved of his ship, HMS Bounty, by its mutinous crew.

Then, 11 years later, in 1835, Captain Hobson of HMS Rattlesnake established the unmanned “post office” in one of the island’s small caves. The practice of leaving details of sailing hazards continued. But mariners also began leaving letters in the box in the hope they might be taken on to various destinations by other passing ships. For example, someone on a ship bound for India might leave a letter addressed to a recipient in Canton, China. The next ship bound for that port would take it on to its destination.

When the Upton Castle stopped briefly at Booby Island in 1838, one of its passengers visited the post box and described it thus,“[it is] covered with canvas and well secured, and supplied with a quantity of pens, paper, and ink, and pencils in excellent order.”

It is worth remembering that the only other post office in Australia at the time was in Sydney. Melbourne would not get a post office for another couple of years and it would be seven years before another post office appeared in what would become Queensland.

In the span of just 15 years castaways from at least ten ships owed their lives to Booby Island. The Coringa Packet, and Hydrabad (1845) Ceres (1849), Victoria (1853), Elizabeth, Frances Walk It is worth noting that, at the time, the only other post offices in Australia were located in Sydney and Hobart. Melbourne would not get a post office for another couple of years, and it would be seven years before Brisbane got one.

In the span of just 15 years, castaways from at least ten ships owed their lives to supplies left at Booby Island. Survivors from the Coringa Packet, and Hydrabad (1845), Ceres (1849), Victoria (1853), Elizabeth, Frances Walker and Sultana (1854), Chesterholme (1858), Equateur, and Sapphire (1859) and many more before and since made for the island after their ships were lost.

Booby Island remained a vital refuge for shipwrecked mariners and a place to exchange information until the 1870s, when a government outpost was established on nearby Thursday Island.er and Sultana (1854), Chesterholme (1858), Equateur, and Sapphire (1859) and many more before and since made for the island after their ships were lost.

Booby Island remained an important refuge for shipwrecked mariners and a place to exchange information until the 1870s when it was supplanted by a government outpost on Thursday Island.

Copyright © C.J. Ison, Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2021.

To be notified of future blog posts, please enter your email address below.