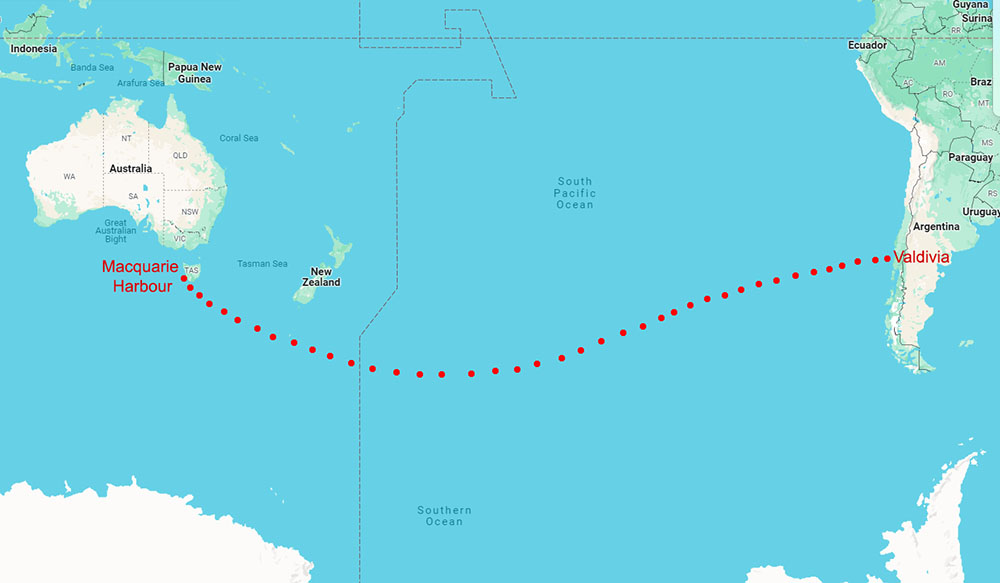

Edward Luttrell could not have imagined the ordeal he was about to face as he sailed out of Macao Harbour on his return to Sydney, NSW, in November 1805. What followed was a five-month ordeal that started with a shipwreck and included murder, piracy and starvation in one of the world’s most dangerous waterways.

Luttrell was the son of Edward Luttrell Snr, the assistant colonial surgeon for Sydney and Parramatta. He was also the first mate of the 75-ton schooner Betsey under the command of Captain William Brooks.

The Betsey departed Macau on 10 November, with a crew of 13, including the captain, Luttrell, and a crew comprising a mix of Portuguese, Filipino and Chinese mariners. But in the dead of night, just 11 days into her voyage, the Betsey struck a reef south of the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea.

Captain Brooks immediately sent some of the crew out in the jolly boat to set an anchor aft, hoping he could kedge the schooner back off the reef. However, the schooner would not budge, and eventually the cable snapped under the strain of trying. Huge swells surged over the stricken ship through the night pushing it further onto the reef. Once there was sufficient light to see their surroundings, Captain Brooks found that they were now stranded in two feet of water on a massive coral shelf that extended for miles in every direction.

Captain Brooks and his men tried everything they could to get the schooner off the reef, but to no avail. After four gruelling days, the crew had been worked to exhaustion, and Brooks had no choice but to give up any hope of getting the schooner into deep water. On 24 November, they abandoned the Betsey in the jolly boat and a makeshift raft. Brooks intended to make for Balambangan Island, about 200 km to the southeast. But from the outset, they were hampered by a “brisk gale” blowing from the northwest. On that first day, the raft, with eight of the men, became separated from Brooks, Luttrell and the remaining three sailors in the jolly boat. They were never heard of again.

For the next four days, it continued to blow hard, but as the sun rose on 29 November, land was sighted, which Brooks is reported to have supposed was “Balabae,” which might have been the northernmost point of Borneo south of their intended destination. By then, their supply of fresh water had been consumed, and they had been reduced to drinking their own urine to quench their burning thirst.

The jolly boat was then becalmed before they could make landfall, and they spent the day under the burning sun. That night, the wind came up again, and they were driven southeast again until they finally made landfall the next morning. Their first priority on landing was to find fresh water. They soon found a stream and drank their fill, and then, while they were stumbling around in the forest looking for something to eat, they were met by a pair of Dayaks. The Dayaks gave them some fruit in exchange for a silver spoon, and the two parties each went their own way. Brooks, Luttrell and the rest of the castaways set up camp on the beach next to their boat, and the next morning, they were visited by more Dayaks. This time, they traded more silverware for fresh produce.

According to Luttrell, the local men pointed at Balambangan visible in the distance and indicated that the British outpost there had been abandoned. They also promised to return the next day with more food to trade. Brooks, Luttrell and the others prepared the boat for departure early the next morning, intending to set off as soon as they had obtained more supplies. This was around 4 December.

True to their word, the Dyaks returned, only this time there were nearly a dozen of them. It seems that when the visitors arrived, the jolly boat was already in the water, under the control of two seamen, while Brooks, Luttrell and the third Portuguese sailor were still waiting on the beach.

We have only Luttrell’s account of what happened next, but he later claimed they had been conversing with the Dayaks, and all seemed well when they were attacked without warning. Captain Brooks was speared through the torso, while Luttrell and the Portuguese sailor were set upon. Luttrell parried off his attackers with his cutlass, giving him the precious few seconds he needed to wade out to the waiting boat. The sailor, covered in his own blood, also made it into the jolly boat, but Captain Brooks was not so lucky. He pulled the spear from his body and tried to make a run for it, but he was easily caught and hacked to death.

Luttrell and the others got clear of land, but the injured Portuguese sailor died of his wounds about 15 minutes later. This left just the mate and two seamen from the Betsey’s 13-man crew. When Luttrell tallied their provisions, he found they had 10 cobs of corn, three pumpkins, and two bottles of fresh water. That would have to last them until they reached the Malacca Strait, over 1500 km away.

They made steady progress on a southwesterly course under sail for the next ten days. While their food quickly ran out, they were fortunately kept well supplied with drinking water from frequent squalls that passed over them. However, by 14 December, they were starving and exhausted from the constant vigilance needed to avoid another attack in those dangerous waters.

On 15 December, they were passing through a small group of islands in the Malacca Strait around 3N 100W. If their intended destination was actually the European settlement at Malacca, they had overshot it by some 200 km. Otherwise, it is not clear where Luttrell intended to stop.

Anyway, it was here that three Malayan praus intercepted them. They tried to flee, but as soon as the praus came within range, they unleashed a volley of spears, killing one of the Portuguese sailors and wounding the other. Luttrell had a lucky escape when a spear passed through the brim of his hat, narrowly missing him. Unable to outrun the attackers and too weak to resist, Luttrell surrendered. The pirates boarded the jolly boat and stripped it of everything of value. A few remaining pieces of silver plate taken off the Betsey, the ship’s logbook, the sextant and even the clothes they had been wearing were all taken. Luttrell could not have held out much hope that he would survive much longer. But survive he did.

He and the wounded Portuguese sailor spent three days on one of the praus, exposed to the blistering tropical sun and kept alive on a meagre diet of sago. They were then landed at an island, Luttrell named Sube, but which today offers no real clue to where they had been taken. Luttrell wrote that they remained there “in a state of slavery, entirely naked, and subsisting on sago,” for nearly four months.

Then, in late April 1806, they were put aboard a prau and taken away. After 25 days at sea, they landed in the Riau Islands. Luttrell and his companion were nearly starved to death. But their fortunes were finally about to change for the better. Luttrell wrote that a Mr Kock of Malacca took them in. The circumstances of their coming under his protection are not recorded. However, when Mr Kock returned to Malacca on the Kaudree, Luttrell and the Portuguese sailor were with him. Luttrell seemed to recover from his ordeal and, in time, returned to Sydney.

The incident was first reported in the Prince of Wales Island Gazette, and later republished in the Sydney Gazette on 1 March 1807.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2025.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.