By December 1833, the penal settlement at Macquarie Harbour in southwest Tasmania was all but deserted. Only a dozen convicts remained to complete the 120-ton brig Frederick. She would be the last of nearly 100 vessels to be built there. Once launched, they were supposed to sail her around to the newly established station at Port Arthur. However, ten of the convicts had a much more distant destination in mind.

But, to seize the ship involved overpowering the soldiers and officers left behind to watch over them. Tackling armed men with just bare hands was daunting, but they had a plan. One of the convicts, John Barker, happened to be a master blacksmith. He manufactured two flintlock pistols using discarded scraps of metal and a musket barrel found in the blacksmith shop. He also forged a pair of tomahawks to add to their small arsenal.

The Frederick was finished on 10 January 1834, and at 10 am the next day they set sail. Captain Taw sailed down the length of Macquarie Harbour but dropped anchor inside the heads. He judged the weather too foul to safely pass through the narrow passage of Hells Gate and out to sea. So they waited. Then, on Monday, 13 January, the wind eased, signalling their imminent departure.

For the ten convicts, the time to strike had arrived. If they did not seize the ship now, they likely never would. However, they were up against nine men, seven of whom were armed.

Then, good fortune smiled upon them, and the odds shifted in their favour. Two of the soldiers went fishing and took a boat out with a convict at the oars. He was one of two prisoners not in on the plan. So, with them gone, nine had been reduced to six.

Around 6 o’clock in the evening, a prisoner beckoned a sentry to join him by the forecastle hatchway. When the unsuspecting soldier obliged, he was jabbed in the chest with one of Barker’s pistols and ordered down the ladder into the crew’s cabin. Meanwhile, two other convicts armed with hatchets pounce on the only other two men on deck. They subdued the remaining soldier and the terrified mate, bundling them too into the forecastle cabin. A convict stood guard, and a heavy kedge anchor was dragged across the hatchway cover in case they tried to escape. The convicts now had control of the deck. Three men were confined in the forecastle, and another three were out fishing, oblivious to what was unfolding on the Frederick. This just left Captain Taw, David Hoy the shipyard supervisor, and the convict steward William Nicholls. All were in the captain’s cabin

The convicts, now armed with the soldiers’ muskets, were ready to confront the last men standing between them and liberty. Three men stormed down the ladder and attacked Captain Taw and the others, hoping to quickly get the best of them. However, Taw and Hoy fought back. Hoy wrestled a pistol from one of the convicts, and the attackers retreated back up the ladder, leaving Taw, Hoy and Nicholls trapped in the cabin, bloodied and bruised from the brief but violent encounter.

Taw and Hoy were trapped in the cabin. The convicts would pay dearly if they attacked again, but the captain knew he could not retake the ship. They were at a stalemate. But Captain Taw had one small bargaining chip. He had possession of the Frederick’s navigation instruments, items the convicts would need to escape. The impasse lasted about ninety minutes, with occasional shots fired through the cabin’s skylight and each side calling for the other to surrender.

Around 7.30 in the evening, someone called for the pitch pot to be brought over and threatened to empty its boiling contents into the cabin if the trio did not immediately surrender. Hoy and Taw agreed there was nothing to be gained by holding out any longer and gave themselves up.

Meanwhile, the fishing party had returned to the brig after hearing gunfire, only to find the prisoners already in charge. The rest of Frederick’s men joined them in the boat, and they were sent ashore with half the ship’s provisions.

Taw and Hoy assessed their situation. There was plenty of food, so they would not be going hungry any time soon. However, how long would it be before a ship was sent to investigate the whereabouts of the Frederick? Taw had no intention of waiting to find out. They set off on foot for the nearest settlement, 150 kilometres away. It would take Taw over two weeks to eventually reach Hobart to report the incident.

In those two weeks, the mutineers did not waste any time making good their escape. James Porter, one of the convicts, wrote the only record of what happened to the Frederick next.

Porter was not a typical convict transported to Australia. For a start, he was born into a respectable middle-class family. When he was 12, he dropped out of school and, by his own account, began mixing with the wrong kind of people. Porter soon got himself in trouble with the law, but his father pulled some strings, and the charges were dropped. However, to prevent Porter from getting into any more trouble, he was sent to sea to serve an apprenticeship and found himself bound for Rio de Janeiro.

So began his career as a seaman. After changing ships several times, Porter claimed he had spent 12 months on the armed schooner Liberta helping the Chileans win their independence from Spanish rule. However, by late 1821, he had had enough of life in South America and returned to England.

A year later, Porter was caught breaking into a house and was transported to Van Diemen’s Land for life. He landed in Hobart in January 1824 but was soon caught stealing and sent to Macquarie Harbour.

When he was chosen to remain behind to finish work on the Frederick, a plan started to take shape in his mind, and South America once again beckoned. His companions comprised a mix of experienced seamen like himself, shipwrights and the blacksmith John Barker who had been schooled in celestial navigation, though he proved to be no seafarer.

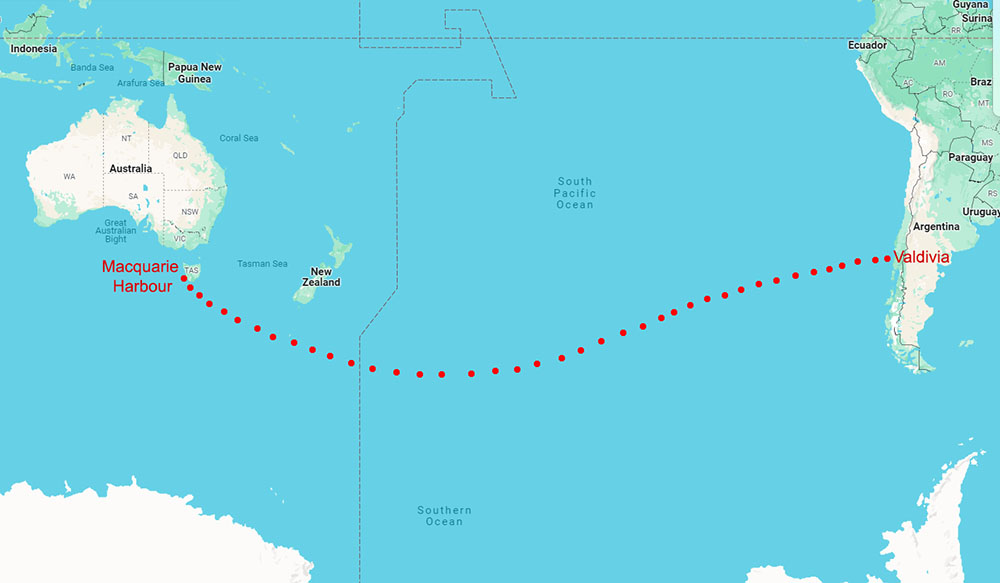

The Frederick no sooner made it out to sea when the wind freshened to a heavy gale. It blew hard with mountainous seas for the next nine days as they bore south, then east under much-reduced canvas. The burden of sailing fell heavily on the shoulders of the seasoned sailors. The rest of the men, unused to such sea conditions, rarely left their bunks, suffering severely from sea sickness. Barker was particularly prone to the malady, only coming on deck periodically to make observations and plot their course.

After being at sea for about three weeks with few opportunities to take observations, Barker found they had strayed too far south into the dangerous icy waters of the “Furious Fifties”. He set a northeasterly course for the helmsmen and then retired to his quarters again. Shortly after this, their voyage nearly came to an end when the Frederick was heeled over on her side by a powerful wind gust.

Fortunately, the ship righted herself once the canvas had been brought in. Then, about six weeks out, they spotted land for the first time since leaving Tasmania. They had sailed nearly 5,400 nautical miles (10,000 km) and arrived off the coast of South America.

On 27 February, they boarded the longboat and left the Frederick to sink as, by now, she was taking on a lot of water. The next morning, they made landfall near the mouth of the Rio Bueno in Chile. A week later, they arrived at the provincial capital of Valdivia, where they were promptly thrown in gaol for entering the country in a “clandestine manner.”

It was obvious to the Chilean officials that the men claiming to be shipwrecked sailors were not what they claimed to be. Now that they were behind bars and facing an uncertain future, Porter and his comrades decided to admit to being runaway convicts and beg the Governor for asylum.

They found a sympathetic ear in Governor Sanchez, and he agreed to petition the President of Chile in Santiago on their behalf. They were released from gaol after promising not to leave town. All ten men found work at the local shipbuilding yard, where their skills were much in demand. As time passed, they settled into their new lives and felt their troubles had been put behind them.

But the British Consul in Santiago had learned of their presence in Valdivia unbeknownst to Porter and his colleagues. He, in turn, had called on the Royal Navy to dispatch a ship to apprehend the runaways.

Eight months later, in February 1835, HMS Blonde dropped anchor at the mouth of the Valdivia River to collect the runaway convicts. However, Governor Sanchez refused to hand them over, and the British warship left empty-handed. While Porter and the others had avoided arrest this time, it was clear to them that the British knew where they were.

Life settled back into its regular routines until a few months later, when Governor Sanchez was replaced by a man far less sympathetic to the runaway convicts. Within a month, three of the convicts departed on a merchant ship bound for North America. Then Barker and two others left in the dead of night in a whaleboat they had been building for the new governor. The governor was furious and gaoled Porter and the other three until they could be handed over to the Royal Navy.

They were put on board the next British warship that stopped at Valdivia and returned to England. As they had escaped from Van Diemen’s Land, it was decided to return them there to stand trial for piracy. They arrived back in Hobart on 29 Mar 1837 after an absence of more than three years.

In a novel legal argument, Porter contended that because the Frederick had never been officially registered, it could not be considered a ship. Instead, it was just a collection of timber, ropes, canvas and such like, which just happened to resemble a brig. Consequently, he argued, they could not be found guilty of piracy. The jury was unconvinced, and after 30 minutes of deliberation, they returned a guilty verdict, and the four men were banished to Norfolk Island for life.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2025.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.