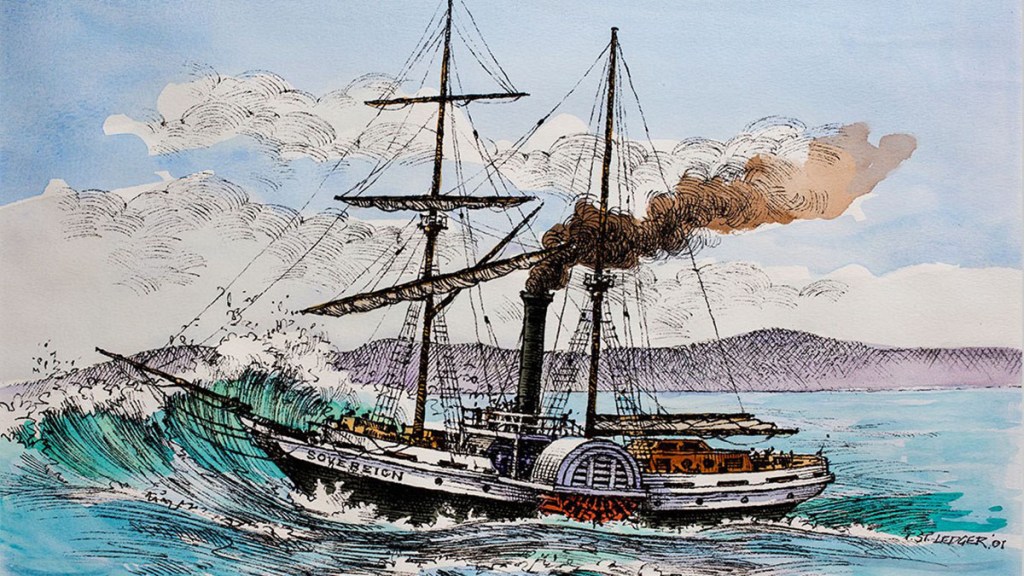

TEN: SOVEREIGN, 1847.

The paddle steamer Sovereign, with 54 persons on board, sailed from Moreton Bay via the southern channel on 11 March 1847. As she ploughed through the large swells funnelled into the passage between Moreton and Stradbroke Islands, her engines failed at a critical moment. The force of the breaking waves quickly drove her onto a sand spit projecting from the southern point of Moreton Island, where she broke up. Forty-four people lost their lives. The owners of the vessel would later claim the engines had been working fine and blamed the captain for the loss.

NINE: MERSEY, 1804.

On 24 May 1804, the 350-ton merchant ship Mersey sailed from Sydney bound for Bengal, India, via Torres Strait. In mid-June she was wrecked while trying to negotiate the dangerous waters of Torres Strait. Neither the location or the circumstances of the tragedy are known, other than the captain and either 12 or 17 of the crew took to the longboat and made it safely to Timor Island to report the loss. She reportedly sailed with 73 hands which means 56 or 61 people lost their lives.

EIGHT: PERI, 1871.

In early February 1871 HMS Basilisk discovered a schooner, later identified as the Peri, adrift and seemingly abandoned a short distance off the Queensland near Cardwell. When a boat was sent across to investigate, they discovered 14 emaciated Solomon Islanders, three corpses, no food or fresh water and five feet of putrid seawater in the hold. The Peri had last been seen about six weeks earlier in Fiji carrying around 80 or 90 blackbirded Islanders bound for Fijian cotton plantations. It seems that the Islanders had overpowered their kidnappers and taken control of the schooner. They then sailed or drifted west across almost 3,000 km of open ocean, withstood at least one severe tropical storm, and passed through a gap in the Great Barrier Reef before being found. As many as 75 people likely died during the ordeal.

SEVEN: SYBIL, 1902.

The labour schooner Sybil disappeared sometime after leaving the Solomon Islands on 19 April 1902 bound for Townsville with a fresh batch of South Seas labourers. By August, grave fears were held for the Sybil, for the voyage should not have taken more than two or three weeks. Searches were made of the islands along the outer Great Barrier Reef and in the Coral Sea but no trace of the vessel or any of those on board were found. She had a crew of 12 and on the previous two voyages, she had carried 90 and 98 labour recruits, so it is thought no less than 100 lives were lost.

SIX: GOTHENBURG, 1875

The steamer Gothenburg sailed from Darwin on 17 February 1875 bound for Adelaide via Australia’s east coast. On 24 February the Gothenburg was steaming down the coast in the vicinity of Cape Bowling Green. Bad weather meant they could not see the regular landmarks to aid their navigation. The captain was unaware strong currents were pushing the ship towards the Great Barrier Reef until it was too late. The Gothenburg ran aground on Old Reef. The ship and all aboard her would likely have been saved but for a powerful cyclone bearing down on them. As the storm worsened, the captain ordered the evacuation of the passengers, but as the women and children were being loaded into the lifeboats a succession of huge waves swept over the ship. Only 22 people survived. As many as 112 passengers and crew lost their lives.

FIVE: YONGALA, 1911

The Yongala sank during a tropical cyclone near Cape Bowling Green on 11 March 1911 with the loss of all 122 people on board. When the ship failed to arrive in Townsville as scheduled, concerns were raised. Then, wreckage began washing ashore along the coast as far away as Hinchinbrook Island. However, there was no sign of the ship or any hint as to where she might have sunk. Nearly half a century would pass before the final resting place of the Yongala was conclusively located.

FOUR: QUETTA, 1890

While the Mail Steamer Quetta was steaming through Torres Strait on the night of 28 February 1890, it struck an uncharted rock pinnacle as it passed Adolphus Island. The Quetta had departed from Brisbane bound for London carrying nearly 300 people comprising the passengers and crew when disaster struck. The collision tore a gaping hole in the hull from bow to amidship, and the ship sank in just three minutes. One hundred people made it safely to Little Adolphus Island where they were later rescued. Dozens more were pulled from the water the following day. 133 people lost their lives in the tragedy.

THREE: AHS CENTAUR, 1943

At 4 am on 14 May 1943, the Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Centaur was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine. The Centaur was about 35km off Moreton Island having departed Sydney with medical staff from the Army’s 2/12 Field Ambulance bound for Port Moresby. In all, there were 332 people on board. 268 lost their lives. 64 survived by clinging to debris and two damaged lifeboats until they were rescued 36 hours later.

TWO: CYCLONE MAHINA, 1899

On the night of 4/5 March 1899, a powerful cyclone crossed the coast at Bathurst Bay on Cape York Peninsula. Lying directly in its path was the North Queensland pearling fleet which had sought shelter there. Nearly 60 vessels – from large schooners to pearling luggers – were sunk or driven ashore with horrendous loss of life. Between 300-400 people died in what is no doubt Queensland’s worst natural disaster. The loss was most keenly felt on Thursday Island where the pearling fleet was based.

ONE: GRIMENEZA, 1854

The worst shipwreck off the Queensland coast occurred on 3 July 1854. The Peruvian ship Grimeneza was sailing from China with some 600 Chinese labourers bound for the Callao guano mines in Peru. When they struck a reef at Bampton Shoals in the Coral Sea, the captain and six others immediately abandoned the ship leaving the rest of the crew and the passengers to their fate. The rest of the crew tried to back the ship off, but when that failed, they too took to the lifeboats and were picked up 12 days later. Miraculously, the Grimeneza floated off with the next high tide. The labourers sailed the damaged ship west towards the Queensland coast with the pumps being worked around the clock. But after three days of exhausting work, she foundered. Six men were found clinging to a piece of wreckage 300 km off the coast a few days later. The rest had all drowned or been taken by sharks.

© Copyright, C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

If you would like to be notified of future blog posts, please enter your email address below.