The loss of some ships plying Australian waters was only ever noted by a brief paragraph in newspaper shipping columns. Months after leaving port, they would be reported as having never arrived at their destination. The exact circumstances of their loss and what might have happened to the souls on board will never be known. But far more often, people did survive, even if the ship did not. Captains had the grim duty to report the loss of the vessel to its owners, while passengers often wrote to loved ones about their unanticipated adventure. Such records are the sources for many a shipwreck tale.

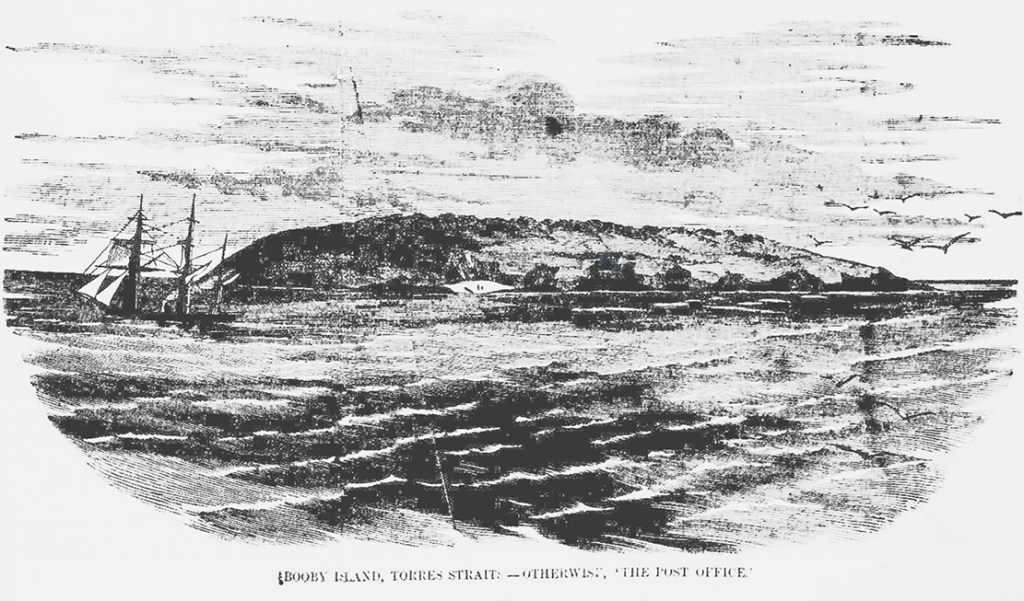

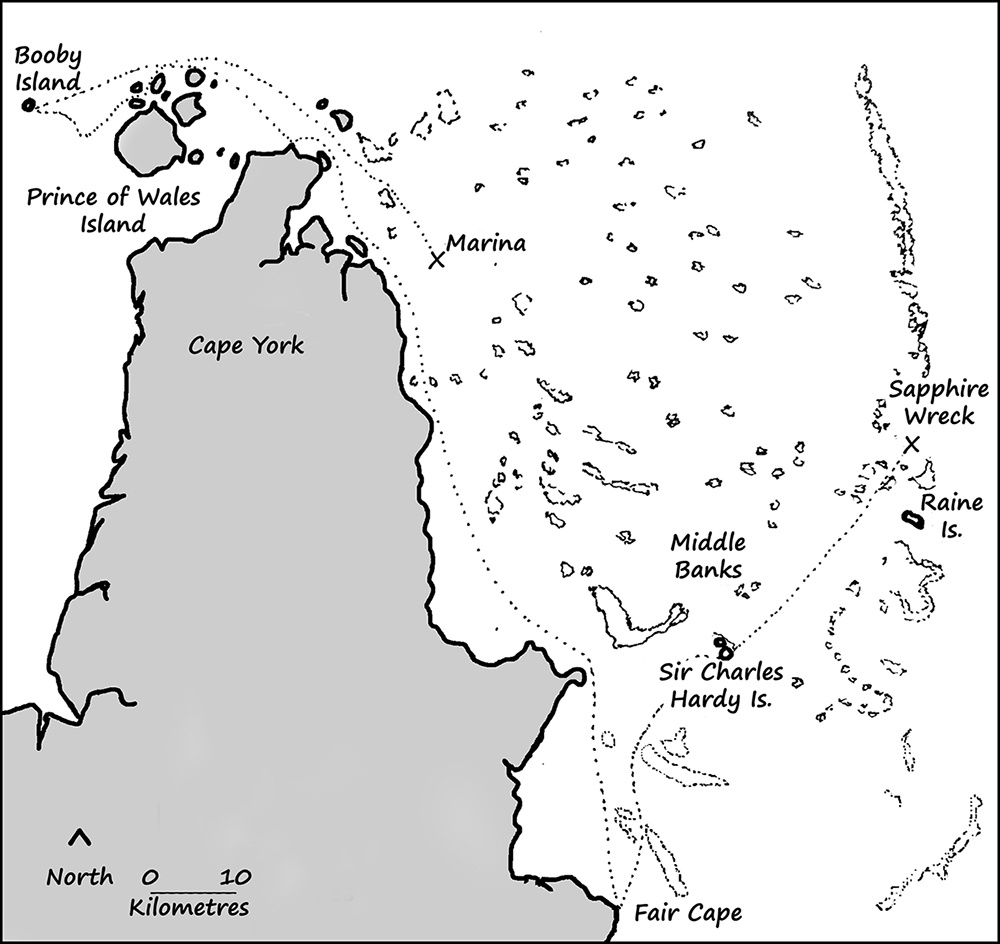

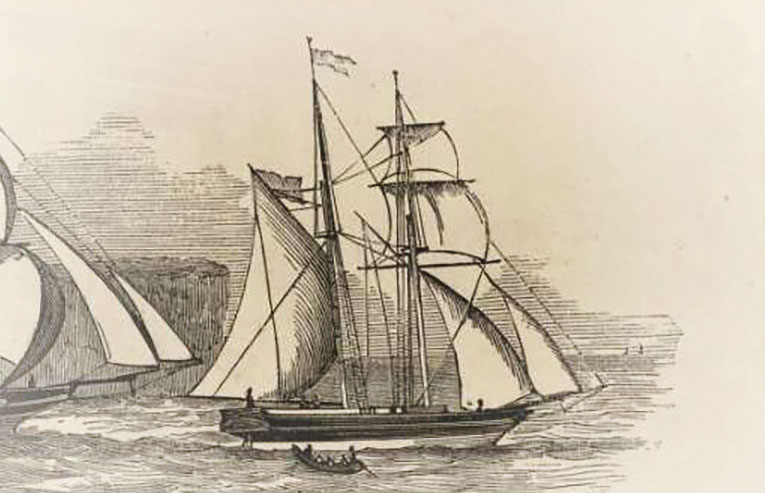

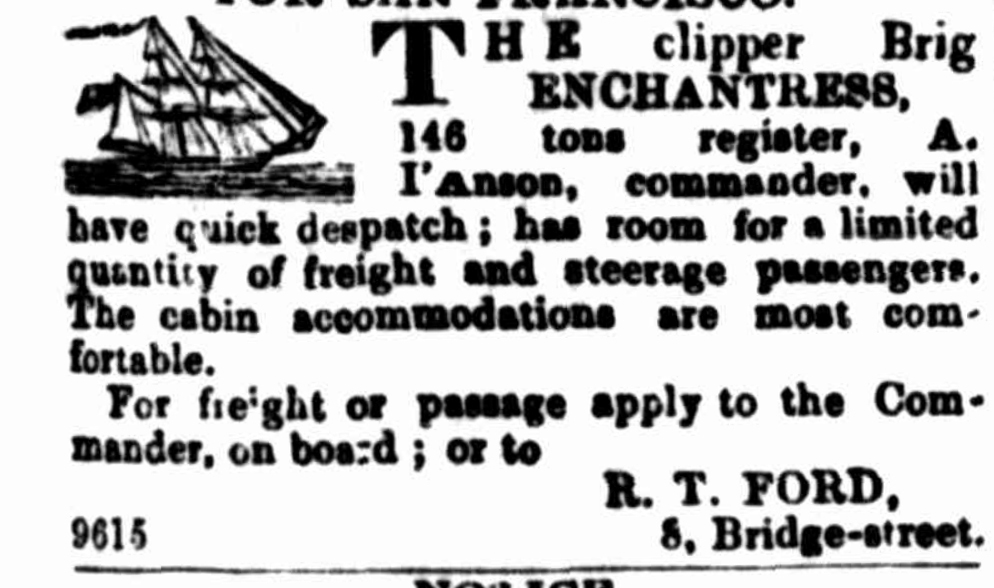

On 24 July 1850, the 146-ton brig Enchantress was wrecked near Raine Island while trying to pass through the Great Barrier Reef. Navigating the tricky passages leading to Torres Strait could prove challenging in those early days. Between 1791 and 1887, no less than 37 ships came to grief near Raine Island. Many more were lost on reefs and shoals dotting Queensland’s northern waters.

Mr B. Buchanan was a passenger on the Enchantress and also an employee of the company that owned the vessel. While en route to Kupang in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia), after being rescued, he penned a letter to his employers, notifying them of the loss of their ship. This letter, written 175 years ago, provides a firsthand account of the incident.

Messrs. Smith, Campbell, and Co., Sydney.

At Sea, approaching Kupang,

August 3rd, 1850.

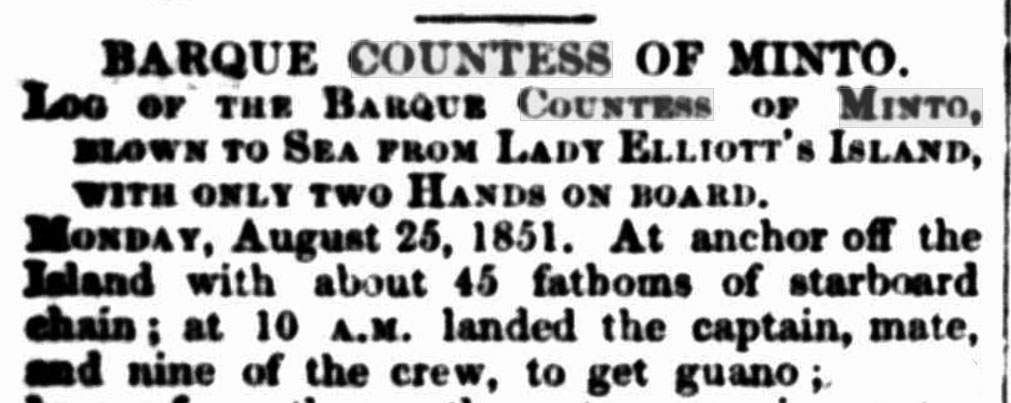

Dear Sirs, – It is my unpleasant task to inform you of the loss of the brig Enchantress. She struck and grounded on the reef running out from Raine’s Island, on the afternoon of the 24th July.

From the time of leaving Sydney, the weather was favourable. We joined company with the brig Lady Margaret off Newcastle. On the 24th, about noon, being a little ahead of our companion, we sighted the Barrier below the detached reef, between it and Yule’s Reef. We hauled up to the eastward, and made out the beacon on Raine’s Island between two and three pm.

Captain L’Anson then stood in for the southern passage, but unfortunately got too near the reef running out from the island. He tried to put her about, but she missed stays; he filled on her again, and again tried it, but a second time she missed. There was no room to wear, the wind being fresh and the current strong, and we tried a third time to stay her, but to no purpose. The strong northerly set and flood tide prevented her [from] coming round, and we were driven on the point of the reef.

Every sea sent us further on, the surf washing the lower masts’ heads. An attempt was made to take off the sails, but it was becoming dark, we had the reef to cross to get to the island, and the brig was thrown more over by every wave.

We therefore got out the longboat, saving the chronometer, my papers, and some clothes. The jolly boat was washed away. We crossed the reef without difficulty and took shelter in the beacon.

At three a.m. of Thursday, the 25th, Captain L’Anson, it being low tide, started with the boat, manned by the majority of the crew, with the intention of saving all he could from the wreck. He got the boat alongside, but the sea was breaking so heavily that it was not possible to remain; they brought away some provisions, cooking utensils, and nearly all my things, but could save nothing pertaining to the ship. They were afraid of the boat being swamped.

At the time of our first attempting to stay the brig, the Lady Margaret was following close, but immediately went about. Captain Grant stood off that night, bore down again in the morning, and worked on and off all day.

We knew that it would be out of all reason to expect him to bring up after having once entered, before he got to anchorage ground, about twenty-five miles from Raine’s Island; and saw also that he was unwilling to pass without communicating with us (we learnt afterwards that he was afraid we were without provisions or water).

Meanwhile, the weather had assumed a threatening aspect, we therefore dispatched the boat with five of the people, under Mr Wood, the chief officer, to the Lady Margaret; they succeeded in reaching her after a very long and laborious pull.

I had written to Captain Grant, with suggestions for relieving us, but his position was one of such danger that he could give no attention thereto; his anxiety was to get us on board at once, and be off, and to attain this he despatched his second officer with his jolly boat to the island immediately, our own boat returning at the same time to aid in bringing what clothes we had saved.

We left the island at four p.m., and were taken on board the Lady Margaret at dusk. She stood out to sea, and in the morning entered by the Southern Passage.

The poor Enchantress when last seen by us was being between twenty and thirty yards from the point of the reef – bows on the water, masts standing.

[The letter was published in the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper on 3 December 1850. Here, it is re-published as it first appeared in print, but for a few minor changes to spelling and punctuation.]

[The letter was first published in the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper on 3 December 1850. Here, it is reproduced as it appeared in the newspaper, but for a few minor changes to spelling and punctuation.]

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.