In the early hours of Friday, 2nd April 1852, a band of villains climbed aboard the barque Nelson while moored in Melbourne’s Hobsons Bay and made off with over 8,000 ounces of pure gold, worth tens of millions of dollars in today’s money. The heist was as simple as it was audacious and ranks among the largest robberies in Australian history. Most of the thieves never saw the inside of prison, and only a fraction of the gold was ever recovered.

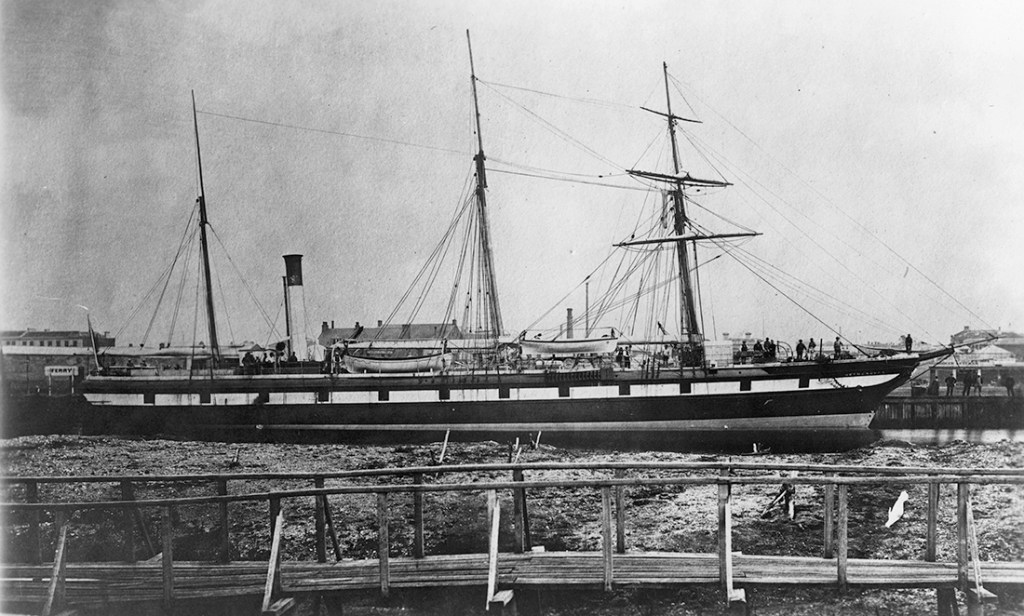

The 603-ton barque Nelson had sailed from London on 4 July 1851, around the same time that prospectors discovered a vast quantity of alluvial gold near Mount Alexander. The barque dropped anchor in Hobsons Bay on 11 October, only for its captain, Walter Wright, to learn Victoria was in the midst of a gold rush.

The Nelson disembarked its passengers and unloaded merchandise at Williamstown, then sailed across to nearby Geelong. There, the crew deserted the ship and headed off to the gold fields to try their luck, leaving just the captain and first mate behind. Over the next couple of months, the Nelson’s hold was filled with bales of wool, casks of tallow, and, most importantly to this story, 11 boxes of gold totalling 2083 ounces, all bound for London. By March 1852, the barque was once again anchored off Melbourne in Hobsons Bay, ready to return home as soon as enough men could be found to crew her.

On Thursday night, 1 April, the Nelson was still anchored a short distance off the Point Gellibrand Lighthouse, along with scores of other ships stranded for lack of crew. Captain Wright was ashore for the night, leaving his chief mate, Henry Draper, in charge. With him were the second mate Carr Dudley, an officer from a neighbouring ship, plus a handful of seamen they had managed to recruit.

Despite a fortune in gold being on board, no watch had been posted. The crew had refused Draper’s order to stand guard through the night, saying there were too few of them to do so, and besides, they had not signed on as night watchmen. All Draper could do was lock the boxes of gold in the lazarette, (a storeroom of sorts) for safekeeping. By now, the number of boxes had grown to over twenty as the captain continued to accept new consignments.

Henry Draper, Carr Dudley, and two officers from nearby ships spent the evening playing cards and drinking. Then, sometime around 11 p.m., the card game wrapped up, and one of the visiting officers returned to his ship. Draper and Dudley tottered off to their cabin, leaving William Davis, the Royal George’s second mate, to sleep off the evening’s entertainment on the cabin’s lounge. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew had long since retired to their berths in the forecastle.

Around two hours later, two boats carrying 22 men rowed up to the Nelson, the sound oftheir oars muffled by blankets to mask their approach. They pulled alongside, and a dozen of them, armed with pistols and swords, climbed onto the deck.

Some went forward and secured the crew in the forecastle while the rest poured into the main cabin aft. As they swarmed onto the deck, Carr Dudley woke Draper up to tell him he thought he could hear movement above. Draper went on deck to investigate and was confronted by several well-armed men, all dressed in black with hats pulled low over their heads and handkerchiefs covering the lower portions of their faces.

“We’ve come for the gold,” the ringleader told Draper, “And the gold we’ll bloody well have.” Draper had gone on deck dressed only in his nightshirt and asked if he could return to his cabin to put on a pair of trousers. While he was fumbling to get dressed, a robber, still pointing a pistol at him, warned, “We’ve not come here to be played with, so make haste. ”Draper and Dudley were forced into the main cabin to join Davis, who had been rudely awoken with a gun pointed at his head. They were eventually joined by the rest of the crew brought aft from the forecastle.

Draper was forced to unlock the lazarette, and the thieves helped themselves to 23 cedar boxes containing over 200 kilograms of gold. During the proceedings, one of the robbers’ pistols accidentally discharged, and the bullet grazed Draper’s thigh. Once the gold was loaded onto the boats, the slightly wounded Draper and the rest of the crew were locked in the lazarette. The robbers then hopped in their boats and were rowed back to shore.

Draper and the others would have remained imprisoned in the lazarette until well into the day had they not had a minor stroke of luck. The cook had been woken by the noise of the thieves climbing on deck, and he had hidden in a dark recess under his bunk, remaining undiscovered during the robbery. He resurfaced once he saw that the robbers had left and went aft to find his shipmates locked in the lazarette. Once released, Draper wasted no time reporting the heist to the Williamstown water police office.

Boats were sent out to scour Hobson’s Bay, but they were too late. The robbers had got away. Shortly after daylight, the water police found one of the whaleboats pulled up on the beach at Williamstown and the other across the bay near Sandridge (present day South Melbourne). Tracks were seen leading off the beach where the boat had been abandoned.

The police were galvanised into action. Mounted officers and constables fanned out across Melbourne looking for the robbers and the missing gold. The robbery was a severe embarrassment to the police and the colonial government, and both were widely condemned in the newspapers when it became public. The Governor offered a £250 reward, and that was matched pound for pound by the Nelson’s shipping agents.

The empty gold boxes were discovered by an employee of the Argus newspaper a few days later, hidden in scrubland not far from the beach at Sandridge, but most of the gold was long gone. Only some slight traces of gold dust could be seen mixed in the sand where the boxes had been busted open. Over the next several days, police rounded up anyone who looked remotely suspicious, and the watchhouses were filled to bursting.

The police finally got a lucky break when a band of men turned up at a hotel in Geelong late one night wanting a room. They were dressed far beyond their station in life and spent their money freely. The publican alerted the Geelong police, and they were arrested a couple of days later. These seven men were detained while the police searched for evidence of their involvement in the Nelson robbery. Two more men were captured in Portland on Victoria’s western coast. Most of the individual suspects were found to possess more than £500, five times the average yearly wage at the time.

Of these nine men, only three were found guilty of the robbery and sentenced to long terms in prison. The most compelling evidence against them was that they had been recognised by Henry Draper, or the Royal George’s second mate, William Davis. Drape and Davis claimed they recognised the robbers because their handkerchiefs had slipped down, revealing their faces. Draper and Davis also claimed they recognised two other men who likely had nothing to do with the robbery. One had a slew of witnesses testify at his trial that he had been on the gold fields at the time, but the jury did not believe them. However, he was quietly released a couple of months later when it was clear he and his witnesses had been telling the truth. The other hapless soul spent many years at hard labour for a crime he never committed.

For years, rumours circulated around Melbourne about who might have been involved. Ongoing interest was fuelled by the fact that most of the gold was never recovered. But it remained a baffling mystery.

Writing in the Sydney Morning Herald 30 years later, Marcus Clarke pondered some of the many rumours associated with the heist. It was often said that a gentleman of standing in Melbourne society had masterminded the robbery and paid thugs to steal the gold on his behalf. It was also rumoured that several prominent men about town had benefited financially from the robbery. Yet another rumour had it that a notorious publican had fenced the gold and then left the colony a very wealthy man. Clarke finally concluded that after the passing of so many years, the whole story would never be known.

But was he right? Since first writing this blog post in April 2024, I have unearthed some tantalising clues that point to the identity of the brazen thieves. But more about that some other time.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.