More than 160,000 of Britain’s most unwanted souls were banished to Australia between 1788 and 1868. These convicts ranged from petty thieves to hardened criminals. Fraudsters, burglars and pickpockets rubbed shoulders with highway robbers, rapists and murderers in the fetid prison cells of transport ships bound for Australia. Political prisoners, social reformers and ordinary men and women struggling to feed their families also found themselves trapped in a brutal judicial system determined to rid Britain of its undesirables.

The vast majority of these men and women made the best of the hand fate had dealt them. They earned their freedom and took up land and farmed it, started businesses, married, raised children, and helped found the country we know today. But this book is not about them. Library shelves are lined with volumes praising the accomplishments of those worthy and not-so-worthy folk. Rather, Bolters tells the stories of those unruly malcontents who stepped ashore and thought, “This place is not for me,” and began plotting their escape.

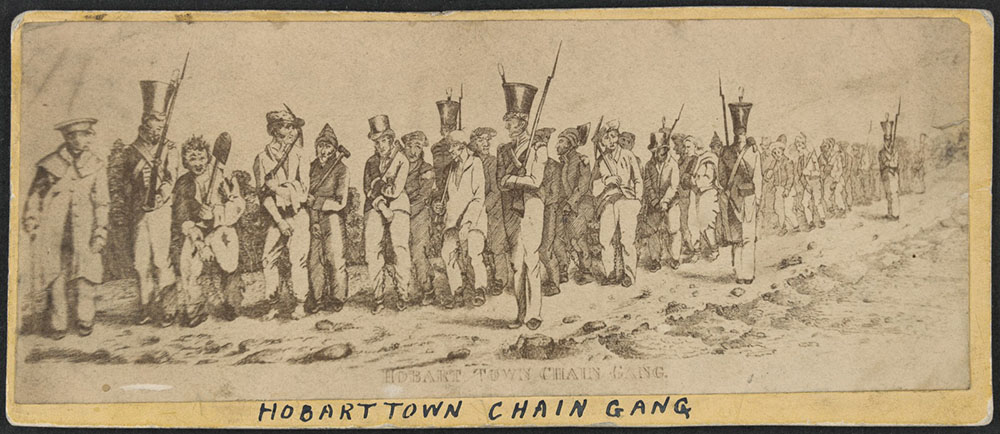

Those who tried to abscond and failed, or flout any of the many other rules and regulations governing their lives were often sent to places of “secondary transportation.” These isolated penal settlements established at Newcastle, Port Macquarie, Moreton Bay and Macquarie Harbour were intentionally harsh. They were places where floggings were frequent, work was backbreaking, living conditions were wretched and life expectancy was short. Norfolk Island would later surpass them all for its brutality.

Australia’s penal settlements were gaols without bars. There was often very little to prevent anyone from taking their leave and hiding out in the bush. But what could they do then? The countryside was wildly unfamiliar, and the already dispossessed Aboriginal peoples were often hostile towards anyone encroaching further onto their land. Despite this, there were several bolters who lived for many years in Aboriginal communities. Alternatively, runaways could hole up on the outskirts of settlements, preying on whoever presented themselves as easy targets. These “bushrangers” were the scourge of early administrators in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. The authorities went to great lengths to hunt them down and bring them to justice, often at the end of a rope. Eking out an existence on society’s fringes was not a viable long-term proposition. Those truly serious about escaping had to look not towards the country’s interior, but out to sea. Where townsfolk, farmhands, labourers and the like viewed the expansive ocean with justifiable trepidation, it was seen in a very different light by the many seamen and mariners in the convict ranks.

Ships had brought them out to the colonies. They could whisk them away. Stowing away was the most frequent method of absconding, especially for those without seafaring skills. A cat-and-mouse game soon developed, with stowaways finding ever more inventive places to hide while the authorities devised new ways of flushing them out. Rarely did a ship leave Australia during the convict era without someone trying to stow away.

For men of a more ruthless and violent temperament, seizing control of a ship and sailing to some far-flung port proved an irresistible temptation. Ships transporting prisoners between settlements were always on alert for trouble, but that did not stop some desperate characters from trying their luck. Captains of vessels, complacent of port regulations, risked their ships being taken by convicts ever vigilant for lapses in security. A few enterprising convicts even built their own craft to make their escape. Few of these endeavours ended well, for the distances to be traversed were vast and the ocean unforgiving to frail and unseaworthy watercraft.

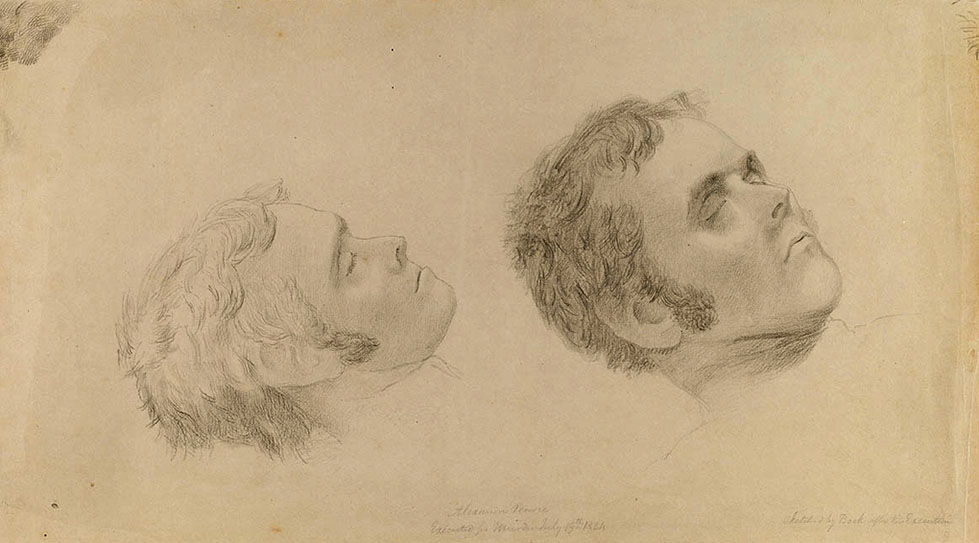

Bolters tells the stories of many of those convicts who chanced their luck to regain their liberty. The narratives draw heavily on the personal accounts left behind by those determined to escape and official reports written by the men whose job it was to stop them. In 1791 William and Mary Bryant and a band of runaways made off with Governor Phillip’s cutter and sailed it to Timor in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). To this day it is still recognised as an outstanding feat of seamanship and survival. It was unfortunate for them that their luck ran out shortly after. However, Mary and a handful of others reached England and were later pardoned. They proved escape was possible, inspiring many others to follow their lead. In 1803, William Buckley fled from a short-lived settlement on the shores of Port Phillip Bay. He was taken in by the local Aboriginal people and remained with them for the next 32 years. Macquarie Harbour saw many inmates try to escape that god-forsaken place. No story is more chilling than that of the infamous cannibal Alexander Pearce and the men who fled into the wilderness with him.

When a group of determined prisoners captured the Cyprus in 1829, few could have imagined that they would sail the vessel to Japan before scuttling it off the coast of China. Several men made it back to England before being arrested. Then, five years later, the prisoners entrusted with completing the Frederick at Macquarie Harbour took off for South America rather than deliver her to Port Arthur as supposed. The book ends with the liberation of six Irish rebels from Fremantle Prison by the American whaler Catalpa in 1876. This was arguably the most carefully planned and executed escape during the convict era. Along the way, the book delves into many lesser-known but no less desperate and dramatic attempts to flee Australian shores.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.