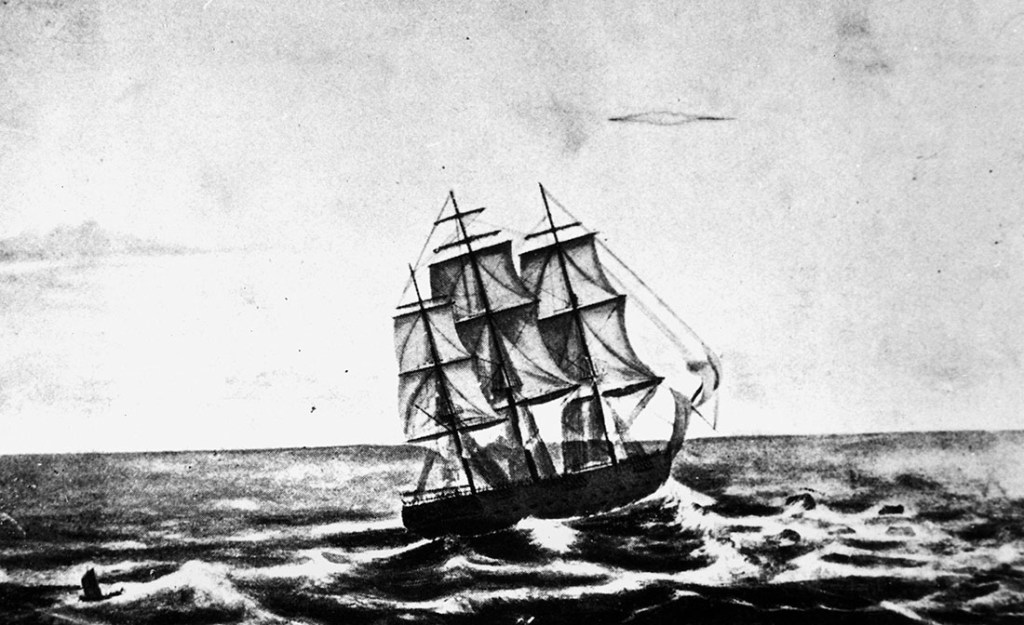

In August 1829, the brig Cyprus sailed from Hobart bound for Macquarie Harbour with provisions and 31 convicts sentenced to serve hard labour at that infamous penal settlement. However, while windbound at Recherche Bay in Tasmania’s south, the prisoners rose up, overpowered their guards and seized control of the ship. Thus began one of the most extraordinary escapes of Australia’s convict era.

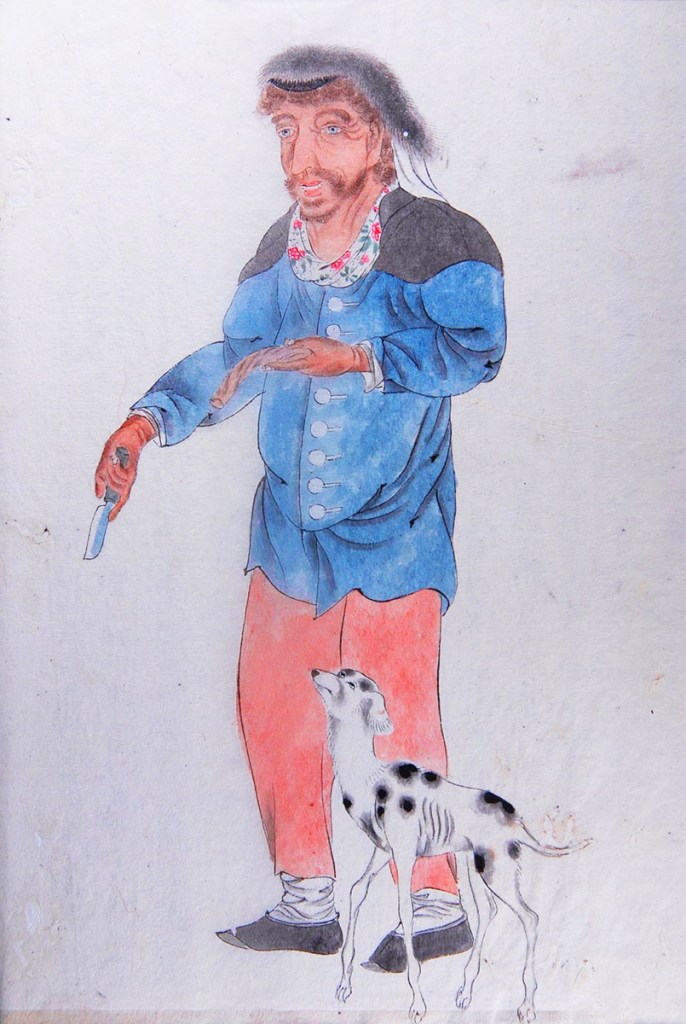

Their leader was a 37-year-old convict named William Swallow. He was likely the only man among the prisoners who had any seagoing experience, so in true pirate tradition, the men voted for him to be their captain. Swallow had once earned a living as a seaman on colliers plying England’s coastal waters. That was until he tired of the seagoing life and found it was more lucrative to break into portside houses or ships moored in harbour. He finally came undone when the police suspected him of being involved in several recent burglaries and raided his house. A large haul of stolen property was found in the house, and Swallow was whisked off to gaol. This took place in 1821 when Swallow was going by the name William Walker. He was found guilty of housebreaking and sentenced to be transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) for seven years.

William Swallow, however, had no intention of going quietly, leaving his wife and three children to fend for themselves. His first attempt to escape took place even before he had left England. He and a fellow prisoner jumped from the ship carrying them to the prison hulks to await the next Australia-bound convict transport. His mate drowned in the attempt, but Swallow survived and returned to his hometown. However, he was quickly recaptured and charged with returning from transportation. This time, he was loaded on a ship and sent to Van Diemen’s Land.

Swallow made a second attempt to escape eight months after arriving in Hobart. He and three other convicts seized a small schooner, crossed Bass Strait and made it to within 80 kilometres of Sydney before they ran aground and were taken back into custody. Swallow received 150 lashes and was sentenced to serve hard labour at Macquarie Harbour Penal Settlement. But he escaped again before ever setting foot in that much-feared hellhole. This time, he escaped from gaol and stowed away on a merchant ship bound for England. There, he lived free until being discovered in 1828. This time, he was sent to Van Diemen’s Land for life. But Swallow was still not ready to give up and accept his fate. Shortly after arriving back in Hobart, he stowed away on the very ship that had so recently brought him from England. By now, guards were masters at finding stowaways, and Swallow was taken off before it left port. He was flogged again and was on his way to Macquarie Harbour on the Cyprus when, in 1829, he and the other convicts seized the ship.

On 13 August, while the Cyprus was windbound in Recherche Bay, the convicts pounced, catching their guards by surprise and wresting control of the ship. They put the soldiers, captain and crew ashore and the following morning, hauled up the anchor, unfurled the sails and gave three hearty cheers as they got underway. The castaways would remain stranded in that remote and inhospitable corner of Tasmania for two weeks before they were discovered. That gave Swallow and his men ample time to get far away from Van Diemen’s Land before the alarm was raised.

It was supposed by the authorities that the runaways would try to make their way across the Pacific, where they would scuttle the Cyprus and pass themselves off as shipwrecked sailors at some unsuspecting South American port. But Swallow and the others had another idea in mind as Van Diemen’s Land disappeared over the horizon behind them.

The Cyprus was well stocked with food, for it carried sufficient supplies to see the Macquarie Harbour Penal Settlement through the coming winter months when it was all but cut off from the outside world. Swallow set a course to take them to New Zealand, where the men painted the vessel’s hull black and renamed her the Friends of Boston. Passing themselves off as an American-flagged ship, they then sailed north towards the Friendly Islands, known today as Tonga.

However, this leg of their voyage was far from smooth sailing. One man was lost overboard during a powerful storm, and the common purpose that had seen the convicts unite to capture the brig had begun to dissipate. After they reached the island of Tongatapu, present-day Nukualofa, seven men chose to remain there when the Cyprus set sail. Swallow continued north across the equator and eventually reached southern Japan after an impressive voyage of nearly 12,500 km. They pulled into a sheltered bay on the island of Shikoku in January 1830, hoping to resupply with firewood and fresh water. However, at the time, Japan was unwelcoming of foreigners. Despite the language barriers, the Japanese made it clear that the Cyprus had to be gone by sunset; otherwise, it would be fired upon.

Swallow heeded the warning, hoping to resupply somewhere more friendly, but as the sun dipped towards the horizon, the wind dropped and the ship was becalmed. The Japanese coastal battery opened fire as they warned they would, and one of the cannonballs struck the vessel on the waterline. But before any more damage could be inflicted, a breeze sprang up, and Swallow wasted no time getting the ship underway. They followed the Ryukyu Island chain south before crossing the East China Sea, all the time taking on water.

In February 1830, the Cyprus was off the coast of China, near the estuary of the Pearl River (Zhu Jiang River). By now, the leak had worsened, and the pumps had to be manned constantly to keep the ship afloat. Several of the runaways had had enough and wanted to abandon the ship. However, Swallow wasn’t ready to give up on the Cyprus just yet, despite the risk of being discovered by British naval vessels in the area. He hoped they might repair the ship and soon be on their way. However, those wishing to go ashore went below and punched a hole in the hull. They then boarded a lifeboat and left the Cyprus to sink. Swallow and his few remaining loyalists could not stem the steady inflow of water and were forced to abandon the ship a few hours later in the remaining lifeboat and make their way to Canton (Guangzhou).

The unexpected arrival of British subjects in the trading enclave raised the interest of the local East India Company officials. William Swallow was asked to visit their offices, where he was questioned at length.

As news of the seizure of Cyprus had yet to reach that port, Swallow passed himself off as Captain William Waldon and late master of the 200-ton English brig Edward. His story was a mixture of fact and fiction. He said that they had left London on 14 December 1828, bound for Rio de Janeiro and had then rounded Cape Horn and crossed the Pacific to Japan, where they were fired upon. The Edward, he said, had steadily taken on water as he tried to make for Manila, but his ship had finally foundered near Formosa (Taiwan).

He told the East India Company officials that he and his crew had boarded two lifeboats and headed for the Chinese mainland, but on the way, he lost contact with the second boat. On the strength that Swallow, AKA Waldon, had a sextant engraved with the ship’s name in his possession, and he had arrived in a longboat bearing the name “Edward of London,” his story was accepted. The East India Company officials gave Swallow and his men free passage to London on a merchant ship about to depart from Canton. The escaped convicts might just have got away with the subterfuge but for a stroke of bad luck.

A second boat arrived at the docks just days after they left. The men on that boat also claimed to be survivors from the Edward. But their version of the story was at odds with the one provided by Swallow. One of the new arrivals was immediately detained, but the rest fled Canton on an outbound ship one step ahead of the law. Then, two more men from the Cyprus turned up in Canton. They had been found on one of the Ryukyu islands and taken to Canton for questioning. When news of the seizure of the Cyprus finally reached the British enclave, the men in custody were questioned more closely, and they eventually confessed to who they were.

A letter was dispatched to London on the next ship to leave, warning the police to be on the lookout for Swallow and the others. That ship arrived in London before Swallow, and the police were waiting. However, by pure luck, he had disembarked at Margate rather than travel up the River Thames to London. The rest of Swallow’s travelling companions were arrested at the dock, and a couple of weeks later, Swallow was tracked down to a Lambeth boarding house, living under an assumed name.

In October 1830, Swallow and four others stood trial for piracy. The jury found the others guilty as charged, but acquitted William Swallow after he convincingly pleaded that he had been forced to take part in the mutiny against his will. Although Swallow escaped punishment for piracy, there was still the matter of his returning to England illegally. He was once again sent to Van Diemen’s Land, where he died at Port Arthur Penal Settlement on 12 May 1834.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.