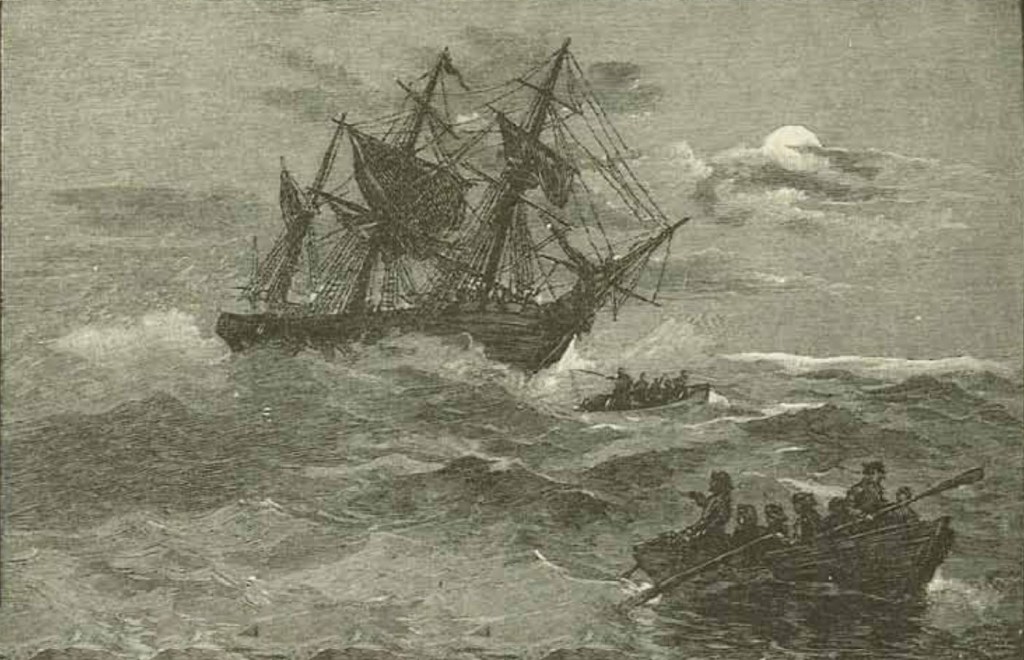

On Sunday, 3 July 1814, the merchant ship Morning Star sailed out of Sydney Harbour bound for Calcutta by way of Torres Strait and Batavia. However, her voyage north ended abruptly on a coral reef south of the Forbes Islands off the far north Queensland coast. The vessel was a 140-ton Calcutta-built brig owned by the Indian-based trading house Lackersteen and Co. When she left Sydney, the crew numbered 37 men, a mix of European and Indian seamen, all under the command of Captain Robert Smart. Only six of them would survive the ordeal.

No account exists of how the ship was lost, but from the location of the wreck site, it appears that Captain Smart was sailing within the Great Barrier Reef when he ran aground and had to abandon ship.

Lieutenant James Cook had charted the route back in 1770, and he had only narrowly avoided total disaster on what he would name Endeavour Reef, some 450 km south of where the Morning Star was lost.

The passage was fraught with danger. Thousands of reefs, many hidden just below the surface, dotted the coastal waters inside the Great Barrier Reef. However, the route had two distinct advantages. Rarely did a ship have to stray far from land, so refuge could be sought should disaster strike. There were also ample safe anchorages where ships could lay up overnight or when the conditions made it difficult to detect hazards lying in their path. Later, mariners would prefer a route that took them far out into the Coral Sea as they made their way north. They would cross the Barrier Reef near Raine Island or other similar narrow passages to pass through Torres Strait. This “outer passage” avoided the labyrinth of reefs but came with its own set of dangers.

On 30 September, the fully rigged Ship Eliza was sailing through Torres Strait when the lookout spotted a white flag flying from a staff on Booby Island. The captain heaved to and sent a boat across to investigate. When it returned, she carried five marooned sailors from the Morning Star. This is the first recorded instance of shipwrecked sailors seeking refuge on Booby Island. Later, it would be stocked with food and water to assist shipwrecked sailors. A primitive post office with a logbook would also be established, so passing mariners could pass on the location of any uncharted reefs they may have discovered.

The castaways had been among 15 men who had taken to the Morning Star’s longboat and made the perilous journey north after abandoning the wreck. They reported that Captain Smart and nine other sailors had left Booby Island five days earlier, intending to make for the Dutch port of Kupang on Timor Island. There is no record of them ever arriving there or anywhere else, for that matter.

The remaining 22 members of the Morning Star’s crew were thought to have perished as a result of the wreck or some calamity that befell them sometime afterwards. But four years later, another Morning Star survivor was found living with the Islanders on Murray Island on the Eastern entrance to Torres Strait.

The Claudine had anchored off Murray Island in September 1818 and sent a jolly boat ashore to meet with the islanders. To the astonishment of all, an Indian sailor was there to greet them in Hindustani. Fortunately, one of the sailors in the jolly boat spoke the language and was able to translate for the others. He told the sailors from the Claudine that he had been on the Morning Star when it ran aground and that since then he had been living with the Murray Islanders. He had learned their language and been accepted into their community, but the circumstances of his arrival on the island and the fate of his shipmates were not recorded. When the Claudine set sail, the Indian castaway was with them.

The Morning Star is just one of many hundreds of vessels, large and small, that came to grief in Queensland’s northern waters from the late 18th and into the early part of the 20th Century.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2025.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.