In July 1846, word reached Sydney that a ship, the Peruvian, had been discovered abandoned on the remote Bellona Shoals far out in the Coral Sea. No one knew what had happened to those who had been on board. As the months passed with no word of any survivors, it was presumed they had all been lost at sea when the ship was wrecked or in a desperate attempt to reach land. Then, 17 years later, a naked lone survivor walked out of the bush with a remarkable story of survival.

His name was James Morrill, and he had been 22 years old in late February 1846 when the Peruvian sailed out of Sydney Harbour on her way to China. Morrill had only joined the crew a couple of days before they sailed. Captain Pitkethly and his crew, including Morrill, numbered 14. Pitkethly’s wife, Elizabeth, six passengers and two stowaways sailed with them. In total, there were 23 people on board.

The Peruvian had fine weather for the first three days and made an easy time of it sailing north under full sails. But during the third night at sea, the weather started to turn. The next morning, the ship was in the grip of a powerful storm. For the next several days, the Peruvian was blown north under bare poles. Then, after nearly a week, the weather began to ease again. Sail was heaped back on, and they started making up for lost time. Then, in the early hours of 8 March, an ominous line of white caps materialised out of the pitch black night directly in their path.

The Peruvian slammed into the reef before there was any chance to change course. The waves lifted the damaged ship onto the reef, where she stuck fast. Seawater swept the deck, washing away the lifeboat and the unsuspecting second mate who had just emerged from below deck.

The morning revealed an unbroken reef awash with turbulent white foaming water as far as the eye could see. No islet, sandbar or refuge of any sort lay in sight. Only jagged rocks jutted from the sea’s surface. Captain Pitkethly made the difficult decision to abandon his ship. When the crew lowered the jolly boat over the side, it was immediately smashed to pieces. They now only had one boat left. It was loaded with supplies and lowered away. Then the ropes got tangled and the boat filled with water. The first mate jumped in the boat to try to save it, but before he could bail it out, the stern broke away. The damaged boat plummeted into the water, and a strong current swept it away from the side of the ship. Resigning himself to his fate, the man bid the captain and crew farewell and was soon lost from sight.

Their situation had become dire with the loss of all three lifeboats. The ship could break apart at any time, and they were stranded over 1000 km off Australia’s east coast. But Pitkethley was not about to give up. The Peruvian’s masts were brought down, and cross planks were lashed and nailed in place, forming a platform. Then the remaining 21 castaways boarded the raft for a very uncertain future.

The raft drifted with the north-westerly current towards the Australian mainland. The days passed slowly under the blazing tropical sun. Water and food were carefully rationed, making thirst and hunger constant companions. Morrill would recall that one day blurred into the next. Had the captain not recorded the passing of each day by carving a notch into a piece of timber, no one could have said how long they had been adrift in that empty sea.

Morrill would later recall that after they had been adrift for a little over three weeks, they had their first casualty from the raft. Captain Pitkethly prayed over the man’s body, and it was lowered into the water. To everyone’s horror, as the body floated away, it was attacked by sharks and torn to shreds. The feeding frenzy, according to Morrill, only ended when the body was completely devoured.

By now, they had probably left the open ocean and were among the shoals of the Great Barrier Reef. Fish could be seen in the crystal clear water, and they were able to catch some with a lure they fashioned from a fish hook, a piece of tin and a strip of canvas. Nature also answered their prayers for fresh water when the skies opened up. Rainwater was collected in a sail, and they could fill their water container for the first time since abandoning the ship. However, their good fortune did not last.

Four weeks of starvation, thirst, and exposure to the elements had taken their toll on everyone. The castaways started dying in rapid succession. “At this time they dropped off one after the other very rapidly, but I was so exhausted myself that I forget the order of their names,” Morrill would later recall.

By now, the raft was continuously circled by sharks drawn by the regular supply of corpses. Half-starved and desperate to fill their aching bellies, the survivors resolved to catch one of their tormentors.

“The captain devised a plan to snare them with a running bowline knot, which we managed as follows,” Morrill would later claim, “We cut off the leg of one of the men who died, and lashed it at the end of the oar for a bait, and on the end of the other oar we put the snare, so that the fish must come through the snare to get at the bait. Presently, one came, which we captured and killed with the carpenter’s axe.”

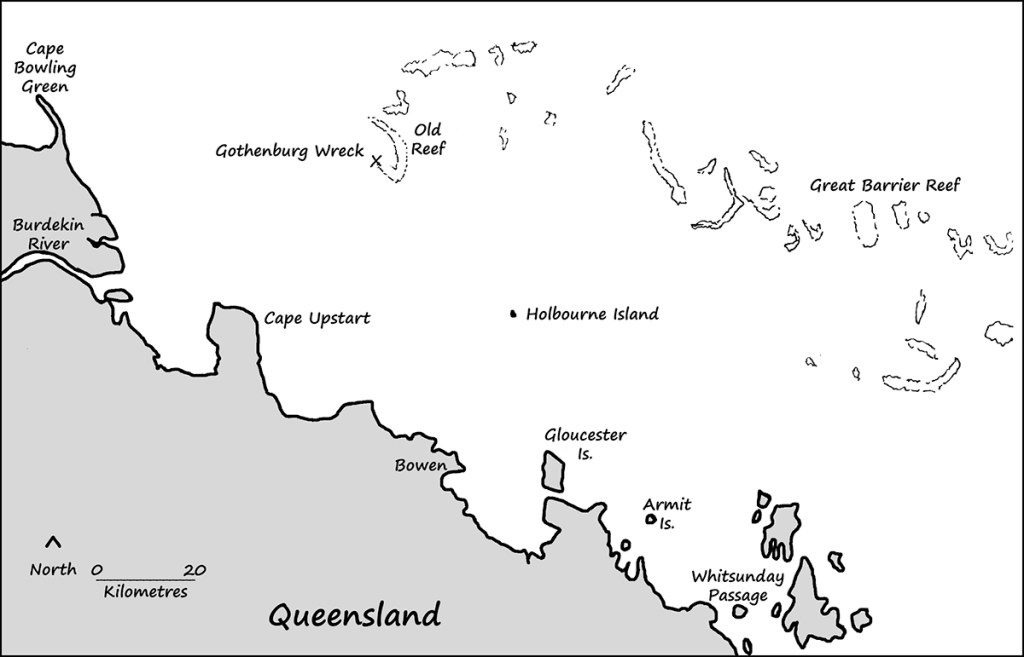

And so Morrill and a few others clung to life. After being adrift for about five weeks, they sighted land for the first time. When Captain Pitkethly examined his chart, he took it to be Cape Upstart. But with no way to steer the raft, they could only watch and pray that they reached shore sometime soon.

“Two or three days afterwards we saw the land once more, and were driven towards Cleveland Bay,” Morrill recalled, “but just as we were preparing to get ashore, in the hopes of getting water, a land breeze sprang up and drove us out to sea again.”

Then, around midnight, the raft washed ashore, likely on the southern point of Cape Cleveland. After so long at sea, no one had the strength to do anything but drag themselves off the raft and collapse on the beach. In the early hours of the morning, it began to rain. Morrill and the other castaways quenched their thirst by drinking directly from shallow depressions in nearby rocks. Cold and wet, they huddled together and waited for dawn.

They had been adrift on the raft for 42 days according to the captain’s tally of nicks in the piece of wood. Only seven of the 21 people who had left the Peruvian were still alive, and two of those would die from exhaustion within hours of reaching land.

For the next couple of weeks, the survivors sheltered in a cave and foraged for shellfish among the rocks. One of the castaways found a canoe pulled up on the beach one day. He would set off south in it alone after Morrill and everyone else refused to join him. Morrill would later learn that his emaciated body was found by Aborigines not far from where he had left.

As their strength slowly returned, the castaways began ranging further afield in search of food. And their presence soon came to the attention of the local Aborigines, the Bindal and Juru peoples. One evening after Morrill and Captain Pitkethly had returned to the cave from a day’s foraging, they heard strange jabbering and whistling sounds. When they went to investigate, they found several naked black men staring at them with keen interest.

“At first they were as afraid of us as we were of them,” Morrill later said. “Presently, we held up our hands in supplication to them to help us; some of them returned it. After a while, they came among us and felt us all over from head to foot. They satisfied themselves that we were human beings, and, hearing us talk, they asked us by signs where we had come from. We made signs and told them we had come across the sea, and, seeing how thin and emaciated we were, they took pity on us. …”

By now, only Morrill, Captain Pitkethly, his wife Elizabeth and a young apprentice were left. They were taken in by the Aborigines and assigned to different groups. The captain and his wife never fully recovered and struggled to adapt to the arduous life among the Aborigines. They died within a few days of each other and were buried together. Morrill would also later learn that the apprentice had also died.

. Morrill would live among the Bindal people of the Burdekin region for the next 17 years. Every so often, his new friends told him that they had sighted a ship out on the ocean, but he was never close enough to try signalling for help. But the sightings served to remind him of his past life.

By 1863, the frontier of European colonisation had reached the lower Burdekin River. By then, he was nearly 40 years old. One day, Morrill approached a hut, calling out to its occupants, “What cheer, shipmates?” The shepherds came out, one of whom was armed with a gun, to find a naked, dark-skinned man standing before them. “Do not shoot me, I am a British object, a shipwrecked sailor,” Morrill yelled. He was invited inside and told the shepherds his story in broken English. He only then realised how much he wanted to return to his old life. Morrill made one final visit to his Bindal family and friends, begging them not to follow him. Aborigines were frequently shot on sight if they seemed to pose a threat, and Morrill did not want that fate to fall on his loved ones.

Morrill would eventually be taken to Brisbane, where he met the Governor. He asked that the Aborigines be allowed to live on their land unmolested by settlers, but his plea went unheeded. He was given a job as an assistant storeman in Bowen, where he married, fathered a child and became a much-liked member of the local community. But the hardships he had endured over the years had taken a toll on his body. An old knee wound, which had never properly healed, became inflamed, and he died, probably of blood poisoning, just two years later. A modest memorial to the last survivor of the Peruvian shipwreck can be found in the Bowen Cemetery.

James Morrill’s full story is told in A Treacherous Coast: Ten Tales of Shipwreck and Survival from Queensland Waters.

© Copyright C.J. Ison, Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

Enter your email address below to be notified of new posts.