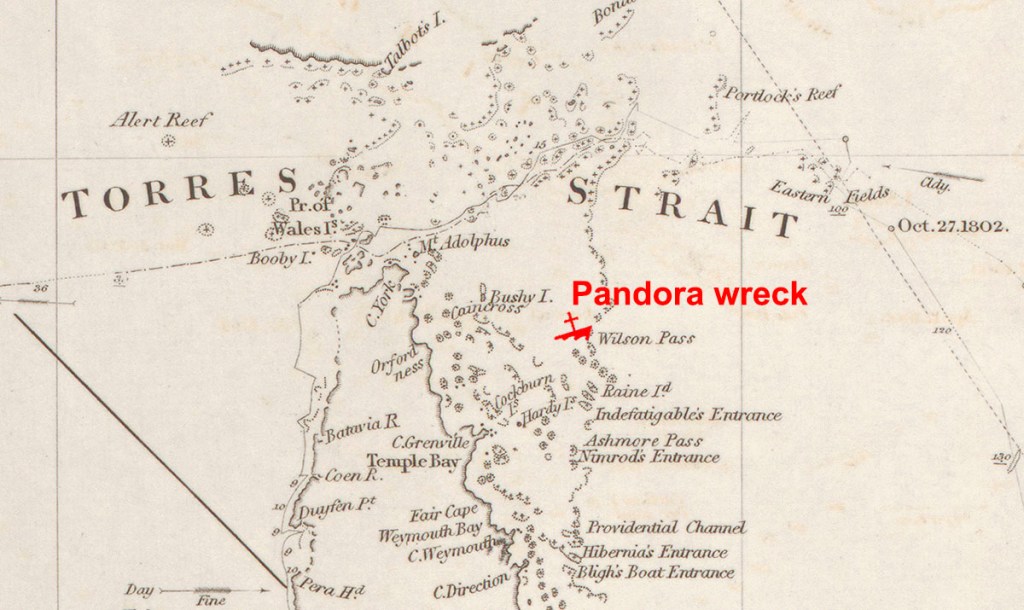

In August 1791, HMS Pandora was returning to England, having tracked down and captured 14 of the Bounty mutineers in Tahiti. But disaster struck on the night of the 29th, as the Pandora was trying to find a way through the Great Barrier Reef. The ship’s surgeon, George Hamilton, left a nerve-wracking account of the incident in his memoir, “A Voyage Round the World in His Majesty’s Frigate Pandora”, published in 1793 after his return to England.

Hamilton wrote that on the night of 29 August, a boat sent earlier in the day by the Pandora’s captain, Edward Edwards, to scout for a passage through the maze of reefs had finally returned to the ship. As the crew was hauling it out of the water, the 24-gun frigate unexpectedly struck a submerged coral reef. Captain Edwards immediately ordered the crew to set the sails as he tried to back off the outcrop, hoping to use wind power alone. When that failed to dislodge his ship, he ordered a boat to be made ready to take an anchor out so he might kedge the vessel off. But by the time the anchor was in place and the crew ready to winch, it was already too late.

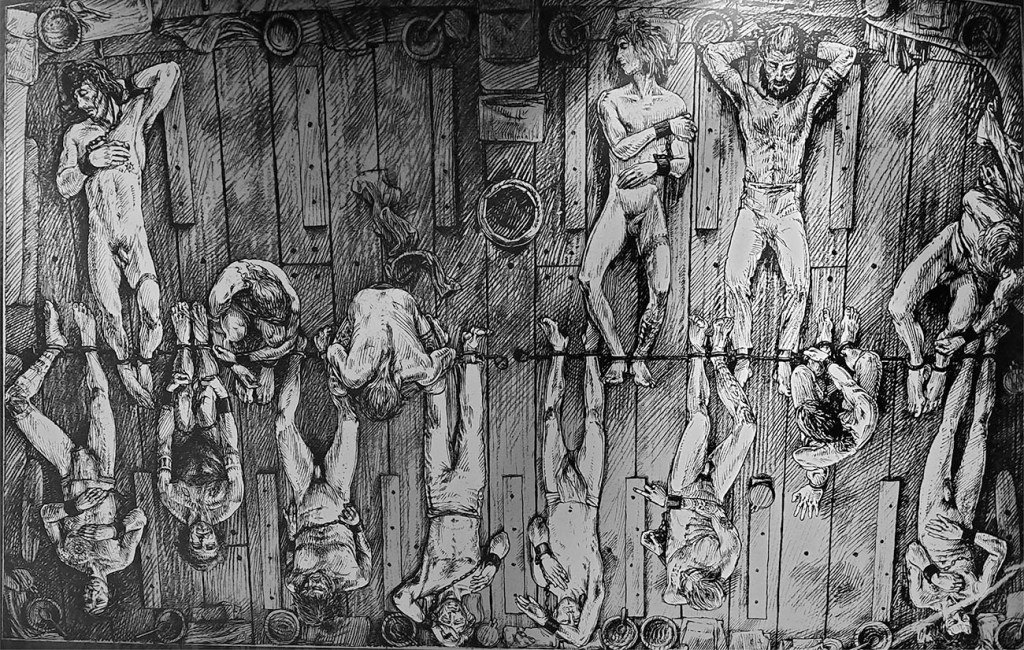

The carpenter had examined the hold and found that the Pandora’s hull had sprung a serious leak. In the 20 minutes they had been aground, the water had risen to nine feet (2.7 m). All hands were immediately engaged in efforts to save the ship from sinking. Sailors began bailing at each of the hatchways, and several of the Bounty mutineers were unshackled to help man the bilge pumps.

“It blew very violently, and she beat so hard upon the rocks, that we expected her, every minute, to go to pieces,” Hamilton recalled. “It was an exceedingly dark, stormy night, and the gloomy horrors of death presented us all around, being everywhere encompassed with rocks, shoals, and broken water. About ten [o’clock] she beat over the reef, and we let go the anchor in fifteen fathoms of water.

Not yet ready to give up on his ship, Captain Edwards ordered the guns thrown overboard and, at the same time, had some of his men prepared the topsail to be hauled under the ship’s bottom in a vain effort to stem the leak. But before they could get the sheet of canvas over the side, one of the bilge pumps failed, and the water began flowing into the hold faster than it could be bailed out. The topsail was abandoned as every hand was set to work, baling to stop the ship from sinking.

Soon the Pandora began listing, and the crew experienced their first casualties. A canon broke loose and rolled across the deck, crushing a sailor, while a topmast came crashing down on deck, killing another. The crew laboured at the pumps and bailed with buckets through the night to keep the ship afloat. An ale cask was tapped, and its contents were regularly served out to the men to keep their spirits up.

Then, about half an hour before dawn, Captain Edwards called his officers together to discuss their next move. It was clear to all that the ship was doomed and that their efforts should shift from saving the ship to preserving the lives of the crew. The Pandora’s four boats had been put over the side earlier in the night, and they were sheltering in the lee of the reef, their coxswains awaiting further orders. Spars, booms, hen-coops and anything else that floated were cut free so that the men might find something to keep themselves from drowning when the ship inevitably sank.

Hamilton wrote that Captain Edwards ordered that the remaining prisoners be released from their irons. However, it came too late for some of the mutineers who were still shackled in place in their makeshift prison they called “Pandora’s Box.” They went down with the ship.

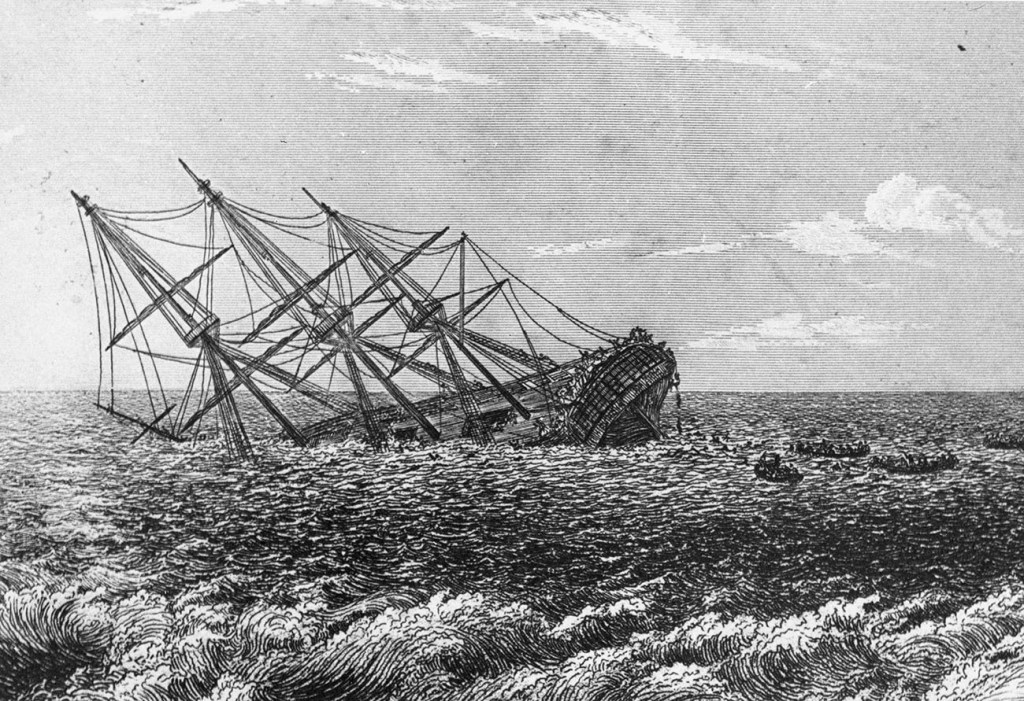

The water began pouring in through the gun ports, causing the frigate to list even further. As the captain and crew scrambled to jump overboard, the Pandora heeled over and sank almost immediately. The boats came to the rescue of the sailors clinging to the wreckage in the water, but for many help came too late. “The cries of the men drowning in the water was at first awful in the extreme,” Hamilton wrote. But as the men disappeared below the surface, the screams faded and then died away entirely.

As morning heralded a new day, a small sandy cay could be seen about two and a half nautical miles (5 km) to the southeast. Edwards ordered the boats to make for the one tiny speck of land in that vast expanse of sea. The captain took stock of their provisions and ordered a guard to be placed over the remaining surviving mutineers. Fortunately, someone had the forethought to load a barrel of water, a small keg of wine, and some sea biscuits onto one of the boats. To that haul of supplies could be added a few muskets and cartouche boxes of ammunition, along with a hammer and a saw. Not much to preserve life in such remote and hostile waters. Edwards thought their only chance of survival would be to make for the Dutch trading outpost on Timor Island, some 1200 nautical miles (1400 km) away.

Edwards forbade anyone from drinking on that first day, calculating that they would have only enough water to last 16 days at two small cups per person per diem. They spent two days on the cay preparing the boats for the voyage that lay ahead. Floorboards were torn out and affixed to the sides of the boats, around which canvas was wrapped to increase the freeboard.

Before leaving, the sailing master, George Passmore, was sent back to the wreck site to see if anything might have floated free in their absence. He returned two hours later with a small assortment of salvaged materials and a cat that he found clinging to the top-gallant mast-head.

On the third morning, they set off west towards Torres Strait and beyond to the Dutch settlement of Kupang. Edwards had hoped to refill their water cask at one of the islands dotting Torres Strait before they headed into the expanse of the Arafura Sea. However, an encounter with Islanders, which began friendly enough, inexplicably ended abruptly with a volley of arrows and musket fire being exchanged. They stopped again at Prince of Wales Island (Muralag), where this time they were able to fill their water cask without incident. On 16 September, after an arduous voyage lasting about a fortnight, the four boats pulled into Kupang Harbour. From there, they were taken to Batavia (present-day Jakarta), where Edwards purchased a ship for the return to England.

The shipwreck directly cost the lives of 31 sailors and four mutineers. Another 16 died from disease during or after their stay in Batavia. Of the 134 men who left England on the Pandora, only 78 made it home alive. The ten prisoners who survived the wreck were tried for mutiny. Four were acquitted, two received pardons, one got off on a technicality, and three were hanged. Captain Edwards faced a court-martial to answer for the loss of his ship, but he was found not to have been at fault.

The Museum of Tropical Queensland in Townsville has a world-class exhibition of artefacts recovered from the wreck.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.