On the night of 2 October 1797, fourteen convicts stole a boat and made their way down the Paramatta River across Sydney harbour and out through the Heads. When the men were discovered missing, the authorities sent boats in pursuit, but they returned a few days later, having never caught sight of the runaways. As a storm had swept the area shortly after they had escaped, it was thought the bolters had died at sea. However, that was no more than wishful thinking. Their story is one of desperation, betrayal, and ultimately defeat.

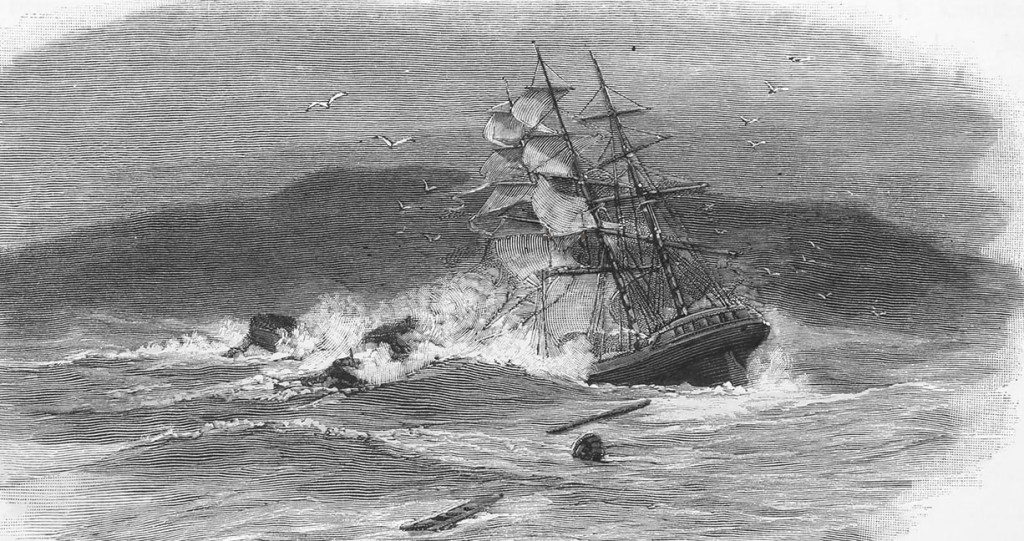

The runaways’ leaders were John Boroughbridge and Michael Gibson. They had been labouring away in the back blocks of Paramatta when they convinced 12 other desperate men to join them in an audacious escape. Their plan was to find the remains of the 250-ton Sydney Cove, a ship that had recently been wrecked somewhere far to the south of Sydney. Boroughbridge and Gibson were sure they could build a new vessel from the timbers and fittings and make for some distant port far from the clutches of British law. That the Sydney Cove had been carrying a massive cargo of rum and other alcoholic spirits added to its allure.

Boroughbridge was serving 14 years for some unspecified crime and had landed in New South Wales only four months earlier and was keen to leave at the first opportunity. Gibson had already spent five long years there, but with nine more to serve, he was no less eager to put the place behind him. It seems they had little difficulty finding 12 others willing to join them.

With nothing more than a small pocket compass and the knowledge that the wreck lay somewhere far to the south, they headed out through Sydney Heads and turned right. A day or so later, the weather turned nasty, but Boroughbridge and his mates ploughed on. Twice, their boat was driven ashore, and both times, they were lucky to avoid serious damage.

In time, the weather eased, and they continued following the coast and unknowingly strayed into Bass Strait. In 1797, no one knew that a body of water separated Van Diemen’s Land from the rest of Australia. All Boroughbridge and the others would have known was that the Sydney Cove was aground on an island somewhere off the coast. They likely had no accurate idea how far they had come or how much further they had to go. They certainly could not have known that they needed to cross 200 km of open water to reach the beached ship. By now, the compass would have shown that they were heading in a south-westerly rather than southerly direction as they doggedly follow the contours of the coast.

Finally, they ran out of food and fresh water. In desperation, they put ashore on one of the small islands in the vicinity of Wilson’s Promontory. There, they found a ready supply of fresh water, while seabirds and seals made easy prey for the starving men. But, the trying conditions took their toll. By now, many of the runaways would have gladly returned to Sydney to face any punishment short of death if it meant an end to their suffering.

Any sense of common purpose they may have once possessed had since evaporated. They could not agree on what they should do next. Should they stick to their original plan and continue searching for the elusive Sydney Cove? Or should they abandon the search and head back north? Then, one night, in a callous act of betrayal, Boroughbridge, Gibson and five others quietly set off in the boat, abandoning the rest of the men as they slept.

After leaving their comrades to their fate and giving up the search for the Sydney Cove, they returned north again. Bypassing the entrance to Sydney Harbour, they continued on to the mouth of the Hawkesbury River, where it emptied into Broken Bay. It cannot have been lost on the weary men that after three or four months on the run, they were now barely a day’s sailing from where they had started.

After months at sea, their boat was in such a derelict state that they did not trust it to carry them any further. The men agreed they would continue sailing north, but to do so, they would have to find another boat. They did not have long to wait.

Boroughbridge and his men seized a passing vessel and set a course north. Their plan now was to make for Timor in the Dutch East Indies as William Bryant, his wife Mary and others had done some six years earlier. News that Mary and some of the other runaways had reached England and been pardoned had only recently reached Sydney offering hope for anyone contemplating following in their wake.

Nothing more was heard of them for another couple of months. Then, in late March 1798, they returned to Broken Bay and hailed down a passing boat. Boroughbridge handed a letter to the boatswain asking him to deliver it to the NSW Governor. The letter, signed by Boroughbridge, Gibson and three remaining runaways, claimed they wished to give themselves up and begged for clemency. They wrote that they had sailed about 400 nautical miles (750 km) north, which would have put them on either Stradbroke or Moreton Island. Then, they claimed, disaster struck. When they tried to run ashore, their boat was caught in the surf and driven hard onto the beach, where it broke apart with the pounding of successive waves. They were stranded on an inhospitable stretch of coast. But all was not lost. They were able to salvage enough timber from the wreckage to build a smaller craft and put back out to sea. However, by now, they had all had enough of life on the run. They decided that rather than continue sailing north, they would return to Sydney and beg for mercy.

Their plea for mercy fell on deaf ears, for the Governor had learned that Boroughbridge and the rest of the men seeking clemency had callously abandoned half their mates to die on the island in Bass Strait. In an unlikely turn of events, they had been found by George Bass while he was endeavouring to prove the existence of the body of water which now bears his name. Unable to carry all seven back to Sydney on his small boat, he ferried five across to the mainland, gave them a compass, a musket and as much food as he could spare and told them to follow the coast north to Sydney. They were never heard of again. Two men, too weak to walk, remained with Bass. He returned to Sydney on 25 February and handed the pair to the authorities and they reported what had befallen them.

In April, Boroughbridge and the four remaining runaways were returned to Sydney, where they were tried for piracy and found guilty. Jonathon Boroughbridge and Michael Gibson were hanged, while their three companions were only given clemency at the last minute as they stood before the gallows contemplating their final moments of life.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.