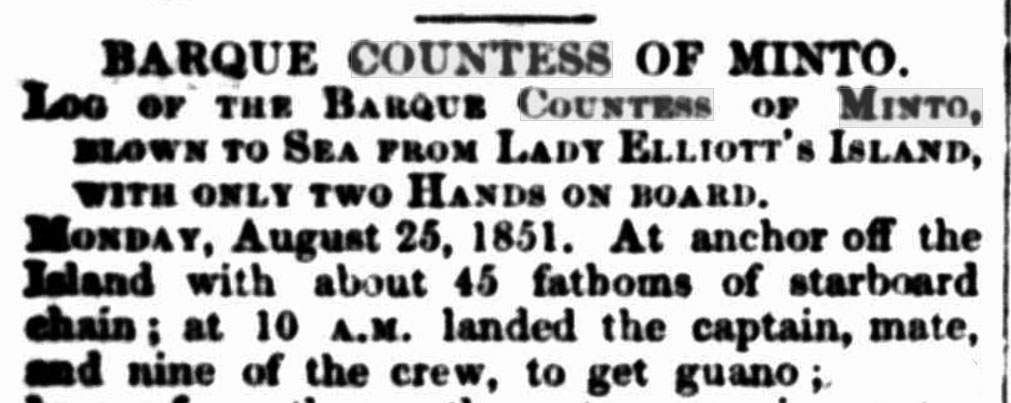

On 12 July 1909, the mail steamer Tofua was passing Middleton Reef in the Coral Sea bound for Sydney. Captain George Holford gave the order to steam close by as was his want every time he passed. This time, he noticed a new ship’s carcass had been added to the dangerous reef since he had seen it last. Since the Britannia Godspeed ran aground on Middleton Reef in 1806, it and neighbouring Elizabeth Reef have claimed over 30 ships and countless lives over the years.

Captain Holford steamed as close as he dared, then had a boat lowered to go across and investigate. As the steamer neared the reef, he also noticed that some rags were flying from the mast of another ship, the Annasona, which had been wrecked two years earlier.

The boat soon returned with five survivors from the Norwegian barque Errol, which had run aground a month earlier with 22 souls onboard. They had a tragic tale to tell.

The Errol had left the port of Chimote in Peru on 15 April, with a crew of 17 men and five passengers, comprising the Captain’s wife and four children. The barque was headed to Newcastle to take on a cargo of coal. However, disaster struck around midnight on 18 June when, without warning, the barque slammed into Middleton Reef.

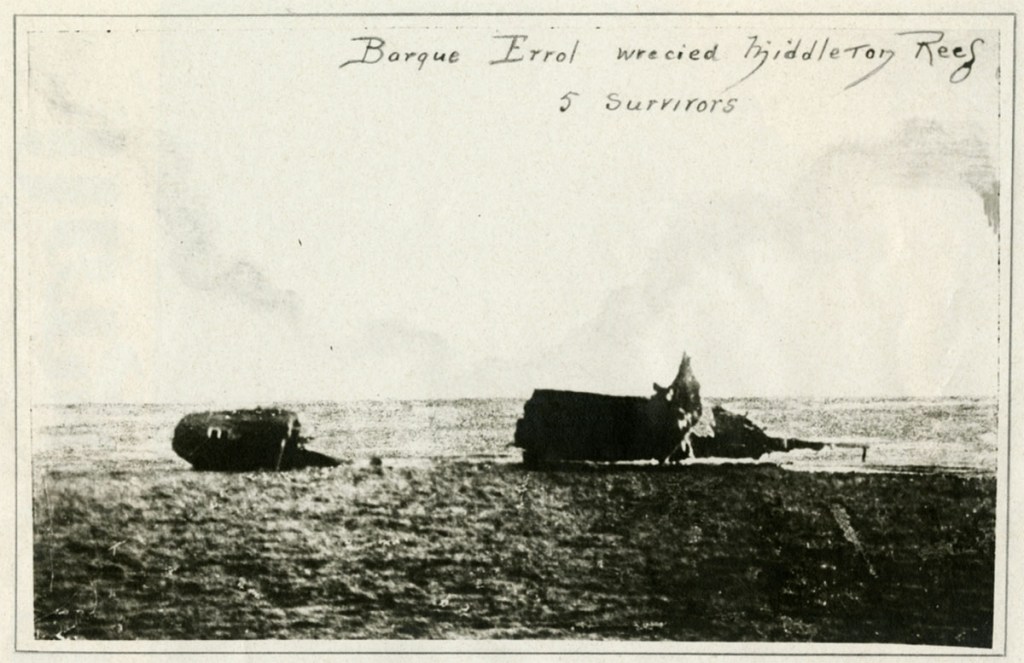

The ship was swung broadside to the reef before there was even a chance to try and save her. The hull was torn out, and she rapidly settled with a heavy list to starboard. Powerful waves swept over her, ripping apart the houses and washing away much of their stores along with the ship’s lifeboats. She quickly succumbed to the pummelling and broke into four separate parts.

The First Mate was swept away and drowned as he and one of the crew tried vainly to clear one of the lifeboats. Two more seamen also died that first night or on the second, the survivors could not recall. Captain Andreason and the Second Mate were lost a couple of days later. They had been on the reef, not far from the ship, building a raft comprised of spars and other timbers when they were caught by the rising tide. Though they tried to swim back to the Errol, the current was too strong and they were washed away. The Captain’s wife and children could only look on in horror.

The survivors were in dire straits. The only food they had been able to salvage was a dozen loaves of bread, a few pounds of butter and a couple of tins of milk. What’s more, they had precious little fresh water. A shelter of sorts was constructed on the exposed hull for the Captain’s wife and her children while the sailors made do with a canvas sail for protection from the elements.

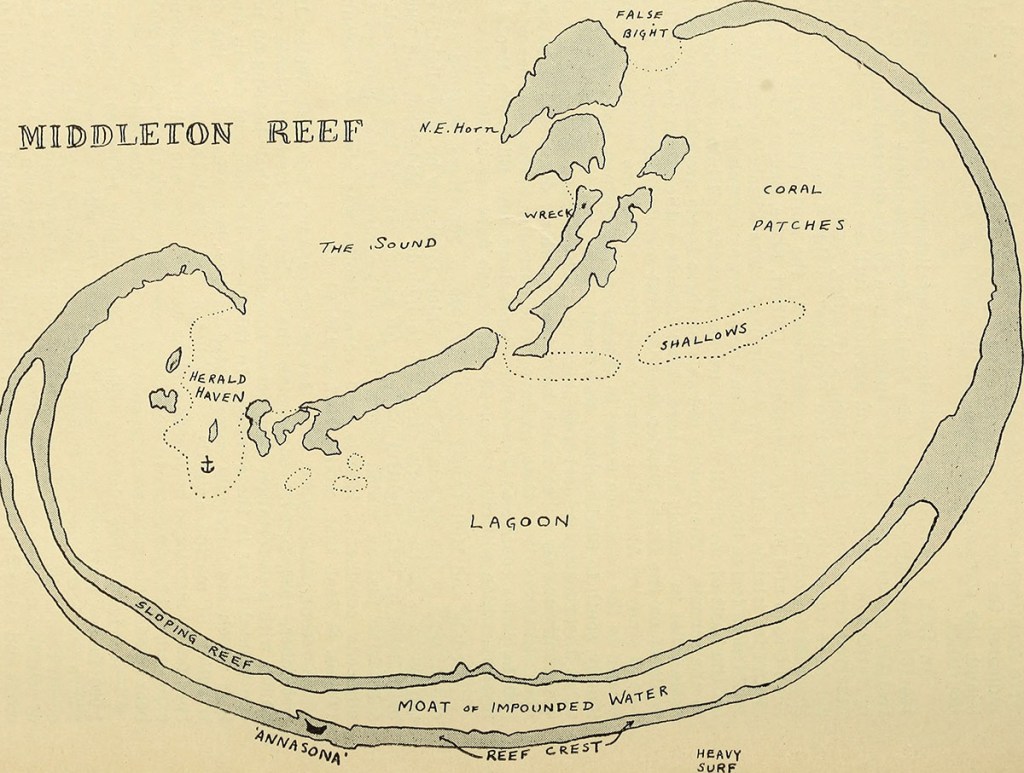

Meanwhile, they continued to work on the raft. After a few days, it was completed, and five of the crew set off for the Annasona, about 8 miles, 15 kilometres away, hoping they might find food and water.

The raft barely held together long enough to reach the long-abandoned ship. Fortunately, they found some fresh water, but the only sustenance available was shellfish clinging to the side of the wreck and the reef it stood on. They spent 12 days on the Annasona building a more substantial craft to get them back to the Errol and their shipmates. But before leaving, they hoisted a couple of shirts up the mast. They had seen one ship pass by during their time there, but it had failed to see them or their signal of distress. One of their number perished on the expedition across to the Annasona; however, a far greater tragedy had played out among those waiting on the Errol.

When they climbed back aboard the Errol, they found only one man alive, Able Seaman Jack Lawrence, and he was barely clinging to life. They had survived on a small amount of rain collected in the sails, but it proved almost as salt-laden as seawater. Lawrence described how the others, including the Captain’s wife and children, had passed away one by one from thirst, starvation and exposure. As each person died, their body was pushed over the side to splash in the sea. At least some of those corpses had been savaged by sharks, leaving the grisly spectacle of bones or body parts deposited on the reef at low tide.

All five men would likely have died on Middleton Reef had Captain Holford not made his customary search for castaways. They were returned to his ship and cared for until they arrived in Sydney. At a time before any sort of public safety net, the Tofua’s passengers generously donated over £100 to assist the shipwreck survivors get back on their feet.

An inquiry into the tragedy heard that the Errol had experienced several days of overcast weather, where no astrological sightings could be made. They were essentially sailing blind when they struck the reef. One of the survivors also claimed that Captain Andreason had not taken the precaution of sending a lookout aloft to warn of any hazards in their path.

For his act of humanity in rescuing the Errol survivors, Captain George Holford of the Tofua was later presented with an engraved silver coffee service by a grateful Norwegian Government.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2025.