In September 1877, a most unusual-looking vessel left the Egyptian port of Alexandria bound for England. She was the brainchild of engineer John Dixon and had been purpose-built to carry a 200-ton stone obelisk to London. “Cleopatra’s Needle”, as it became known, had been gifted to Great Britain almost sixty years earlier, but until Dixon came along, no one had found a cost-effective way of transporting the massive monolith to its destination on the banks of the Thames River.

The obelisk had originally been erected at Heliopolis near present-day Cairo in 1450 BCE on the orders of Thutmose III. Two hundred years later, Ramses II added inscriptions commemorating his victorious battles. Then, in 12 BCE, Cleopatra had it, and a second obelisk carried down the Nile to Alexandria and installed outside a temple to Julius Ceasar and Mark Antony, where they were eventually lost to time.

While visiting his brother in Egypt in 1875, Dixon devised a plan to get the needle to London. There had been a couple of schemes suggested in the past. One proposed dragging the heavy monolith through the narrow streets of Alexandria to the port where it could be loaded onto a ship. Another was to dredge a channel from the waterfront to get a ship alongside the monolith where it lay. Neither was particularly economical or practical. But, after taking a look at the obelisk in situ, Dixon thought he had the solution.

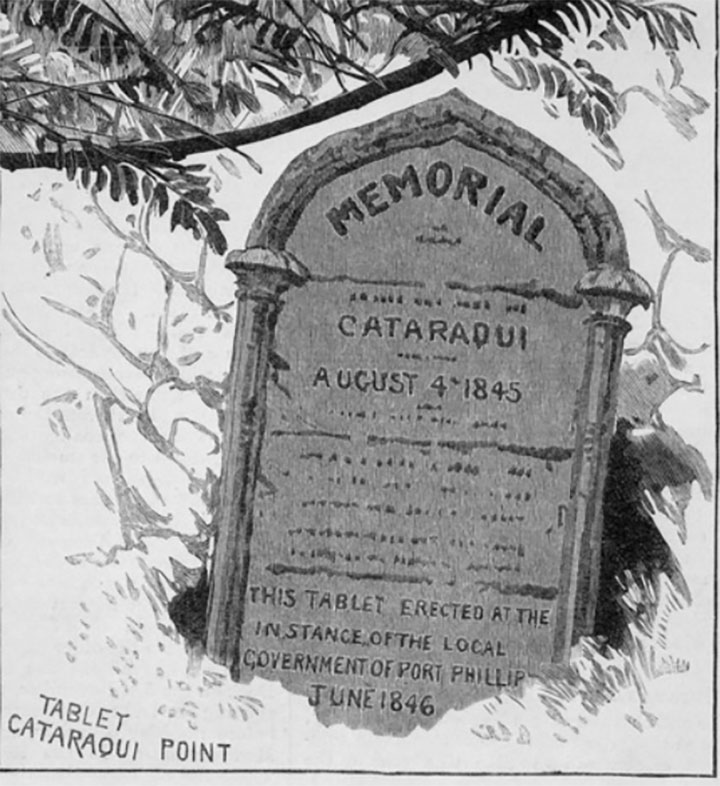

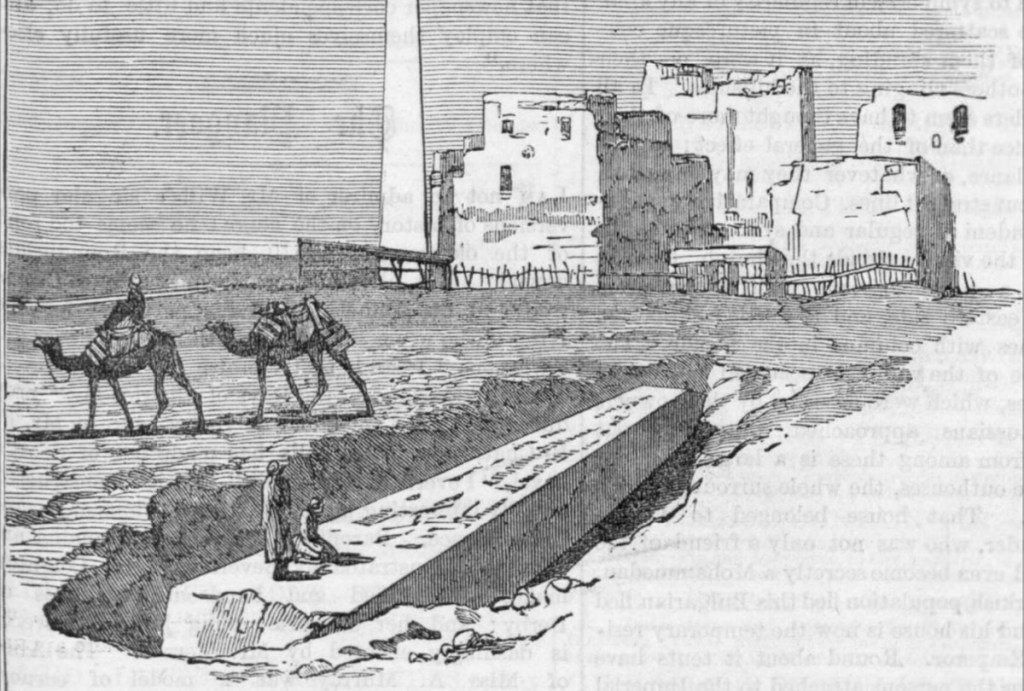

The obelisk was lying on its side, covered in sand behind an old quay wall about 4 metres above sea level. On the seaward side of the wall, the sand sloped down gently to the water’s edge, eventually reaching deep water a few hundred metres away. Rather than move the obelisk to a ship, Dixon proposed building a cylindrical vessel around Cleopatra’s Needle and, after removing a portion of the quay wall, rolling it down the slope and into the sea. He estimated the venture would cost no more than £5,000 to get it to London and another £5,000 to have it installed on the Thames Embankment. The cost was a far cry from the £80,000 the French had apparently paid to have one delivered to Paris in the 1830s.

With the government showing no interest in wearing the cost, it was up to private enterprise to come to the fore. Dixon even offered to contribute 500 guineas of his own money to get things started. But after two years of stagnation, a benefactor in the form of the noted surgeon and philanthropist Professor Erasmus Wilson stepped forward and donated the full amount.

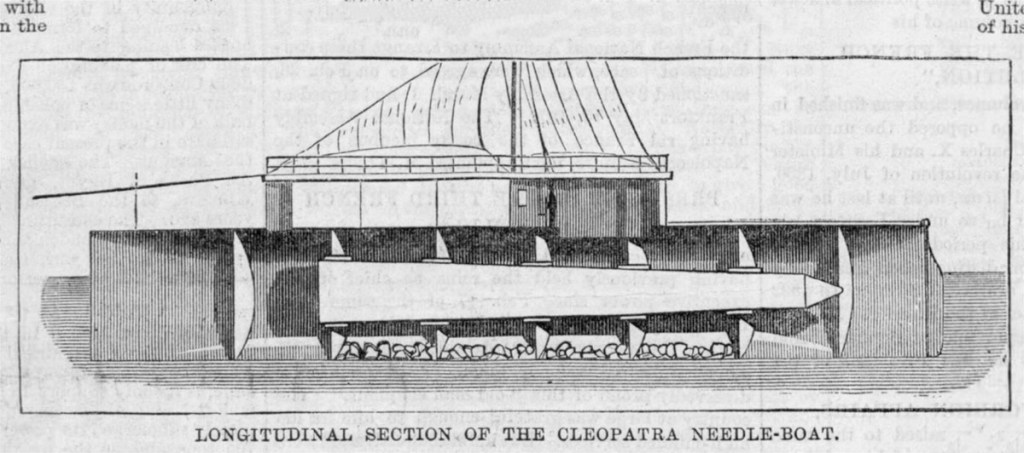

By May 1877, Dixon was back in Alexandria and had begun work excavating around the buried obelisk. It measured nearly 21 metres long and was slightly over 2 metres wide at the base. He began encasing it in an iron cylinder 28 metres in length and 4.5 metres in width. To prevent the stone and hieroglyphs from being damaged, Cleopatra’s Needle was cradled by several iron interior bulkheads lined with timber.

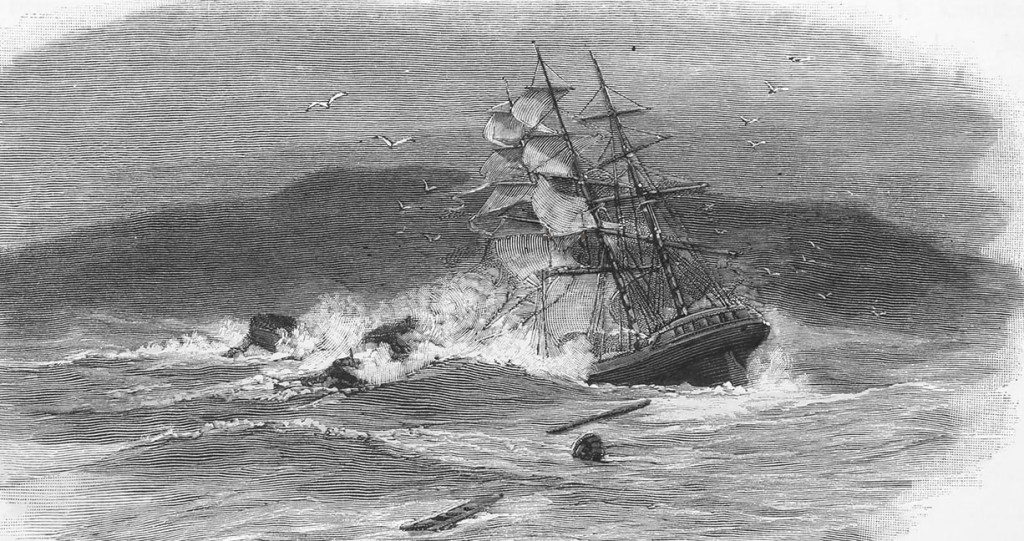

The vessel resembled a giant cigar tube and was now ready to be floated. A path was cleared and it was rolled towards the sea. However, when tugs took the tube in tow, they discovered she had filled with water. A stone had punctured a plate while the tube was being rolled down the beach. The damaged plate was repaired, and the tube pumped dry. Ballast was added, and the odd vessel was towed to a waiting dry dock where the rest of the work would be completed.

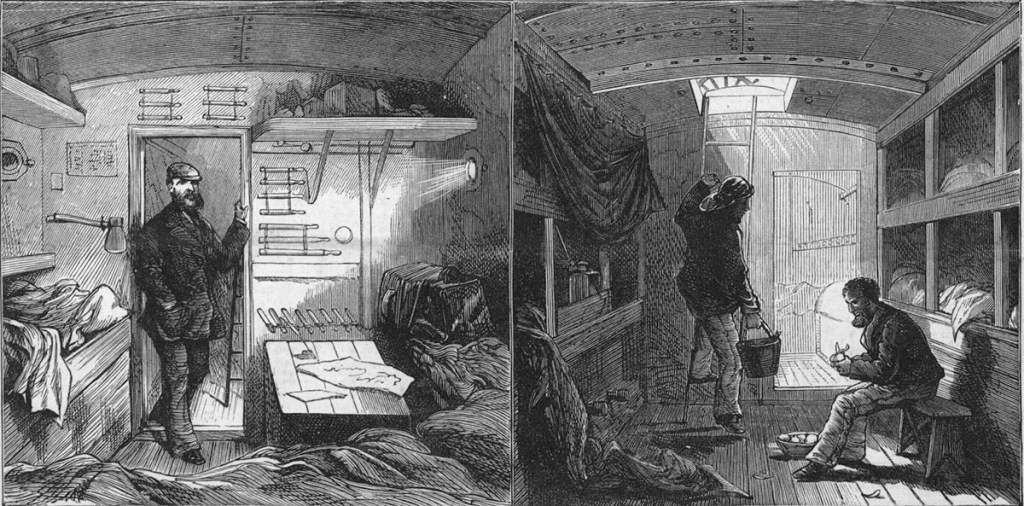

A cabin large enough to accommodate four men was mounted on the top of the tube and a keel below. A stumpy mast and rigging were installed, along with a rudder, wheel and associated running gear. The Cleopatra, as she was named, was ready to make the 6000-kilometre voyage to London. Not having the means to propel herself, she was to be towed to England by the steamer Olga. The sail and steering gear were only fitted to ease the strain on the steamer.

On Friday morning, 21 September, Captain Booth gave the order for the Olga to get underway. As she cleared Alexandria Harbour, the Cleopatra followed in her wake, tethered by a pair of tow cables. They chugged along at a steady six knots, which was about as fast as the Olga could go towing her cumbersome load. It cannot have been a pleasant cruise for Captain Campbell and his men on the Cleopatra. At first, she yawed terribly, pulling one moment to port and the next to starboard. However, once the Cleopatra’s steering chains were tightened and the towing cables lengthened, she finally ran true behind the steamer. However, that did not stop her tendency to porpoise. Dixon, who was travelling on the Olga, wrote, “I have counted as many as 17 times a minute that her nose has been underwater, and then ten or twelve feet above.”

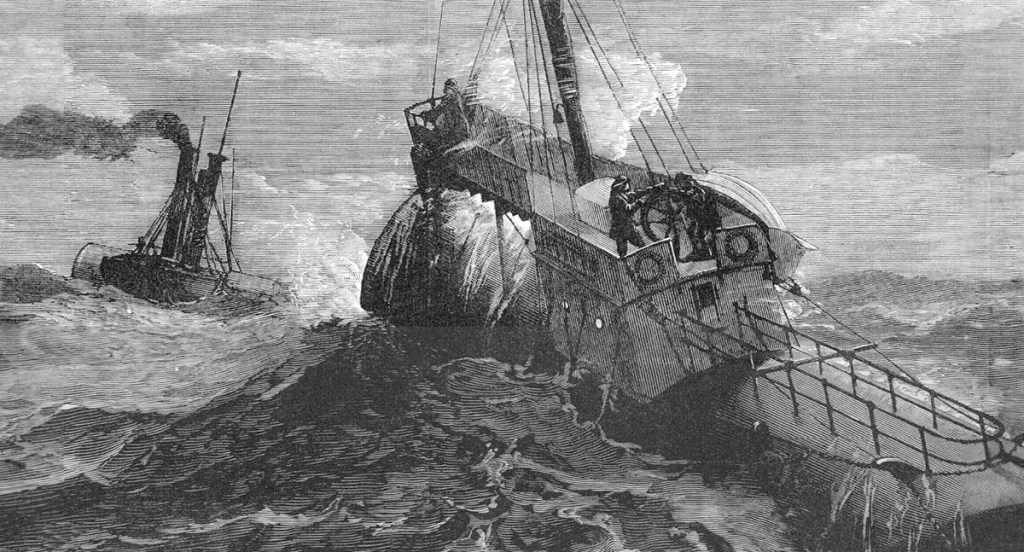

Apart from a few minor leaks, which were quickly plugged with cement, the voyage was uneventful until they were about to cross the Bay of Biscay. On Sunday, 14 October the Olga and the Cleopatra were off Cape Finisterre when they were caught in a violent storm. They were lashed by huge seas and a Force 7 to 8 gale blowing from the southwest. That night, the Cleopatra’s ballast shifted and she was thrown onto her beam ends. Captain Campbell cut away the mast, but the vessel did not right herself. With the Cleopatra floundering around at the mercy of the wind and the waves, Campbell fired off his distress flares. Captain Booth sent six men across to help in any way they could, but they were lost in the maelstrom before they reached the heavily listing vessel. Eventually, Campbell and his men climbed into a boat and were hauled across to the Olga with the aid of a rope.

Captain Booth had no choice but to cut away the Cleopatra as he went in search of his six missing crew. After spending some time searching the seas, the effort was abandoned, and the Olga headed for Falmouth to report the tragedy. However, a couple of days later, the Cleopatra was found adrift about 170 kilometres off the Spanish coast by the crew of the Scottish steamer Fitzmaurice. They had been en route from Glasgow to Valencia when they happened upon the strange vessel bobbing in the water. They took it in tow and delivered it to the Spanish port of Ferrol and reported their find to the British Vice-Consul.

Dixon offered the salvors £500 for finding the Cleopatra and its priceless cargo and taking her to port. However, the Fitzmaurice’s owners claimed salvage rights ten times that amount. The case eventually headed to the Admiralty Court, where the sum of £2000 was decided upon. Meanwhile, the Cleopatra was towed the rest of the way to England, and up the Thames River to London, where it was to be installed on The Embankment. There, the Cleopatra’s hull was opened up, and the obelisk removed none the worse for its long sea voyage. Cleopatra’s Needle was erected on a new plinth where it still stands to this day. A plaque commemorates the six men who lost their lives trying to save the Cleopatra and her crew.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.