In 1890 Queensland experienced one of its worst maritime disasters when the passenger steamer Quetta sank in Torres Strait in just three minutes with the loss of 133 lives.

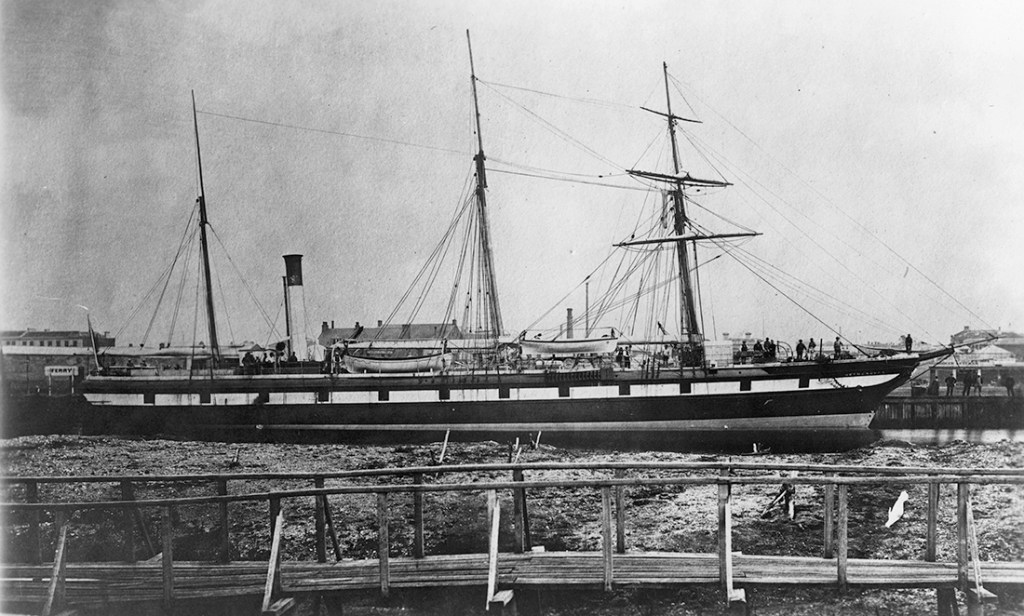

The R.M.S. Quetta was a 3,300-ton coal-powered, iron-clad steamer measuring 116 metres (380 feet) in length and could travel at a top speed of 13 knots (24 kms per hour). She was built in 1881 and on this voyage from Brisbane to London she carried nearly 300 people – passengers and crew.

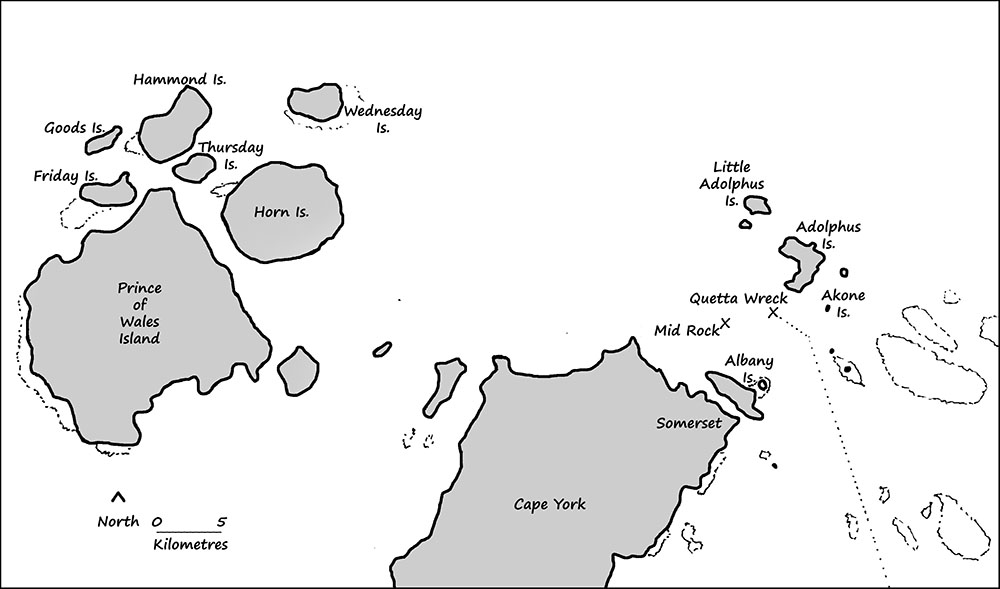

At 9.14 on the evening of 28 February a sharp jolt and a shudder ran through the Quetta as she was being piloted through the Albany Passage. Initially, the pilot and captain were more perplexed than alarmed. The pilot was sure they were miles from any known hazards and it didn’t feel like they had hit anything substantial. None-the-less Captain Sanders followed protocol and ordered the engines stopped, the lifeboats got ready and the carpenter to sound the wells.

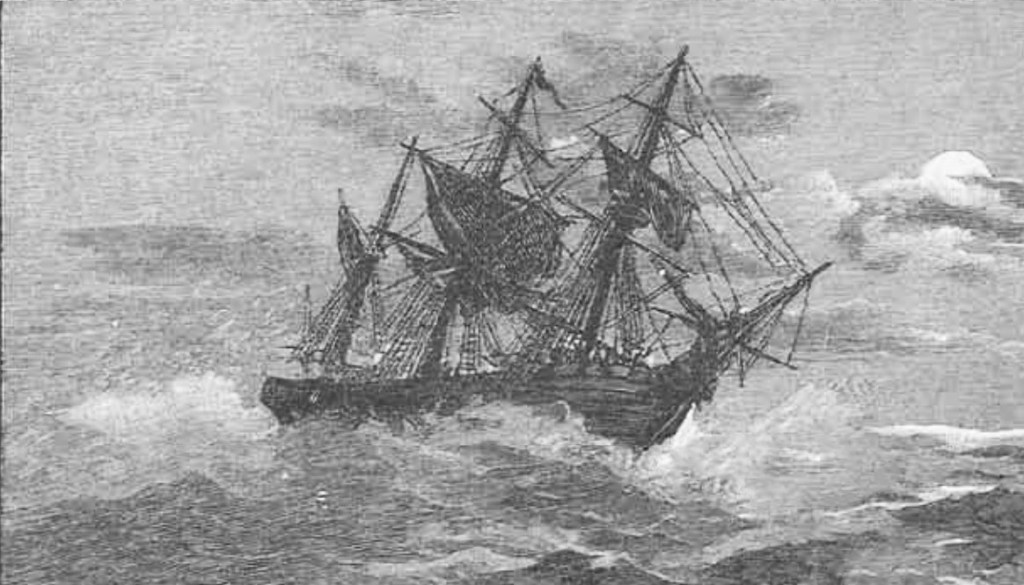

Moments later the carpenter cried out “she’s sinking.” Water was pouring into the ship at an unimaginable rate. What no one realised at the time was they had struck an uncharted rock pinnacle right in the middle of the main shipping channel through Torres Strait. A gapping hole had been torn in the Quetta’s hull from bow to midship one to two metres wide.

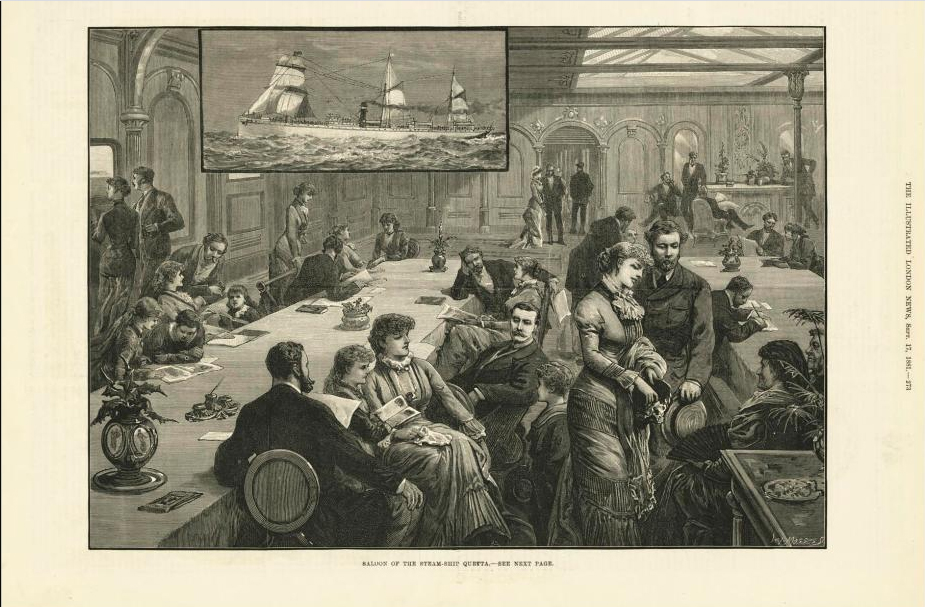

The ship was already starting to settle by the bow as Captain Sanders ran aft encouraging passengers to make their way there. At the time many of the first-class passengers were in the saloon rehearsing for an upcoming concert and were oblivious to what was taking place outside. The crew were still frantically trying to get the lifeboats out when water began lapping at their feet only a minute or two later.

Then the stern reared up out of the water and the ship plummeted below the surface of the sea spilling scores of people into the water. Many others were trapped in the saloon, their cabins or under the ship’s sun awnings and drowned.

The Quetta sank in just 3 minutes. Most of those who survived were already on the aft deck when the ship sank or were lucky to swim clear as she slid below the surface.

All was confusion in the water as people thrashed around in panic trying to find something to keep themselves afloat. Eventually a measure of order was restored and one of the lifeboats, now floating free, was used to rescue as many people as it would hold. A second lifeboat, though damaged, was filled with people and they all made their way to land a few kilometres away.

About one hundred people made it to safety on Little Adolphus Island where they spent an uncomfortable night but they were alive. Captain Sanders was among them. The next morning he set off in the lifeboat manned by some of his men and made for Somerset to report the loss of the ship and get help for those still missing. Apart from the people he had left on the island without food or water, there were many others who had washed up on other islands or were still clinging to pieces of wreckage out in the Strait.

When the news reached authorities on Thursday Island a government steamer was dispatched to search for survivors. Fishing boats from Somerset also combed the waters in the days that followed. In all, about 160 people were saved, many had stories of lucky escapes.

The full story of the Quetta’s loss is told in A Treacherous Coast: Ten Tales of Shipwreck and Survival from Queensland Waters, available as a kindle eBook or paperback through Amazon.

© Copyright C.J. Ison, Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blog posts please enter your email address below.