In July 1833, the colonial cutter Badger left Hobart with its hold filled with supplies intended for Port Arthur. Only this time, as she set off down the Derwent River instead of rounding Cape Raoul and delivering her stores, she kept heading east, past Tasman Island, past Cape Pillar and out to sea. The captain and crew, all convicts still under sentence, had likely been planning their escape for some time. Now they were putting it into action.

The Badger had a crew of four under the command of Captain William Philp. All the men had been mariners before they had run afoul of the law and been banished to Van Diemen’s Land. All but one were serving life sentences, meaning there was no likelihood they would ever return home. Their captain was a former master mariner who had been found guilty of “Wilfully and maliciously destroying the sloop Jane”. Philp had been a part-owner of the vessel as well as its captain. Late one night, he loaded it with gunpowder and blew it up in Penzance Harbour after a falling out with his business partners.

He was tried, found guilty and sentenced to transportation for life. Aged 51, Philp was sent out to Van Diemen’s Land on the convict transport Argyle in 1831. During the passage, he was suspected of conspiring with others to seize the ship and make their escape. The evidence was circumstantial and most likely supplied by a convict informant, but that was enough for Philp and eight or so others to be clapped in chains and separated from the rest of the prisoners. On the Argyle’s arrival in Hobart, the conspirators, including Philp, were tried, found guilty and sentenced to serve hard labour at Macquarie Harbour.

On his eventual return to Hobart, Philp finally got a break. He was put in charge of the 25-ton schooner Badger, ferrying stores from Hobart to Port Arthur about 70 kilometres sailing down the Derwent River. Port Arthur had recently been established to replace Macquarie Harbour, which was about to be shut down the following year.

By 1833, the Badger’s entire crew were experienced seamen. It was not uncommon for the authorities to assign sailors to work on government vessels, for they already had the necessary skills. However, there was always the obvious risk that the colonial administrators were giving them the means of effecting their own escape. Such was the case with the Badger. Governor Arthur was mercilessly criticised for allowing such a situation to eventuate.

On Tuesday, 23 July 1833, William Philp took the Badger out of Sullivan Cove and headed down the Derwent River much as he had done many times before. As well as carrying plenty of provisions, on this trip the Badger was also well equipped with nautical charts, navigation instruments and several muskets recently procured by Philp and his men. What’s more, as many as a dozen convicts had also been smuggled aboard and hidden in the hold.

The Badger left the wharf unchallenged and did not raise any suspicion as she sailed under the guns of Battery Point. To everyone but those on board, she was on her regular passage to Port Arthur. But before she had gone more than five kilometres down the Derwent, she briefly pulled into shore and picked up a final passenger, one George Harding Darby.

Darby, like all the rest of the men on the Badger, was a convict still under sentence. But he enjoyed many privileges not accorded to ordinary convicts sent out to the colonies. A gentleman by birth, he was a member of the same class as the military officers and administrators governing Van Diemen’s Land. At the time, he was employed as a signalman at Mount Nelson Signal Station, which relayed messages from Port Arthur to Hobart. He had also worked at the Water Bailiff’s office and was likely the person who got Philp his job as the Badger’s master and ensured he had a crew of loyal and competent sailors.

Darby and Philp, both nautical men, had become friends while held in a prison hulk awaiting transportation. Darby had come out to Van Diemen’s Land on the William Glen Anderson the same year as Philp had come out on the Argyle. George Darby had served in the Royal Navy and, during Greece’s war of independence from the Ottoman Empire, had commanded a naval vessel under Lord Cochrane. He was also reputed to have served with distinction during the battle of Navarino in 1827 further enhancing his reputation among Hobart’s administrators. However, by 1830, he had left the navy and had found employment as a clerk. By 30 March 1830, he was standing in the docks answering charges of stealing £90 from a fellow gentleman. He was found guilty and sentenced to be transported for life.

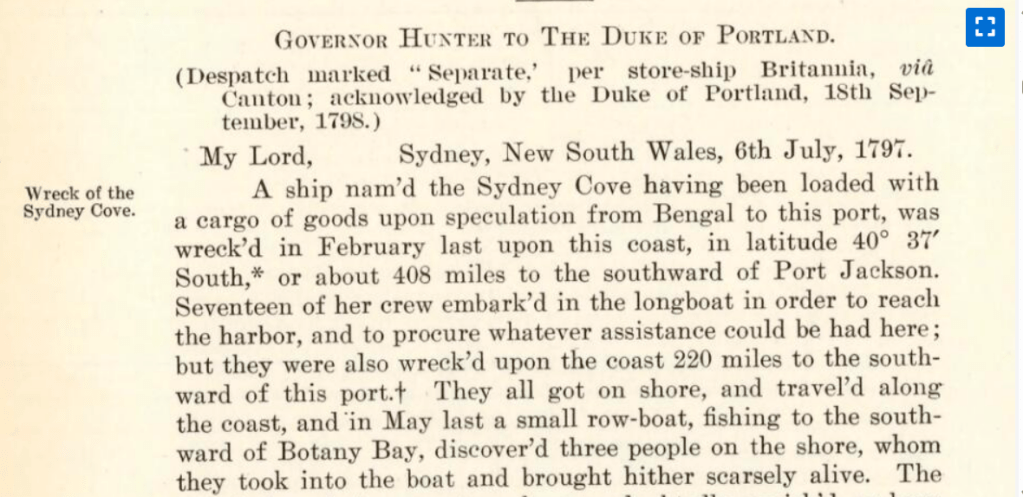

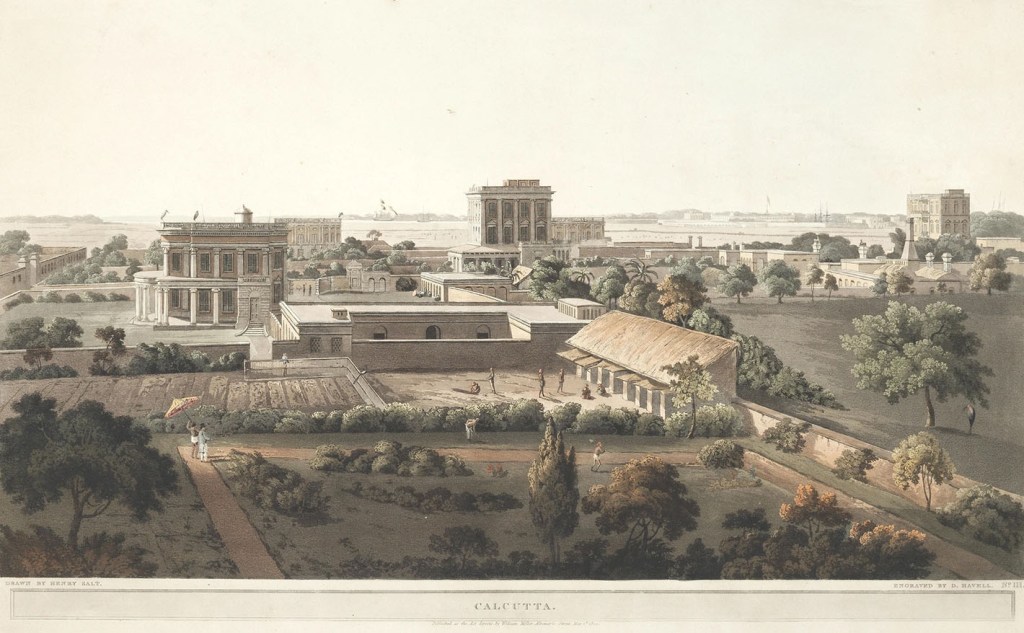

Several days passed before anyone realised the Badger had not delivered her stores to Port Arthur. Boats were sent out to track her down. It was thought that Philp might have sought refuge in the Bay of Islands in New Zealand. So, the brig Isabella was even sent to investigate with a party of soldiers on board. However, she returned to Hobart in late September, having found no trace of the missing Badger. Philp, Darby, and the others had somewhere much further afield in mind when they sailed away from Hobart. They had made their way north, first through the Tasman and from there into the Coral Sea. In September, they pulled into Lifuka in the Friendly Islands (present-day Tonga) before resuming their journey north across the equator and on towards the Philippines.

Philp, Darby and the rest of the runaways eventually arrived in Manila in a longboat, claiming their ship had sunk not far from that port. It is certainly possible that they ran into trouble close to their destination, as they claimed. But it is more likely they had deliberately scuttled the ship rather than risk it being identified as the missing Badger. Philp and Darby would have known that Governor Arthur would have sent a description of the Badger and its runaways far and wide in his effort to track them down.

The bolters did not linger in Manila for very long. They boarded a Spanish ship bound for the Portuguese colony of Macau. But in Macau, their luck nearly ran out. William Philp was spotted by the master of the British merchant ship Mermaid, which happened to be in port. Before taking command of the Mermaid, Captain Stavers had served as the mate on the convict transport Argyle. He immediately recognised Philp as one of the convicts who was suspected of plotting to seize his ship.

Stavers tried to have the Portuguese colonial authorities detain the Philp and his mates. He showed the officials an old copy of the Sydney Herald newspaper, which included a report on the seizure of the Badger as evidence. Philp and Darby were picked up and questioned by a Portuguese official, but they claimed to have never heard of the Badger.

As Philp and the others had kept their noses clean while in Macau, the Governor was not inclined to lock them up on the say-so of a foreigner brandishing an old newspaper in a language he did not understand. Philp and Darby were released to go about their business unmolested, but now that their true identities were known, they thought it was time to move on in. Apparently, most of the runaways had already found berths on an American-flagged ship about to leave port. Philp was last seen in Macau after kindly declining an invitation to join a ship bound for Sydney, telling the British captain, “[he] did not wish to go so far southward.”

Philp, Darby and the rest of the men who fled from Van Diemen’s Land on the Badger are among a very select group of convicts. Of the many hundreds who escaped in stolen or seized vessels, very few are known to have made it to a friendly port. None of the Badger’s men were ever heard of again after leaving Macau.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2024.

Please enter your email address below to be notified of future blogs.