If ever there was a cautionary tale warning of the perils of going to sea ill-prepared, it is that of the tragic loss of the Maria in 1872.

A Marine Board inquiry would blame the captain’s poor navigation and equally poor character for the loss of the ship and so many lives. However, the underlying causes of the disaster dated back to the ship’s purchase and a litany of poorly thought-through decisions made by a committee of young and ambitious men. They had become fixated on seeking adventure and fortune in the wilds of New Guinea and were willing to cut whatever corners necessary to see their plan come to fruition.

In late 1871, the more adventurous sons of some of Sydney’s leading families banded together to travel to New Guinea, where it was said that gold could be found in abundance. Brought up on stories of Australia’s earlier gold rushes, they wanted to leave their mark on the new frontier. They formed a committee and founded the New Guinea Gold Prospecting Association, charging newcomers £10 to go towards the expedition’s costs. Eventually, they signed up 70 men eager to try their luck.

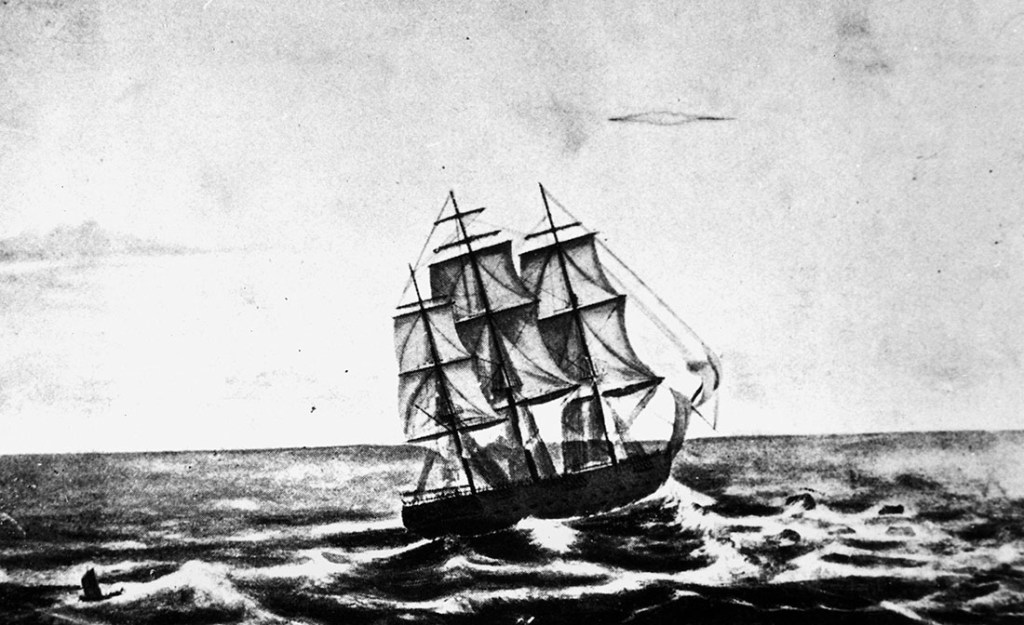

The committee’s first task was to find a ship that would take them to New Guinea so they could prospect for gold in that largely unexplored part of the world. When no one would lease them a ship for the amount of money they could afford, they purchased an aging brig called Maria.

The Maria was over 25 years old, and her glory days were long behind her. She had been seeing out her final days hauling Newcastle coal down the coast to Sydney. Her only redeeming quality was her price. In fact, after a month of searching, she was the only ship they could afford. William Forster, one of the expedition’s survivors, later summed up the state of the vessel thus. “It would, perhaps, have been difficult to find a more unseaworthy old tub anywhere in the southern waters.”

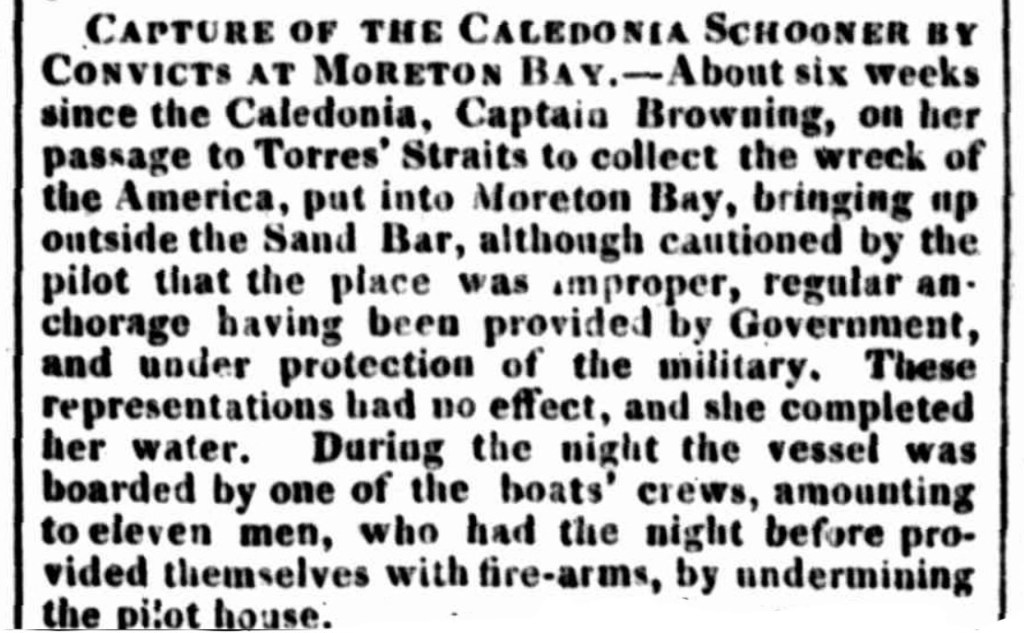

When they were eventually ready to sail the Maria out of Sydney, the port authorities refused them clearance to sail under the Passenger Act because she was overcrowded, unseaworthy, and the passengers, all paid-up members of the prospecting association, were not adequately provided with safety equipment or provisions. Things might have turned out differently had the young men heeded the warning and remedied the shortcomings. But rather than do that, the committee signed on most of the passengers as members of the crew, so the Passenger Act no longer applied.

Alarm bells should have rung out loud and clear when, at the last moment, the captain they had hired refused to take the ship to sea. Feigning illness, it seems he had begun to doubt the wisdom of taking the overcrowded, unseaworthy old tub on a 3700 km passage through the Coral Sea during the North Australian cyclone season.

Then, rather than waste any more time recruiting another qualified master mariner, the committee accepted the first mate’s offer to captain the ship. It was put to a vote, and he was immediately elected to the post with barely a moment’s thought given to whether he was actually up to the task. Though he was officially the Maria’s captain he was more of a sailing master, unable to make decisions without first getting approval from the committee.

The Maria finally sailed out through Sydney Heads on 25 January 1872 with 75 people crammed on board. The first few days passed uneventfully, except for some emerging friction between the prospecting association’s members. They broadly fell into one of two groups: well-heeled, well-educated adventurous young gentlemen from some of the colonies’ leading families, and working-class miners and labourers hoping to make money on the new goldfields. It was probably the first time either group of men had spent time with the other, more or less as equals, and the mix proved volatile at times.

Then, when they were only a few days away from reaching New Guinea, the Maria was caught in a ferocious storm. She was tossed around for five days and sustained serious damage. Water poured through gaps in the deck down into the accommodation, soaking everyone and everything. Her old sails were torn to shreds, rotted rigging snapped under the strain, and a rogue wave tore away a length of the bulwark. They lost all control of the ship for a time after a second rogue wave unshipped the tiller and destroyed the associated steering gear. After one-third of the expedition members signed a petition pleading to be put ashore, the majority voted to turn around and head for Moreton Bay to disembark those who had had enough and make repairs.

But, the badly damaged Maria struggled to make headway against the prevailing southerly trade winds. Captain Stratman decided to make for Cleveland Bay (present-day Townsville) instead. However, he would need to find his way through the Great Barrier Reef guided only by a general coastal chart with a scale of one inch to 50 nautical miles (approx. 1 cm to 40 km). Such a small scale would have provided him with little detail and no doubt less comfort that they would reach Townsville unscathed.

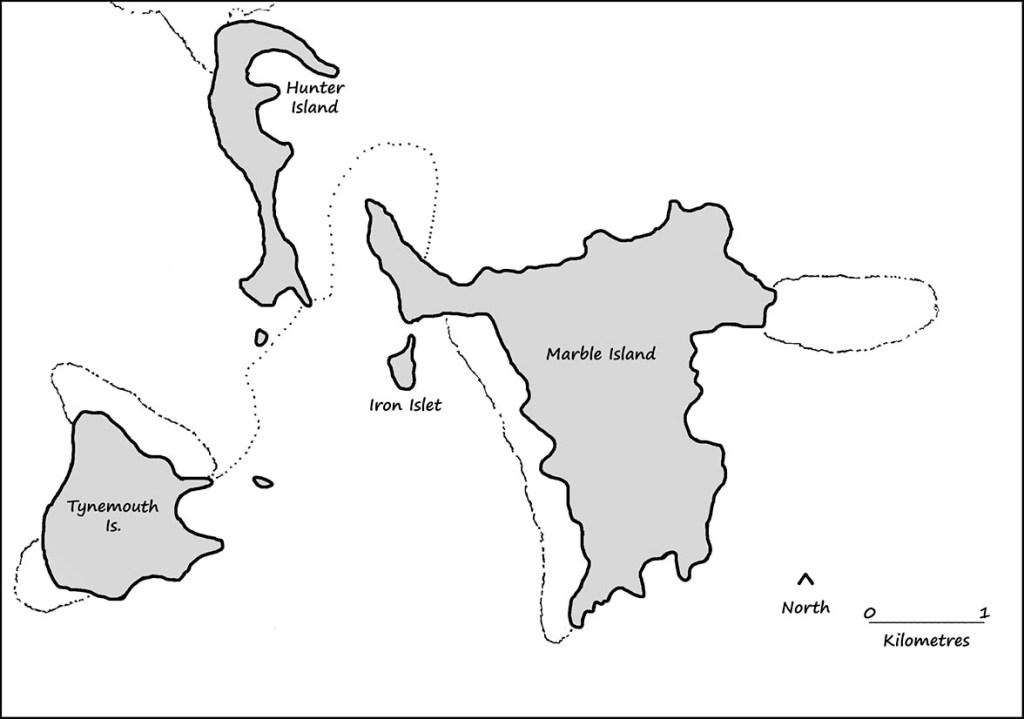

With a lookout stationed high on a mast above, watching for submerged hazards, the Maria gingerly made her way west and soon became entangled in the giant maze of coral reefs and shoals. Thinking they were approaching Magnetic Island and the safety of Cleveland Bay, the captain was unknowingly approaching the coast some 90 km further north. Then, in the early hours of 26 February, their luck finally ran out. The Maria ran onto Bramble Reef off Hinchinbrook Island and began taking on water. A few hours later, she sank to the bottom until just her masts showed above the surface of the water.

Before that happened, Captain Stratman, with a handful of others, had already abandoned the ship in one of their three boats, leaving everyone else to their fate. The class divide separating the expedition members made it almost impossible for anyone to coordinate their efforts. No one would take orders from anyone else. Some eventually made it to Cardwell in the two remaining lifeboats. About a dozen men were last seen clinging to the rigging but they had vanished before rescuers finally found the wreck.

Others had taken to two makeshift rafts, but many of them drowned, and of those who reached land, half were massacred by local Aborigines. Of the 75 people who sailed out of Sydney on the Maria, almost half, 35, lost their lives.

The full story is told in A Treacherous Coast: Ten Tales of Shipwreck and Survival from Queensland Waters available through Amazon.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blog posts, please enter your email address below.