It is an odd piece of Australian history that some of the first people to repeat Captain Cook’s voyage up Australia’s east coast were not other intrepid navigators or explorers, but a motley band of prisoners bent on escape.

In March 1791, nine convicts stole Governor Phillips’ six-oared whaleboat and made their way out through Sydney Heads. That was the start of a 5000 km voyage that would take them up Australia’s east coast, around the tip of Cape York and across the Arafura Sea. On 5 June, after 69 days at sea, they sailed into the Dutch settlement of Kupang on Timor Island. It was a remarkable achievement then, and remains so to this day.

Their leader was a 34-year-old fisherman from Cornwall called William Bryant. He had been sent to New South Wales for impersonating Royal Navy sailors so as to collect their wages. That was back in December 1783. Bryant had been sentenced to transportation for seven years, and by the end of 1790, he had technically completed his sentence and should have been released. However, no one had thought to send the appropriate documentation out with the convicts on the First Fleet, so he had no way to prove his claim. What’s more, the colony was still struggling to feed itself, and Bryant was a valuable man to Governor Phillip and his administration. Bryant kept the colony supplied with fish, even when other sources of sustenance failed.

It seems likely that Bryant had started planning his escape shortly after the seven-year anniversary of his sentence. Even had he been allowed to leave, he probably could not have done so. His wife, Mary, still had a couple of years to serve, and there were two young children to consider. He shared his plans with seven trusted mates, and they began preparations to escape. Those seven were all members of the colony’s fishing fleet, and all had years of maritime experience to draw on.

In the weeks and months leading to their departure, they began stashing away provisions for the long journey. That must have been no easy task, for flour, rice, salted pork, and other staples were all in limited supply. Sydney was starving, and all food was closely monitored and carefully rationed out. However, Bryant was known to have skimmed fish from the catch before handing it over to the Government store. Perhaps he used some of that to trade for the supplies he needed. He also purchased a couple of muskets, a compass, a quadrant and a chart from the captain of a Dutch ship which had recently delivered supplies to Sydney. He likely also paid for these by selling or trading fish on the black market.

On the night of 28 March, they were ready to leave. The Bryants, their two children and the rest of the runaways gathered together everything they had amassed for the voyage and carried it down to Sydney Cove. There, they loaded it into Governor Phillips’ cutter, which happened to be the largest and the sturdiest of the boats in the colony’s small fishing fleet. They then headed across Sydney Harbour and out to sea.

It is hard to imagine what was passing through their minds as they put Sydney behind them. They must have known that the voyage they were embarking on would be fraught with danger. None of them would have been naïve enough to think it would be smooth sailing. They could only rely on their own resourcefulness and a bit of luck to make it to Kupang. On the one hand, remaining in Sydney was hardly a safe alternative. Conditions had grown dire in the struggling colony. Starvation and disease were constant companions. In the previous year alone, 143 people had perished; all but a handful had been convicts.

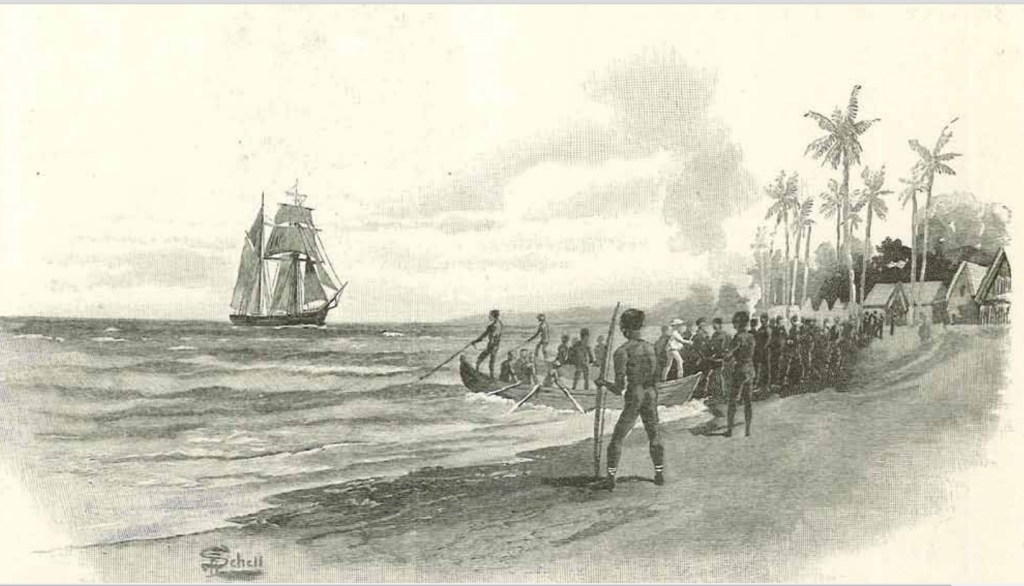

The first place they pulled in to replenish water and look for fresh supplies was the Hunter River. There, they were visited by the local inhabitants, the Awabakal people, and after being given a few gifts, the convicts were left unmolested. However, that would be the only time they received a friendly reception. The next time they pulled in to make repairs to the cutter, they were run off by the local Aborigines. A little while later, they were blown far out to sea, and by the time they had returned to the coast, they found few opportunities to put ashore due to the dangerous surf conditions.

One month after leaving Sydney, they had travelled about 540 nm (1000 km) or only one-fifth of the way to Kupang. This would have placed them somewhere between the Sunshine Coast and Fraser Island (K’gari), where they were forced to land to make urgent repairs to the cutter. It had been taking on water and needed to be recaulked before they continued on their journey north. They were soon heading into Australia’s tropical waters, where they were caught in an unseasonal storm that lashed them for several days without mercy. They were kept bailing continuously to keep afloat, but they survived. They were blown far out into the Coral Sea, and it would take them more than one full day’s sailing west until they found a small deserted island. This was likely Lady Elliot or one of the islands in the Bunker Group a little further north. After weeks of struggle and misfortune, they seized the opportunity to recuperate and escape the cramped conditions on the boat.

The sailing conditions finally improved, and they made steady progress up the Queensland coast, pushed along by the prevailing southerlies. Shortly after rounding Cape York, they replenished their water and then headed out across the Gulf of Carpentaria. It would take them four and a half days to reach East Arnhem Land. Bryant then followed the coastline for several days, looking for a place to refill their water casks. The search proved fruitless, so he decided to head out to sea and make a direct course for Timor. Thirty-six hours later, they made it to Timor Island. It was now 5 June. They had completed their 5000 km voyage in 69 days with no loss of life. That was no mean feat of seamanship and tenacity. Unfortunately, things would soon turn against the runaways.

Bryant and the others passed themselves off as shipwrecked sailors to the Dutch authorities, and for a while, they were treated as such. But then it seems someone blabbed about who they really were, and the Governor locked them in gaol. Shortly after Captain Edwards and his crew arrived in the settlement, genuine survivors of HMS Pandora wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef. When Edwards left for England, Bryant and the rest of the bolters went with him.

William Bryant and his son would die in a Batavia gaol. Three other convicts, plus the Bryants’ daughter, perished on the voyage back to England. Mary Bryant and the four remaining prisoners were put on trial, charged with returning from transportation. They could have been sentenced to death or returned to New South Wales for the rest of their lives. Instead, news of the atrocious conditions in Sydney and their ordeal trying to escape them touched a nerve. They were allowed to serve out their original sentences in England, and by November 1793, Mary Bryant and the four other convicts had all been pardoned and allowed to walk free. A detailed account of the voyage from Sydney to Kupang can be found in “Memorandums” written by James Martin, one of the convicts who made it back to England.

The long and perilous voyage remains one of the great feats of seamanship in an open boat. It is told in more detail in Bolters: An Unruly Bunch of Malcontents.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2022.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.