In April 1875, the pearling schooner John Bull’s crew encountered a man of clearly European descent living with a group of Aborigines on Cape York Peninsula. Mistakenly thinking that the man was being held against his will, they took him on board their vessel and delivered him to the nearest Government outpost at Somerset. His name was Narcisse Pelletier.

Pelletier spent about two weeks at Somerset before being sent to Sydney on the steamer Brisbane. During his time at Somerset, Pelletier had spoken little, but on the voyage south, he was befriended by Lieutenant J.W. Ottley, a British Indian Army officer on leave in Australia. Using his rusty schoolboy French, Ottley coaxed Pelletier to tell him his remarkable story.

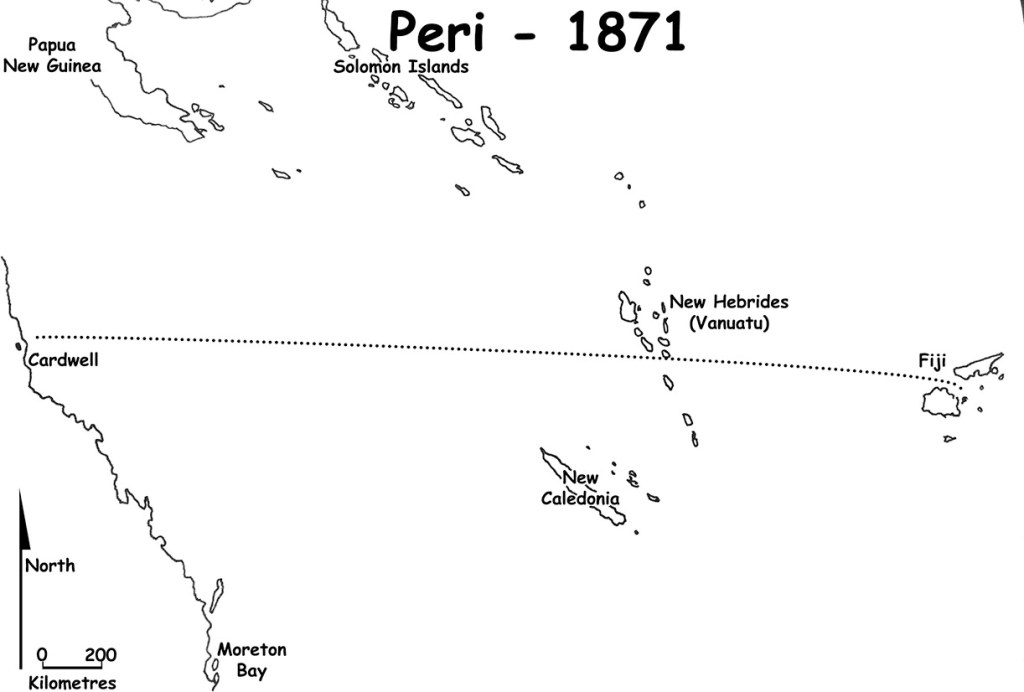

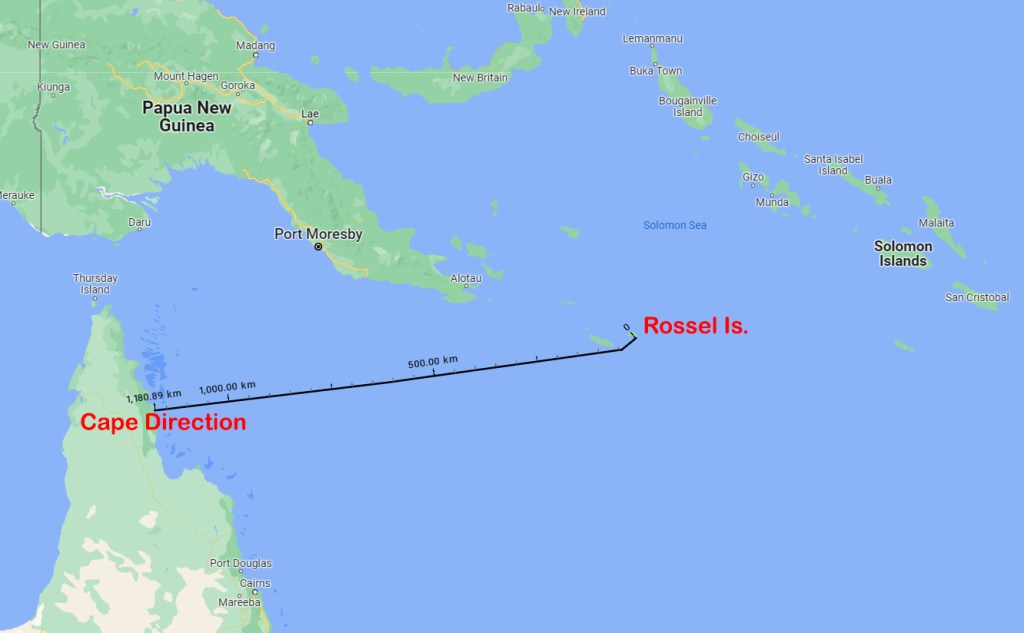

Narcisse Pierre Pelletier was the son of a Saint Gilles shoemaker. At the age of 14, he went to sea as a cabin boy on the Saint Paul under the command of Captain Emmanuel Pinard. The ship sailed from Marseille in August 1857, bound for the Far East. The following year, the Saint Paul left Hong Kong for Sydney with 350 Chinese passengers drawn to New South Wales by the lure of gold. However, the ship was wrecked in the dangerous Louisiade Archipelago off the east coast of New Guinea.

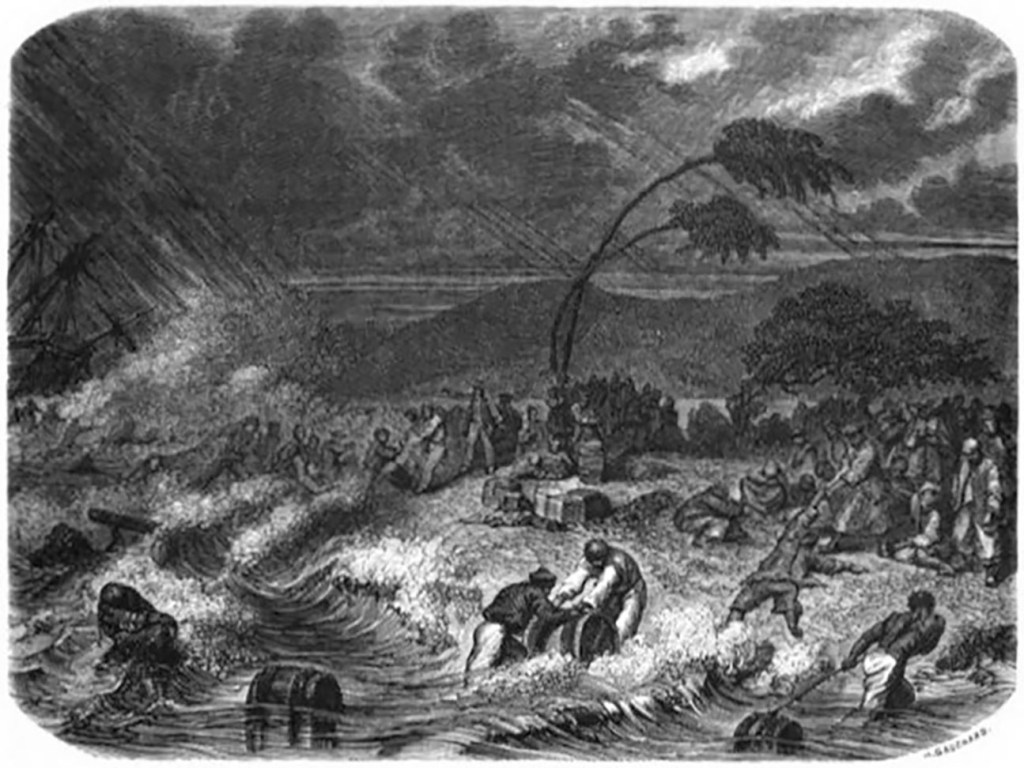

When some of the crew, including Pelletier, went in search of water on Rossel Island, they were attacked by the local inhabitants, and the mate and several sailors were killed. Pelletier himself was struck on the head and barely escaped with his life. He claimed that the captain had then decided their best chance of surviving was for the remaining crew to make for New Caledonia, leaving the Chinese passengers to their fate. This was at odds with Captain Pinard’s own account, in which he claimed to have gone in search of help at the behest of the passengers and that he had left them with most of the provisions and firearms. The story of the shipwreck and the gruesome aftermath is told in the preceding chapter.

Pelletier recalled they suffered greatly in the longboat, surviving on a diet of flour and the raw flesh of a few seabirds that they were able to knock out of the sky when they flew too close to the boat. The sailors’ misery was amplified several days before reaching land when they ran out of drinking water. Pelletier was unsure how long they had been at sea, but they came ashore on the Australian mainland near Cape Direction, the land of the Uutaalnganu people.

Nine of the Saint Paul’s crew reached land, including Captain Pinard and Pelletier. The first water hole they found was so small, according to Pelletier, that by the time everyone else had drunk their fill, there was none left for him. By now, he was half dead from hunger and thirst. He was suffering from exposure to the elements, and his feet had been lacerated from walking barefoot on coral.

He told Ottley that Pinard and the rest of the men had reboarded the boat, intent on reaching the French settlement on New Caledonia, but they set out to sea without him. There he was, abandoned on an alien and possibly hostile stretch of coast far from anything familiar.

Again, Pelletier’s version differs from Pinard’s. The captain claimed that he and all the others had stayed with the Uutaalnganu people for several weeks before they set off and were later picked up by the schooner Prince of Denmark, which eventually took them to New Caledonia. Regardless of the precise circumstances, when his shipmates left, Pelletier remained and was adopted by the Uutaalnganu people.

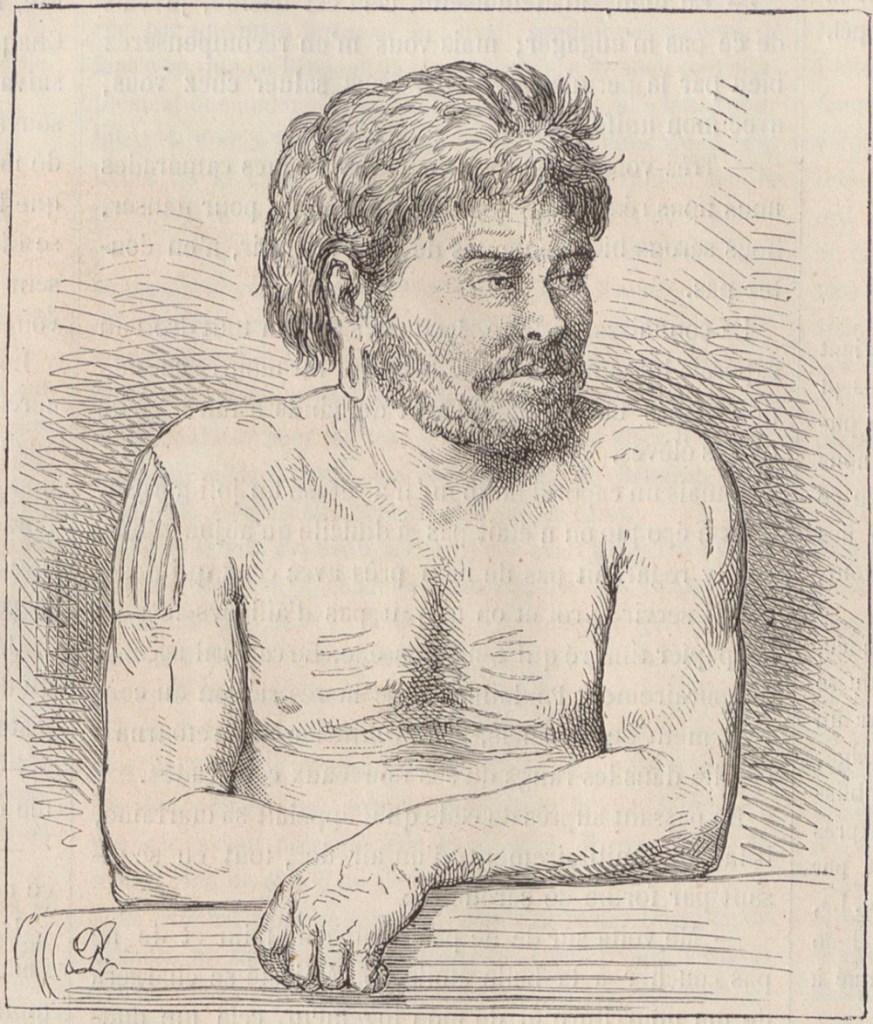

They tended to his injuries and restored him back to good health. Pelletier said that for the first several years, he missed his parents and younger brothers and longed to return home to France. But as time wore on, those feelings faded and were replaced by a strong bond to his Uutaalnganu adopted family. From the ceremonial scars scored on his chest and arms, and the piercing of his earlobe, for which he felt great pride, it is clear he had been initiated into the society. According to a later French biography, Pelletier married an Aboriginal woman and they had several children. He would remain with the Uulaalnganu for 17 years.

Then, in 1875, his world was turned upside down for a second time. One day, the pearling lugger John Bull happened to anchor near Cape Direction. Several sailors came ashore for water and to trade with the Uutaalnganu. They noticed the white man among the local inhabitants and coaxed him to visit their ship. Pelletier told Ottley that he had only gone with them for fear of what the heavily armed sailors might do if he didn’t, rather than any desire to return to “civilisation.” What’s more, he had not expected to be taken away, never to see his family and friends again. Pelletier also confessed to Ottley that he would have preferred being returned to Cape Direction and “his people,” instead of being taken down to Sydney.

Narcisse Pelletier never did return to his Uutaalnganu family. He was delivered to the French Consulate in Sydney, where officials organised passage for him back to France. When, in January 1876, he arrived at his parents’ home, the whole town turned out to greet him. He was given a job as a lighthouse keeper near Saint Nazaire and married for a second time a few years later. Narcisse Pelletier passed away on September 28, 1894, at the age of 50.

© Copyright C.J. Ison / Tales from the Quarterdeck, 2023.

To be notified of future blogs, please enter your email address below.